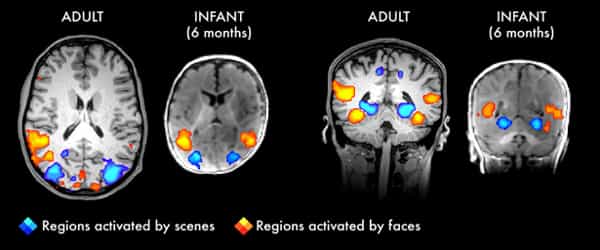

The majority of a baby’s brain development occurs while he or she is sleeping. This is when the connections between their brain’s left and right hemispheres are formed. During sleep, brain synapses are formed: more than 1,000,000 million neural connections are formed per second during their first three years.

A group of researchers discovered that babies twitch during a sleep stage known as quiet sleep, not just REM sleep. The findings may indicate that snoozing infants’ brains and motor systems communicate more than previously thought.

While sleeping, human babies accomplish far more than we previously imagined. A new study from University of Iowa researchers adds to our understanding of the coordination that occurs between infants’ brains and bodies while they sleep.

The Iowa researchers have been studying infants’ twitching movements during REM sleep and how those twitches contribute to babies’ ability to coordinate their bodily movements for many years. The researchers report in this study that beginning around three months of age, infants exhibit a significant increase in twitching during a second major stage of sleep known as quiet sleep.

Human babies do even more than we thought while sleeping. Researchers provide further insights into the coordination that takes place between infants’ brains and bodies as they sleep.

Because a baby learns so much every day, it’s critical that their brain has enough time to process it all. Brain development: Neural connections are vital to your baby’s development. According to research, the REM sleep stage is when neural connections go into overdrive, which means that REM promotes development.

“This was completely unexpected and, for all we know, unique to humans and human infants,” says Mark Blumberg, F. Wendell Miller Professor and Chair of Psychological and Brain Sciences and one of the study’s authors. “Based on our years of observation in baby rats and what’s available in the scientific literature, we were seeing things that we couldn’t explain.”

The researchers recorded the twitches of 22 sleeping infants ranging in age from one week to seven months. Initially, the scientists focused solely on the twitches that occurred alongside REM sleep, consistent with their previous research on REM sleep-associated twitching in other mammals. But then the researchers discovered the infants were twitching their limbs outside of REM sleep as well.

“The twitches looked exactly the same,” says Greta Sokoloff, the study’s lead author and a research scientist in Iowa’s Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. “We didn’t expect to see twitches during quiet sleep; after all, the term “quiet sleep” refers to the fact that humans and other animals don’t move while in that state.

The researchers were able to study brain activity associated with the twitches because they were recording brain waves in sleeping babies. They discovered that during quiet sleep, the infants produced large brain oscillations called sleep spindles about once every 10 seconds, as expected.

Sleep spindles provide insight into the brain’s interaction with its motor system. The researchers discovered that the rate of sleep spindles increased in infant subjects from three to seven months of age and was concentrated along the sensorimotor strip, where the cortex processes sensory and motor information. These sleep spindle facts became especially important after the researchers discovered that the sleep spindles and twitches were synchronized.

Sokoloff says, “Sleep spindles have been widely linked with learning and memory.” “Our findings suggested that the infants were learning about their bodies through twitching during a period of sleep that we previously thought was defined by behavioral silence.”

The discovery opens up a whole new line of inquiry into the brain-body communication that occurs while infants sleep. “Our findings could indicate something significant about cortical contributions to motor control,” Blumberg says. “To get the system set up and working properly, infants must integrate the brain with the body. It is not all linked at birth. After birth, there is a lot of growth that must occur. What we believe we are witnessing is a new model of integration between different parts of the brain and body.”

The study has a small sample size, especially at the younger ages, and the infants were recorded during short periods of daytime sleep, according to the researchers. They intend to recruit more infants and study their sleep patterns during the day and at night in order to confirm the findings. The research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a branch of the National Institutes of Health.