Research from the Oregon State University College of Science demonstrates that songbirds change both their physiology and behavior in response to adjacent birds warning them that food supplies may be running low.

The red crossbills in the study increased their rate of consumption, increased their gut mass, and maintained the size of the muscle responsible for flight when their own eating opportunities were subsequently limited to two brief feeding periods per day after receiving social information from food-restricted neighbors for three days.

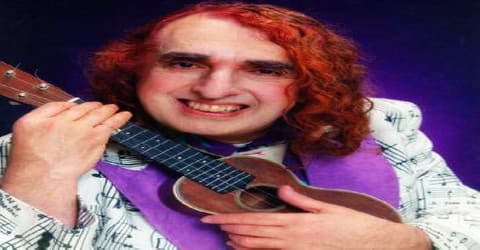

The results of a study conducted by Jamie Cornelius at OSU and published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B journal reveal that birds can use social information about food shortages to their benefit.

“This is an entirely new form of physiological plasticity in birds and builds on prior work showing that social cues during stress can actually change how the brain processes stressors,” said Cornelius, assistant professor of integrative biology.

Ecophysiologist Cornelius studies the coping methods used by wild animals, especially songbirds, to deal with unpredictable and harsh occurrences in their environment, such as changes in food supply. Her work integrates natural history, endocrinology, and biotelemetry to explore the factors that affect an animal’s ability to survive in challenging environments.

“Animals have all kinds of strategies for dealing with challenging environments, ranging from seasonal avoidance strategies like hibernation or migration to behaviors like caching or altered foraging activity,” she said.

“Physiological adjustments in metabolic rate, digestive capacity and energy reserves can sometimes accompany behavioral changes, but those things can take time to execute. That means unpredictable environmental conditions are particularly challenging for many animals.”

In earlier research, Cornelius demonstrated that a red crossbill with a neighbor who is on a restricted diet will secrete higher than usual amounts of the stress hormone corticosterone during its own food-stress periods. The bird will also experience changes in brain activity that will help it respond more forcefully to the challenge.

Crossbills are an interesting study system because of their dependence on conifer seeds. Conifer seed crops are somewhat unpredictable both in where seed crops develop each year and in how long a seed crop might support birds. We use crossbills as a study system to try to understand what strategies birds might have available when food suddenly declines because crossbills may have to cope with this more often than other species.

Jamie Cornelius

The red crossbill, scientifically known as Loxia curvirostra, is a nomadic species that migrates according to the availability of food and takes into account other birds’ cries or behaviors when deciding how to react to a food shortage.

The crossbill is a finch family member that can be found all throughout Europe and North America. It is distinguished by having upper and lower beak tips that cross, as suggested by its common name, a trait that aids in the removal of seeds from pine cones and other fruits.

“Crossbills are an interesting study system because of their dependence on conifer seeds,” Cornelius said. “Conifer seed crops are somewhat unpredictable both in where seed crops develop each year and in how long a seed crop might support birds. We use crossbills as a study system to try to understand what strategies birds might have available when food suddenly declines because crossbills may have to cope with this more often than other species.”

In this study, which used crossbills kept in captivity, some of the birds were exposed to the social information of food-deprived birds for three days before their own food restrictions, while other birds were exposed to the social information of food-deprived birds for three days concurrently with their own food restrictions.

The first group of birds is referred to by Cornelius as the social predictive focal group, and the second group as the social parallel focal group.

“The birds did better at maintaining body mass during food restriction if the social information was predictive of the decline in food resources,” she said. “Social information is important to animals in many different contexts, and this study demonstrates a novel benefit: Advance warning about declining food can lead to better outcomes during times of scarcity.”