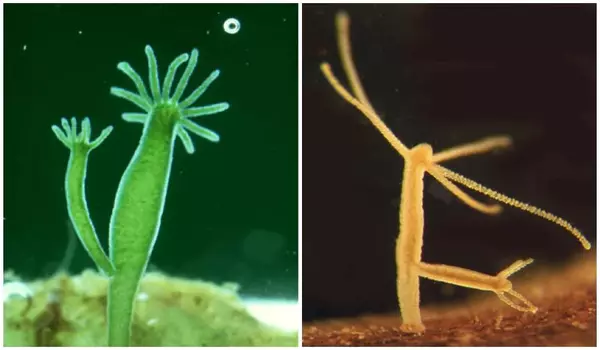

Immortality is the idea of living forever. Some modern species might be biologically immortal. Biological immortality is a state in which the rate of senescence-related mortality is stable or decreasing, decoupling it from chronological age. Various unicellular and multicellular species, including some vertebrates, achieve this state either continuously or after a sufficiently long period of existence. A biologically immortal living being can still die through causes other than senescence, such as injury, poison, disease, a lack of available resources, or environmental changes.

This definition of immortality has been called into question in the Handbook of the Biology of Aging because the increase in mortality rate as a function of chronological age may be negligible at extremely old ages, a concept known as the late-life mortality plateau. In old age, the rate of mortality may stop increasing, but in most cases, the rate is still very high.

Biologists use the term to describe cells that do not have the Hayflick limit on how many times they can divide. This concept is as simple to grasp as it is difficult to put into practice. We are discussing the infinite continuation of human life in its current form, i.e. based on the same biochemical processes in our bodies that keep us alive now. Nature has designed a mechanism for aging and death into our bodies. If we could somehow disable this mechanism, we could theoretically live indefinitely. Our lives are based on metabolism, and the body has the ability to regenerate itself. The process of life could be, in principle, unlimited in time.

Cell lines

Biologists chose the word “immortal” to designate cells that are not subject to the Hayflick limit, the point at which cells can no longer divide due to DNA damage or shortened telomeres. Prior to Leonard Hayflick’s theory, Alexis Carrel hypothesized that all normal somatic cells were immortal.

The term “immortalization” was first used to describe cancer cells that expressed the telomere-lengthening enzyme telomerase and thus avoided apoptosis (cell death caused by intracellular mechanisms). HeLa and Jurkat, both immortalized cancer cell lines, are among the most commonly used cell lines. HeLa cells were derived from a cervical cancer sample taken from Henrietta Lacks in 1951. These cells have been and continue to be widely used in biological research, including the development of polio vaccines, sex hormone steroid research, and cell metabolism. Immortal embryonic stem cells and germ cells have also been described.

Immortal cell lines of cancer cells can be created by induction of oncogenes or loss of tumor suppressor genes. One way to induce immortality is through viral-mediated induction of the large T-antigen, commonly introduced through simian virus 40 (SV-40).

However, it is unclear whether it is possible to modify the form of life of which we are a part in such a way that our bodies become immortal. Contemporary biology has yet to provide a definitive answer to this question. It is possible that the aging mechanism is so deeply embedded that you cannot turn it off without drastically altering the entire machinery of bodily life. And there is still the possibility of an unintentional death, which becomes more serious the longer we live. Another reason to be skeptical of biological immortality. The third reason is that an infinite extension of biological life without some kind of development, evolution, is hardly appealing. Imagine having to live eternally, truly eternally, repeating the same cycle of actions and feelings over and over again. This appears to me to be a nightmare.