Biography of Millicent Fawcett

Millicent Fawcett – British intellectual, political leader, activist, and writer.

Name: Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett

Date of Birth: 11 June 1847

Place of Birth: Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England

Date of Death: 5 August 1929 (aged 82)

Place of Death: Bloomsbury, London, England

Occupation: Suffragist, Union leader

Father: Newson Garrett

Mother: Louise Dunnell

Spouse/Ex: Henry Fawcett (m. 1867)

Children: Philippa Fawcett

Early Life

Millicent Fawcett, leader for 50 years of the movement for woman suffrage in England, was born on 11 June 1847 in Aldeburgh to Newson Garrett, an entrepreneur from Leiston in Suffolk, and his wife, Louisa (née Dunnell; 1813–1903), from London. She was the eighth of ten children. A feminist icon, she is primarily known for her work as a campaigner for women’s suffrage.

From the beginning of her career she had to struggle against almost unanimous male opposition to political rights for women; from 1905 she also had to overcome public hostility to the militant suffragists led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, with whose violent methods Fawcett was not in sympathy. She also was a founder of Newnham College, Cambridge (planned from 1869, established 1871), one of the first English university colleges for women.

A suffragist (rather than a suffragette), Fawcett took a moderate line but was a tireless campaigner. She concentrated much of her energy on the struggle to improve women’s opportunities for higher education, was a governor of Bedford College, London (now Royal Holloway) and in 1875 co-founded Newnham College, Cambridge. She became president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), a position she held from 1897 until 1919. In July 1901 she was appointed to lead the British government’s commission to South Africa investigating conditions in the concentration camps that had been created there in the wake of the Second Boer War. Her report corroborated what the campaigner Emily Hobhouse had said about the terrible conditions in the camps.

Appreciated for her balanced and non-violent ways, she successfully ran the biggest suffrage organization – National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Well-known for her advocacy of women rights, her contribution as a promoter of education and worker welfare has also been well acknowledged. It was only her undying spirit and constitutional means that helped in winning the voting rights for women in Britain. Her writing and oratorical skills are clearly visible in her writings and speeches that she delivered during her long struggle in the arena of women suffrage.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, née Garrett, was born on June 11, 1847, in an upper-middle-class family to Newson Garret and Louise Dunnell in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England. Her father was a ship-owner and a radical politician and had ten children out of which Millicent was seventh.

As a child, Fawcett’s elder sister Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who became Britain’s first female doctor, introduced her to Emily Davies, an English suffragist. In her mother’s biography, Louisa Garrett Anderson quoted Davies saying to her mother, Elizabeth, and to Fawcett: “It is quite clear what has to be done. I must devote myself to securing higher education, while you open the medical profession to women. After these things are done, we must see about getting the vote.” She then turned to Millicent, “You are younger than we are, Millie, so you must attend to that.”

At the age of twelve, Millicent along with her sister was enrolled in a private boarding school in Blackheath, London, from where her inclination towards literature and education began. When she was twelve her sister Elizabeth moved to London to study to qualify as a doctor, and Millicent regularly visited her there. These visits increased her interest in women’s rights.

A key moment occurred when she was 19 and went to hear a speech by the radical MP, John Stuart Mill, an early advocate of universal suffrage. His speech on equal rights for women made a big impression on Millicent, and she became actively involved in his campaign. She was impressed by Mill’s practical support for women’s rights on the basis of utilitarianism, rather than abstract principles. This was the start of Fawcett’s interest in women’s rights. Millicent became an active supporter of Mill’s work.

Personal Life

In April 1867 Millicent married Henry Fawcett, a radical politician, and professor of political economy at Cambridge. She helped him to overcome the handicap of his blindness, while he supported her work for women’s rights, beginning with her first speech on the subject of woman suffrage (1868).

The couple had a daughter in Philippa Fawcett, who later worked as a tutor at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution. She was close to Philippa as they shared skill in needlework; Philippa excelled in school, which fared well with her mother and with women’s rights. Fawcett ran two households, one in Cambridge and one in London. “The Fawcetts were a radical couple, flirting even with republicanism, supporters of proportional representation and trade unionism, keen advocates of individualistic and free trade principles and the advancement of women”. Henry and Millicent’s close relationship was never doubted; they had a real, loving marriage.

Her husband Henry Fawcett passed away in 1884. After his death, she spent her remaining life working for women suffrage.

Career and Works

At the age of 19, Millicent became secretary of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage and J. S. Mill introduced her to many other women’s rights activist.

In 1868 Millicent joined the London Suffrage Committee, and in 1869 she spoke at the first public pro-suffrage meeting to be held in London. In March 1870 she spoke in Brighton, her husband’s constituency, and as a speaker was known for her clear speaking voice. In 1870 she published Political Economy for Beginners, which although short was “wildly successful”, and ran through 10 editions in 41 years. In 1872 she and her husband published Essays and Lectures on Social and Political Subjects, which contained eight essays by Millicent. In 1875 she co-founded Newnham Hall and served on its council.

Her exemplary orating skills helped her political, academic and women issues. The Newnham College in Cambridge was founded by the efforts Millicent Fawcett in 1871. She was also a co-founder of Newnham Hall and served on its Council.

Her first article, on women’s education, appeared in Macmillan’s Magazine in 1868, and her interest in this field led her to become one of the founders of Newnham College for women in Cambridge in 1875. She also published a textbook, Political Economy for Beginners, which went into ten editions and several languages, and also two novels. She campaigned in favor of the enactment of the Married Women’s Property Bill and in favor of the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. The former, in 1882, allowed married women some control over their own finances. The need for this was brought home viscerally to Millicent in 1877 when her purse was stolen at Waterloo Station. The thief was apprehended and charged with ‘stealing from the person of Millicent Fawcett a purse containing £1 18s 6d, the property of Henry Fawcett’. (‘I felt as if I had been charged with theft myself’, she later recalled.) The latter, in 1886, removed the right of police to arrest, detain and medically treat women suspected of being prostitutes, though not of course their male clients an egregious example of the sexual double standard.

After the death of her husband on 6 November 1884, Fawcett temporarily withdrew from public life. She sold both family homes and moved with Philippa into the house of her sister, Agnes Garrett. When she resumed work in 1885, Fawcett began to concentrate on politics and was a key member of what became the Women’s Local Government Society. Originally a Liberal, she joined the Liberal Unionist party in 1886 to oppose Irish Home Rule. In 1904, she resigned from the party on the issue of Free Trade when Joseph Chamberlain gained control in his campaign for Tariff Reform.

A breakthrough came in 1893. Millicent became President of the Special Appeal Committee that was urging suffrage societies to put aside their differences and work together. Finally, in 1897, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was inaugurated, a landmark in the history of the suffrage movement in Britain.

Milicent became president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1897. Finally, in 1918, the Representation of the People Act, which enfranchised about 6,000,000 women, was passed. (Ten years afterward, British women received the vote on a basis of full equality with men.) In 1919 she retired from active leadership of the suffrage union, which had been renamed the National Union for Equal Citizenship.

Under her able leadership, the NUWSS also worked on issues such as slave trading and extending aid for the women and children sufferers in the Boer War. After a lot of hue and cry in the social and political arena, it was only after the First World War that the situation improved. Seeing the active involvement of women in support of war effort, the right to vote for those over 30 was approved by the Qualification of Women Act, 1918.

Millicent Fawcett was granted an honorary LLD by the University of St Andrews in 1899 and was appointed a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) in the 1925 New Year Honours. She died four years later at her home in Gower Street, London. Fawcett was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. Her memory is preserved in the name of the Fawcett Society, and in Millicent Fawcett Hall, constructed in 1929 in Westminster as a place where women could debate and discuss issues that affected them. The hall is owned by Westminster School and is used by its drama department in a 150-seat studio theatre.

Millicent led a moderate campaign for the Women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom and distanced herself from the militant and violent activities of the Pankhursts and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

In July 1901, during the South African War, she was sent by the government to investigate the British concentration camps for Boer civilians. Her report vindicated (whitewashed, in the opinion of some) the administration of the camps. Throughout World War I she dedicated her organization to “sustaining the vital forces of the nation.” After the war, she was made a Dame of the British Empire.

Apart from the suffrage movement, she supported many other causes too. She worked towards curbing child abuse, ending cruelty to children within the family, ending the ‘white slave trade’, preventing child marriage and introduction of regulated prostitution in India. She also campaigned for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which reflected sexual double standards.

Despite the publicity was given to the WSPU, the NUWSS, one of whose slogans was “Law-Abiding suffragists”, retained most support for the women’s movement. By 1905, Fawcett’s NUWSS had 305 constituent societies and almost fifty thousand members. In 1913 they had 50,000 members compared with the WSPU’s 2,000. Fawcett mainly fought for women’s right to vote and found home rule to be “a blow to the greatness and prosperity of England as well as disaster and … misery and pain and shame”. In Fawcett’s book,, Women’s Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement, she explains her disaffiliation with the more militant movement:

I could not support a revolutionary movement, especially as it was ruled autocratically, at first, by a small group of four persons, and latterly by one person only … In 1908, this despotism decreed that the policy of suffering violence, but using none, was to be abandoned. After that, I had no doubt whatever that what was right for me and the NUWSS was to keep strictly to our principle of supporting our movement only by argument, based on common sense and experience and not by personal violence or lawbreaking of any kind.

Millicent wrote ‘Political Economy for Beginners’ (1870, it continued for 10 editions and for 41 years); a novel, ‘Janet Doncaster’ (1875); ‘The Women’s Victory and After’ (1920, about the fight for winning the voting rights) and ‘What I Remember’ (1924).

Millicent believed in ‘grand freemasonry between different classes of women’ and the NUWSS often employed working-class speakers. She was optimistic that the male establishment would be won over. Certainly, a growing number of MPs believed that women, or at least some women, should be allowed to vote. And yet governments failed to take action. A breakthrough seemed to have been made in December 1911, but at the last minute Prime Minister Asquith broke his promise and denied women the vote. ‘If Mr. Asquith desired to revive a violent outbreak of militancy,’ noted Mrs. Fawcett, ‘he could not have … done more to promote his end.’ Her own patience was running thin; that of some women had worn out altogether several years earlier when the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) had been founded.

In the summer of 1913, now aged 66, Millicent took an active part in a mass demonstration which Asquith praised because it was law-abiding. He agreed to see Fawcett’s demonstration, and Milly noted ‘a notable improvement in his attitude and language’; but she had no great hopes of his government. More and more her hopes were on the Labour Party, though it had only 40 seats in the Commons.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the WSPU ceased all of their activities to focus on the war effort and Fawcett’s NUWSS ceased political activity to support hospital services in training camps, Scotland, Russia and Serbia. This was large because the organization was significantly less militant than the WSPU: it contained many more pacifists and support for the war within the organization was weaker. The WSPU was called jingoistic because of its leaders’ strong support for the war. While Fawcett was not a pacifist, she risked dividing the organization if she ordered a halt to the campaign, and diverted NUWSS funds to the government, as the WSPU had done. The NUWSS continued to campaign for the vote during the war and used the situation to their advantage by pointing out the contribution women had made to the war effort.

From May 1916 Mrs. Fawcett urged her members to write to ministers to press for the vote, and she led a delegation to the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, in March 1917. A new franchise bill was being mooted, and she wished to have her say. The result was a new Representation of the People Act, with a female suffrage clause. In March she chaired a rally by the NUWSS in the Queen’s Hall. It was, she said, the greatest moment of her life. It was not a total victory since only women aged 30 and over would be able to vote and thus there would still be fewer women voters than men, who could vote at the age of 21 but it was a great breakthrough. Further reform could only be a matter of time.

In 1910, Fawcett and Dr. Mary Morris were invited to Eagle House near Bath. The house was owned by the Blathwayt family and it featured a garden where the leading suffragettes and suffragists had created an arboretum with a plaque for each notable activist. Fawcett joined dozens of other women who had left commemorative plaques at the house. There was no complaint from the local archaeological society when it was demolished in the 1960s.

In March 1919 Millicent Fawcett, aged almost 72, retired from the presidency of the NUWSS, which now became the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, giving way to the much younger Eleanor Rathbone. But despite her age, Milly retained several influential positions, including being vice-president of the League of Nations Union. She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1925, wrote several more books, and lived to see the 1928 Equal Franchise Act, which gave the vote to all British adults aged 21 and over. At a special celebration, she announced that great things were to be expected of the new emancipated woman.

Awards and Honor

Millicent Fawcett was granted an Honorary LLD by St. Andrew’s University in 1905.

She became Dame Millicent Fawcett in 1924 after getting the Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire.

The Fawcett Library, which is known for its collection on feminism and suffrage movement especially that of Great Britain is named after Millicent Garrett Fawcett.

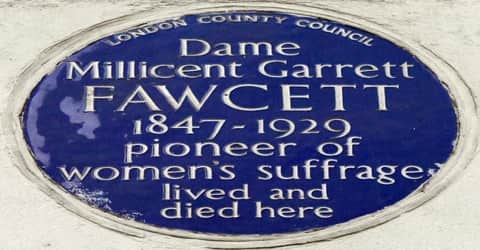

The blue plaque for Fawcett, which states, “Dame Millicent Garrett FAWCETT 1847-1929 pioneer of women’s suffrage lived and died here”, was erected in 1954 by London County Council at 2 Gower Street, Bloomsbury, London WC1E 6DP, London Borough of Camden, where Fawcett lived for 45 years and died.

In February 2018 Fawcett was announced as the winner of the BBC Radio 4 poll for the most influential woman of the past 100 years.

Death and Legacy

Millicent Fawcett died on August 5, 1929, at her home in Gower Street, London. She was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. Her memory is preserved in the name of the Fawcett Society, and in Millicent Fawcett Hall, constructed in 1929 in Westminster as a place where women could debate and discuss issues that affected them. The hall is owned by Westminster School and is used by its drama department in a 150-seat studio theatre.

Fawcett’s writings include Political Economy for Beginners (1870; 9th ed., 1904), a text still in use at her death; Janet Doncaster (1875), a novel; The Women’s Victory and After (1920); and What I Remember (1924).

The Fawcett Society continues to teach British women’s suffrage history to younger generations and inspire young girls and women to continue the fight for gender equality while also creating campaigns like the #FawcettFlatsFriday to make strides in lessening the gender equality gap in Fawcett’s name.

The Fawcett archives are held at The Women’s Library at the Library of the London School of Economics, ref 7MGF.

Her memories are preserved in the form of Fawcett Society and Millicent Fawcett Hall, constructed in 1929 in Westminster as a place to discuss women issues. It is now under the drama department of the Westminster School as a 150 seat studio theatre.

Millicent Fawcett’s story lacks the drama of Emmeline Pankhurst’s. She never went to prison and never really suffered for the cause. She was too much the well-rounded individual and had too much faith in reason and democracy ever to be an unbalanced extremist. Admittedly she seems today a somewhat remote figure. Very much a Victorian liberal, she idealized the family, opposed birth control and stood for personal responsibility, so that she opposed free education and, later, family allowances. She was deeply offended by the Edwardian advocates of free love. When presented with a copy of the Freewoman, she found it ‘objectionable and mischievous’ and ripped it into little pieces. Yet she worked long and hard to bring about votes for women. There are different types of heroism, and to give decades of her life to the cause, and to do so patiently and moderately, without giving way to hate or despair, surely qualifies Millicent Fawcett as a heroine whose praises should be a song more loudly than they are.

Information Source: