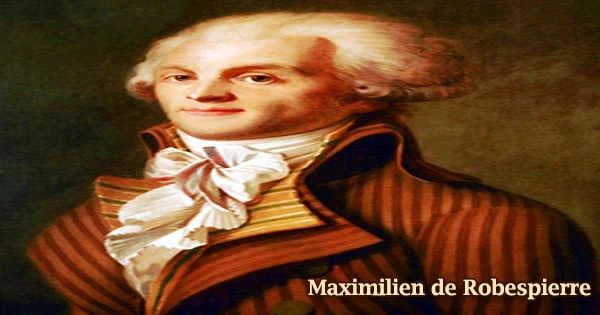

Full name: Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre

Date of birth: 6 May 1758

Place of birth: Arras, Artois, France

Date of death: 28 July 1794 (aged 36)

Place of death: Place de la Révolution, Paris, France

Occupation: Lawyer and Politician

Political party: The Mountain (1792–1794); Jacobin Club (1789–1794)

Father: François Maximilien Barthélémy de Robespierre

Mother: Jacqueline Marguerite Carrault

Early Life

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (French: mak.si.mi.ljɛ̃ ʁɔ.bɛs.pjɛʁ), a French lawyer who became one of the most important figures of the French Revolution, was born on May 6, 1758, and died on July 28, 1794. Either a despot or a man of the people, Robespierre was either the Revolution’s savior or the embodiment of evil. However, the reality is a little bit more nuanced than many historical personalities would have us believe. He was a significant figure in French politics of the 18th century and a member of the Committee of Public Safety, which he presided over in the latter months of 1793.

He advocated for universal manhood suffrage, the elimination of both clerical celibacy and slavery while serving as a member of the Estates-General, the Constituent Assembly, and the Jacobin Club. Robespierre was born and raised in Arras (a ‘ras), which is about 100 miles north of Paris. He was raised as a lawyer’s son, went on to practice law, and made a name for himself as a local official. He had a reputation for being kind, standing up for the underprivileged in court, which made the local nobility suspicious of him.

After being chosen as the “public accuser” in 1791, Robespierre became a vocal supporter of male citizens without political representation, their unrestricted admission to the National Guard, to positions of public trust, and to the commissioned ranks of the army, as well as their rights to petition and to keep and bear arms for self-defense. His protestations in his “Mémoire pour le Sieur Dupond” (“Report for Lord Dupond”) against royal absolutism and arbitrary justice had disturbed the upper classes as a lawyer for the underprivileged.

He entered politics and over time rose to the position of president of the influential Jacobin political movement. He opposed monarchy and was a key figure in the rebellion against King Louis XVI in August 1792, which led to the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French Republic. Although Robespierre always had allies who shared his views, others were turned off by the political violence that the Montagne faction frequently supported.

In addition, the anticlericals and other political forces mistrusted him because of the deist Cult of the Supreme Being he formed and zealously supported because they thought he had grandiose illusions about his standing in French society.

Robespierre was a revolutionary at heart, and although he had previously advocated the death penalty, he soon started ruthlessly purging individuals he regarded as the movement’s foes. Due to his autocratic rule, he lost support and was eventually captured and killed in July 1794.

Childhood and Educational Life

Maximilien de Robespierre was born in Arras in the old French province of Artois on 6th May 1758. His father, François Maximilien Barthélémy de Robespierre, was a lawyer at the Conseil d’Artois, and his mother Jacqueline Marguerite Carrault, was the daughter of a brewer. Maximilien was the eldest of the couple’s four children. He lost his mother when he was just six years old.

Unable to cope with the loss of his wife, his father abandoned the children who were then brought up by their paternal aunts Eulalie and Henriette de Robespierre. Already literate at age eight, Maximilien started attending the collège of Arras (middle school). In October 1769, on the recommendation of the bishop fr:Louis-Hilaire de Conzié, he received a scholarship at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris. His fellow pupils included Camille Desmoulins and Stanislas Fréron.

He was profoundly affected by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas as a student and took on many of his tenets. He received the top rhetoric prize in 1776. He also appreciated the language of the classical writers Cato, Cicero, and others. Additionally, he read the writings of Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and was drawn to many of the concepts expressed in his Contrat Social.

After earning his legal degree in 1781, Robespierre settled down in Arras to practice law alongside his sister Charlotte. He gained notoriety quickly and was named a judge in the Salle Épiscopale, a court with authority over the diocese’s provostship.

Personal Life

Maximilien Robespierre remained a bachelor throughout his life.

Working and Political Career

After being accepted into the Arras Academy in 1783, Maximilien Robespierre quickly rose to the position of chancellor and eventually president. Contrary to long-held assumptions that Robespierre lived a solitary existence, he frequently visited prominent locals and interacted with the neighborhood’s youth. He became a man of letters when the Academy of Metz honored him with a medal in 1784 for his article on the topic of whether a condemned criminal’s family should also share in his shame. He split the award with journalist and advocate Pierre Louis de Lacretelle from Paris.

By 1788 Robespierre was already well known for his altruism. As a lawyer representing poor people, he had alarmed the privileged classes by his protests in his “Mémoire pour le Sieur Dupond” (“Report for Lord Dupond”) against royal absolutism and arbitrary justice. In April 1789, he was elected leader of the significant Jacobin political movement. He contributed to the creation of the French constitution’s founding document, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the year after.

Robespierre was a member of the Jacobin Club, also known as the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution. The Friends of Civic Participation, who supported the changes in France, welcomed non-deputies to the Club Breton after the National Assembly moved to Paris into a former and vacant abbey. Originally, this group (the Club Breton) solely consisted of deputies from Brittany.

Robespierre was closely associated with the Jacobins, a left-leaning political group that met in an old Catholic monastery and went by that name in 1790. The Jacobins, together with their allies, occupied a high seat on the left side of the National Assembly and behaved somewhat like a political party or a radical pressure group. The name “montagnards” or “the Mountain” soon became associated with Robespierre and his allies.

In September 1791, Robespierre backed the reunification of Avignon, once a papal province, with France and stood up for performers, Jews, and Black enslaved people. In order for the upcoming legislature, which would be a brand-new assembly, to better embody the will of the people, he had successfully suggested in May that all new deputies be chosen.

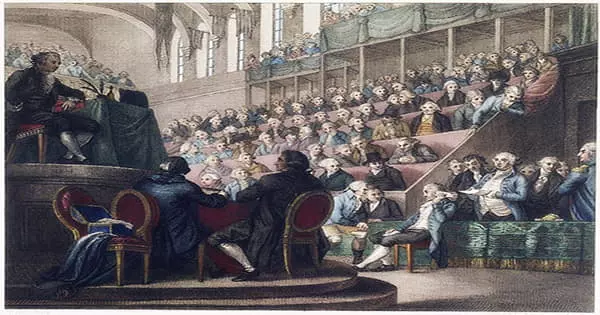

King Louis attempted to depart the kingdom in 1791 with his family, but it was later revealed that they had been scheming with France’s enemies abroad. Robespierre successfully campaigned for the King’s execution in 1792, following the start of the war with Austria and the so-called Second Revolution. On September 21, 1792, the Convention, under his direction, formally abolished the monarchy and proclaimed France a republic. Robespierre advocated in favor of the king’s execution, which took place in January 1793 after the king was found guilty of treason and put on trial.

When Brissot’s supporters stirred up opinion against him, Robespierre founded a newspaper, Le Défenseur de la Constitution (“Defense of the Constitution”), which strengthened his hand. He attacked Lafayette, who had become the commander of the French army and whom he suspected of wanting to set up a military dictatorship, but failed to obtain his dismissal and arrest.

Robespierre’s power expanded when the king was put to death. However, France’s problems also grew worse, and a state government became necessary. In March 1793, the Jacobins established a Revolutionary Tribunal and Robespierre was a member of the Committee of Public Safety, which took the place of the Committee of General Defense.

He soon rose to the top of the committee that instigated the “Reign of Terror” in September 1793 to address the country’s escalating unrest and the possibility of foreign invasion. Tens of thousands of “enemies of the revolution” were mass-murdered during this time period, which was characterized by tremendous violence. After the murders, Robespierre gained a bad reputation.

The Hébertists, the Cordeliers, and the popular militants all called for more-radical measures and encouraged de-Christianization and the prosecution of food hoarders. Their excesses frightened the peasants, who could not have been pleased by the decrees of 8 and 13 Ventôse, year II (February 26 and March 3, 1794), which provided for the distribution among the poor of the property of suspects.

The Thermidorian Reaction, a coup d’état against the Jacobin Club leaders who had control of the Committee of Public Safety, was a result of the tremendous violence unleashed during the Reign of Terror. Robespierre, along with several other people who had played significant roles in the Reign of Horror, was arrested after being charged with being the inspiration for the terror. The guillotine was used to shave the necks of aristocrats, disobedient priests, monarchist politicians, unsuccessful generals, and anyone who was deemed to be either too moderate or insufficiently extreme.

Desmoulins, a journalist and a friend of Robespierre, said of this time: “The gods are thirsty.” An estimated 40,000 people had died by the summer of 1794. On June 4th, Robespierre was chosen to preside over the National Convention, but his excessive power alarmed both supporters and foes. Since the start of the session, Robespierre has given roughly 450 speeches in the Legislative Assembly and at the Jacobin Club. His health has suffered as a result, and he has grown agitated and distant.

Even though Robespierre was well-received that evening at the Jacobin Club, his opponents were successful in keeping him from testifying before the Convention the next day after it had accused him along with his brother Augustin and three of his colleagues. Robespierre was brought to the prison in Luxembourg, but the warden declined to imprison him.

Death and Legacy

The National Convention declared Robespierre an outlaw after he shot himself in the jaw with a gun in the Hôtel de Ville, confusing his supporters and seriously injuring himself. Attacking the Hôtel de Ville, the National Convention soldiers quickly captured Robespierre and his supporters. He was executed on 28 July 1794 along with several of his close aides. His death ended the most radical phase of the French Revolution.

Most people associate Maximilien Robespierre with the Reign of Terror, a time of slaughter and terror that occurred at the start of the French Revolution. As a member of the Revolutionary Tribunal and the Committee of Public Safety, Robespierre murdered several “enemies of the revolution,” which made him very unpopular and ultimately contributed to his downfall.