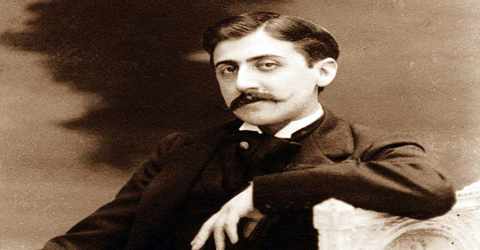

Biography of Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust – French novelist, critic, and essayist.

Name: Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust

Date of Birth: 10 July 1871

Place of Birth: Auteuil, France

Date of Death: 18 November 1922 (aged 51)

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Novelist, essayist, critic

Father: Achille Adrien Proust

Mother: Jeanne Clémence Weil

Early Life

French novelist Marcel Proust was one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century and he was born in the Paris Borough of Auteuil (the south-western sector of the then-rustic 16th arrondissement) at the home of his great-uncle on 10 July 1871, two months after the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ended the Franco-Prussian War. He was a French novelist, critic, and essayist best known for his monumental novel À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time; earlier rendered as Remembrance of Things Past), published in seven parts between 1913 and 1927. He is considered by critics and writers to be one of the most influential authors of the 20th century.

This twentieth-century novelist was known to have as much impact on literature, as Tolstoy had during the nineteenth century. His writing was so compelling and impressive that even the great English writer Virginia Woolf once exclaimed: “Oh if I could write like that!”. Born during the Fourth French Revolution, Proust grew up witnessing a lot of turmoil in the society. His magnum opus ‘In Search of Lost Time’, which earned him great fame and recognition, describes the society plagued by chaos and absurdities brought about by industrialization. The beautiful and the awe-inspiring nature, which had been the subject and the muse of poets and writers of the previous ages, began to fade with the beginning of industrialization. But, Proust was among those few people who found inspiration to write, despite all the cynicism.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (/pruːst/; French: maʁsɛl pʁust), known as Marcel Proust, was born July 10, 1871, Auteuil, near Paris, France. He was born during the violence that surrounded the suppression of the Paris Commune, and his childhood corresponded with the consolidation of the French Third Republic. Much of In Search of Lost Time concerns the vast changes, most particularly the decline of the aristocracy and the rise of the middle classes, that occurred in France during the Third Republic and the fin de siècle. After the first attack in 1880, he suffered from asthma throughout his life.

His parents, Dr. Adrien Proust and Jeanne Weil, were wealthy. Proust was a nervous and frail child. When he was nine years old, his first attack of asthma (a breathing disorder) nearly killed him. Proust was raised in his father’s Catholic faith.s He was baptized (on 5 August 1871, at the church of Saint-Louis d’Antin) and later confirmed as a Catholic, but he never formally practiced that faith. He later became an atheist and was something of a mystic.

In 1882 Proust enrolled in the Lycée Condorcet. Only during his last two years of study there did he distinguish himself as a student. After a year of military service, Proust studied law and then philosophy (the study of the world and man’s place in it). Proust became known as a brilliant conversationalist with the ability to mimic others, although some considered him a snob and social climber.

Proust had a close relationship with his mother. To appease his father, who insisted that he pursue a career, Proust obtained a volunteer position at Bibliothèque Mazarine in the summer of 1896. After exerting considerable effort, he obtained a sick leave that extended for several years until he was considered to have resigned. He never worked at his job, and he did not move from his parents’ apartment until after both were dead.

Personal Life

Marcel Proust is believed to have been homosexual, and his sexuality and relationships with men are often discussed by his biographers. Although his housekeeper, Céleste Albaret, denies this aspect of Proust’s sexuality in her memoirs, her denial runs contrary to the statements of many of Proust’s friends and contemporaries, including his fellow writer André Gide as well as his valet Ernest A. Forssgren. He was never married.

He was one of the first European novelists to write on the subject of homosexuality. Proust never openly admitted to his homosexuality, though his family and close friends either knew or suspected it. In 1897, he even fought a duel with writer Jean Lorrain, who publicly questioned the nature of Proust’s relationship with Lucien Daudet (both duelists survived). Despite Proust’s own public denial, his romantic relationship with composer Reynaldo Hahn, and his infatuation with his chauffeur and secretary, Alfred Agostinelli, are well documented.

However, In Search of Lost Time discusses homosexuality at length and features several principal characters, both men and women, who are either homosexual or bisexual: the Baron de Charlus, Robert de Saint-Loup, and Albertine Simonet. Homosexuality also appears as a theme in Les plaisirs et Les jours and his unfinished novel, Jean Santeuil.

Career and Works

Marcel Proust served in the French army from 1889 to 1890, during which he was stationed at the Coligny Barracks in Orléans. From 1890 to 1891, he contributed columns to the journal ‘Le Mensuel’. He was also one of the founding members of the literary periodical called ‘Le Banquet’ in which he published a number of articles.

His first work, Les Plaisirs et Les Jours (Pleasures and Days), a collection of short stories and short verse descriptions of artists and musicians, was published in 1896. Proust had made an attempt at a major work in 1895, but he was unsure of himself and abandoned it in 1899. It appeared in 1952 under the title of Jean Santeuil; from thousands of pages, Bernard de Fallois had organized the novel according to a sketchy plan he found among them. Parts of the novel make little sense, and many passages are from Proust’s other works. Some, however, are beautifully written. Jean Santeuil is the biography of a made-up character who struggles to follow his artistic calling.

Proust’s discovery of John Ruskin’s art criticism in 1899 caused him to abandon Jean Santeuil and to seek a new revelation in the beauty of nature and in Gothic architecture, considered as symbols of man confronted with eternity: “Suddenly,” he wrote, “the universe regained in my eyes an immeasurable value.” On this quest, he visited Venice (with his mother in May 1900) and the churches of France and translated Ruskin’s Bible of Amiens and Sesame and Lilies, with prefaces in which the note of his mature prose is first heard.

Beginning in 1895 Marcel Proust spent several years reading Carlyle, Emerson, and John Ruskin. Through this reading, he refined his theories of art and the role of the artist in society. Also, in Time Regained Proust’s universal protagonist recalls having translated Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies. The artist’s responsibility is to confront the appearance of nature, deduce its essence and retell or explain that essence in the work of art. Ruskin’s view of artistic production was central to this conception, and Ruskin’s work was so important to Proust that he claimed to know “by heart” several of Ruskin’s books, including The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Bible of Amiens, and Praeterita.

In 1903 Proust’s father died. The death of his mother two years later forced Proust into a sanatorium (an institution for rest and recovery), but he stayed less than two months. He emerged once again into society and into print after two years with a series of articles published in Le Figaro during 1907 and 1908.

Marcel Proust inherited much of his mother’s political outlook, which was supportive of the French Third Republic and near the liberal center of French politics. In an 1892 article published in Le Banquet entitled “L’Irréligion d’État”, Proust condemned extreme anti-clerical measures such as the expulsion of monks, observing that “one might just be surprised that the negation of religion should bring in its wake the same fanaticism, intolerance, and persecution as religion itself.” He argued that socialism posed a greater threat to society than the Church. Reflecting on the subject again in 1904, in the article “La Mort des cathédrales”, Proust wrote that his fears over the fate of the French culture had subsided as anti-clerical deputies allied with the clergy when faced with German aggression. Proust always rejected the bigoted and illiberal views harbored by many priests at the time, but believed that the most enlightened clerics could be just as progressive as the most enlightened secularists and that both could serve the cause of “the advanced liberal Republic.”

The year 1908 proved beneficial for him as he began writing satires on the works by other writers, all of which were published in the daily newspaper ‘Le Figaro’. These writings rendered him the confidence to expand the horizon of his works. Thus, he began writing essays, articles and short stories, eventually merging and developing them into a single novel.

By November 1908 Proust was planning his Contre Sainte-Beuve (published in 1954; On Art and Literature). He finished it during the summer of 1909 and immediately started work on his great novel.

In January 1909 occurred the real-life incident of an involuntary revival of a childhood memory through the taste of tea and a rusk biscuit (which in his novel became madeleine cake); in May the characters of his novel invaded his essay; and in July of this crucial year he began À la recherche du temps perdu. He thought of marrying “a very young and delightful girl” whom he met at Cabourg, a seaside resort in Normandy that became the Balbec of his novel, where he spent summer holidays from 1907 to 1914, but, instead, he retired from the world to write his novel, finishing the first draft in September 1912.

Begun in 1909, when Proust was 38 years old, À la recherche du temps perdu consists of seven volumes totaling around 3,200 pages (about 4,300 in The Modern Library’s translation) and featuring more than 2,000 characters. Graham Greene called Proust the “greatest novelist of the 20th century”, and W. Somerset Maugham called the novel the “greatest fiction to date”. André Gide was initially not so taken with his work. The first volume was refused by the publisher Gallimard on Gide’s advice. He later wrote to Proust apologizing for his part in the refusal and calling it one of the most serious mistakes of his life.

In 1913 Proust found a publisher who would produce, at the author’s expense, the first of three projected volumes Du Côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way). French writer André Gide (1869–1951) in 1916 obtained the rights to publish the rest of the volumes. À l’ombre des Jeunes Filles en fleur (Within a Budding Grove), originally a chapter title, appeared in 1918 as the second volume and won the Goncourt Prize. As other volumes appeared, Proust expanded his material, adding long sections just before publication. Feeling his end approaching, Proust finished drafting his novel and began revising and correcting proofs.

In December 1919, through Léon Daudet’s recommendation, À l’ombre received the Prix Goncourt, and Proust suddenly became world famous. Three more installments appeared in his lifetime, with the benefit of his final revision, comprising Le Côté de Guermantes (1920–21; The Guermantes Way) and Sodome et Gomorrhe (1921–22; Sodom and Gomorrah).

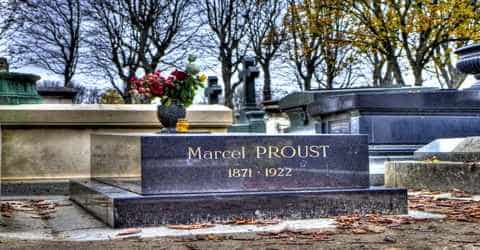

Death and Legacy

The writer was deeply affected by the death of his mother in September 1905. After the death of his mother, Proust’s health began to deteriorate and he spent the last three years of his life in his cork-lined bedroom.

On November 18, 1922, Proust died of bronchitis and pneumonia (diseases of the lungs) contracted after a series of asthma attacks. The final volumes of his novel appeared under the direction of his brother Robert.

Marcel Proust’s novel has a circular construction and must be considered in the light of the revelation with which it ends. The author reinstates the extratemporal values of time regained, his subject being salvation. Other patterns of redemption are shown in counterpoint to the main theme: the narrator’s parents are saved by their natural goodness, great artists (the novelist Bergotte, the painter Elstir, the composer Vinteuil) through the vision of their art, Swann through suffering in love, and even Charlus through the Lear-like grandeur of his fall. Proust’s novel is, ultimately, both optimistic and set in the context of human religious experience.

His masterpiece ‘À la recherche du temps perdu’, translated as ‘In Search of Lost Time’ in English, was called the “greatest novel of the 20th century” by Graham Greene, and “greatest fiction to date” by W. Somerset Maugham.

Taking as raw material the author’s past life, À la recherche is ostensibly about the irrecoverability of time lost, about the forfeiture of innocence through experience, the emptiness of love and friendship, the vanity of human endeavour, and the triumph of sin and despair; but Proust’s conclusion is that the life of every day is supremely important, full of moral joy and beauty, which, though they may be lost through faults inherent in human nature, are indestructible and recoverable. Proust’s style is one of the most original in all literature and is unique in its union of speed and protraction, precision and iridescence, force and enchantment, classicism and symbolism.

Information Source: