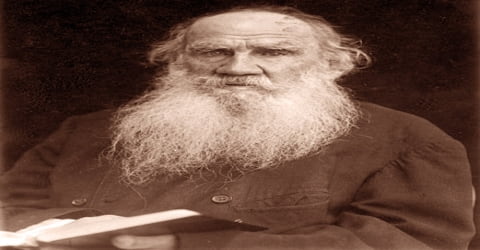

Biography of Leo Tolstoy

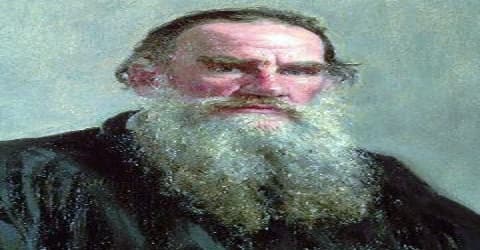

Leo Tolstoy – Russian writer.

Name: Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Date of Birth: September 9, 1828

Place of Birth: Yasnaya Polyana, Tula Governorate, Russian Empire

Date of Death: November 20, 1910 (aged 82)

Place of Death: Astapovo, Ryazan Governorate, Russian Empire

Occupation: Novelist, short story writer, playwright, essayist

Father: Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy

Mother: Countess Mariya Tolstaya

Spouse: Sophia Behrs (m. 1862)

Early Life

Leo Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, his family’s estate, on August 28, 1828, in Russia’s Tula Province, the youngest of four sons. He was a Russian author, a master of realistic fiction and one of the world’s greatest novelists.

Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828, he is best known for the novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), often cited as pinnacles of realist fiction. He first achieved literary acclaim in his twenties with his semi-autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth (1852–1856), and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), based upon his experiences in the Crimean War. Tolstoy’s fiction includes dozens of short stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Family Happiness (1859), and Hadji Murad (1912). He also wrote plays and numerous philosophical essays.

In the 1860s, he wrote his first great novel, War and Peace. In 1873, Tolstoy set to work on the second of his best-known novels, Anna Karenina. He continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s. One of his most successful later works was The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

In the 1870s Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work A Confession (1882). His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist. Tolstoy’s ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894), were to have a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Tolstoy also became a dedicated advocate of Georgism, the economic philosophy of Henry George, which he incorporated into his writing, particularly Resurrection (1899).

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Leo Tolstoy, Tolstoy also spelled Tolstoi, Russian in full Lev Nikolayevich, Graf (count) Tolstoy, was born on August 28, 1828, at Yasnaya Polyana, a family estate 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, Russia, and 200 kilometers (120 mi) south of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), a veteran of the Patriotic War of 1812, and Countess Mariya Tolstaya (née Volkonskaya; 1790–1830). His mother died when he was two years old, whereupon his father’s distant cousin Tatyana Ergolsky took charge of the children. In 1837 Tolstoy’s father died, and an aunt, Alexandra Osten-Saken, became a legal guardian of the children. Her religious dedication was an important early influence on Tolstoy. When she died in 1840, the children were sent to Kazan, Russia, to another sister of their father, Pelageya Yushkov.

Tolstoy was educated at home by German and French tutors. He was not a particularly exceptional student but he was good at games. In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages at Kazan University. His time there was not a success, however, with teachers describing him as “both unable and unwilling to learn.”

Planning on a diplomatic career, he entered the faculty of Oriental languages. Finding these studies too demanding, he switched two years later to studying law. Tolstoy left the university in the middle of his studies, returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much of his time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle. He began writing during this period, including his first novel Childhood, a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.

Nikolay, Tolstoy’s eldest brother, visited him at in 1848 in Yasnaya Polyana while on leave from military service in the Caucasus. Leo greatly loved his brother, and when he asked him to join him in the south, Tolstoy agreed. After a long journey, he reached the mountains of the Caucasus, where he sought to join the army as a Junker, or gentleman-volunteer. Tolstoy’s habits on a lonely outpost consisted of hunting, drinking, sleeping, chasing the women, and occasionally fighting. During the long lulls, he first began to write.

Personal Life

The death of his brother Nikolay in 1860 had an impact on Tolstoy and led him to a desire to marry. On September 23, 1862, Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was 16 years his junior and the daughter of a court physician. She was called Sonya, the Russian diminutive of Sofia, by her family and friends. They had 13 children.

Career and Works

Tolstoy is considered one of the giants of Russian literature; his works include the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina and novellas such as Hadji Murad and The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

During quiet periods while Tolstoy was a junker in the Army, he worked on an autobiographical story called Childhood. In it, he wrote of his fondest childhood memories. In 1852, Tolstoy submitted the sketch to The Contemporary, the most popular journal of the time. The story was eagerly accepted and became Tolstoy’s very first published work.

During the next few years Tolstoy published a number of stories based on his experiences in the Caucasus, including “Nabeg” (1853; “The Raid”) and his three sketches about the Siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War: “Sevastopol v dekabre mesyatse” (“Sevastopol in December”), “Sevastopol v maye” (“Sevastopol in May”), and “Sevastopol v avguste 1855 goda” (“Sevastopol in August”; all published 1855–56).

The first sketch, which deals with the courage of simple soldiers, was praised by the tsar. Written in the second person as if it were a tour guide, this story also demonstrates Tolstoy’s keen interest in formal experimentation and his lifelong concern with the morality of observing other people’s suffering.

The second sketch includes a lengthy passage of a soldier’s stream of consciousness (one of the early uses of this device) in the instant before he is killed by a bomb. In the story’s famous ending, the author, after commenting that none of his characters are truly heroic, asserts that the hero of my story whom I love with all the power of my soul…who was, is, and ever will be beautiful is the truth.

Readers ever since have remarked on Tolstoy’s ability to make such “absolute language,” which usually ruins realistic fiction, aesthetically effective.

From November 1854 to August 1855 Tolstoy served in the battered fortress at Sevastopol in southern Ukraine. He had requested the transfer to this area, a sight of one of the bloodiest battles of the Crimean War (1853–1956); when Russia battled England and France over land). As he directed fire from the Fourth Bastion, the hottest area in the conflict for a long while, Tolstoy managed to write Youth, the second part of his autobiographical trilogy. He also wrote the three Sevastopol Tales at this time, revealing the distinctive Tolstoyan vision of war as a place of unparalleled confusion and heroism, a special space where men, viewed from the author’s neutral, godlike point of view, were at their best and worst.

After completing Childhood, Tolstoy started writing about his day-to-day life at the Army outpost in the Caucasus. However, he did not complete the work, entitled The Cossacks, until 1862, after he had already left the Army.

His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived. The Cossacks (1863) describes the Cossack life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. Anna Karenina (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy not only drew from his own life experiences but also created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in War and Peace, Levin in Anna Karenina and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in Resurrection.

A portion of the novel was first published in the Russian Messenger in 1865, under the title “The Year 1805.” By 1868, he had released three more chapters. A year later, the novel was complete. Both critics and the public were buzzing about the novel’s historical accounts of the Napoleonic Wars, combined with its thoughtful development of realistic yet fictional characters. The novel also uniquely incorporated three long essays satirizing the laws of history. Among the ideas that Tolstoy extols in War and Peace is the belief that the quality and meaning of one’s life is mainly derived from his day-to-day activities.

From 1873 to 1877 Tolstoy worked on the second of his masterworks, Anna Karenina, which also created a sensation upon its publication. The concluding section of the novel was written during another of Russia’s seemingly endless wars with Turkey. The novel was based partly on events that had occurred on a neighboring estate, where a nobleman’s rejected mistress had thrown herself under a train. It again contained great chunks of disguised biography, especially in the scenes describing the courtship and marriage of Kitty and Levin. Tolstoy’s family continued to grow, and his royalties (money earned from sales) were making him an extremely rich man.

The first sentence of Anna Karenina is among the most famous lines of the book: “All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina was published in installments from 1873 to 1877, to critical and public acclaim. The royalties that Tolstoy earned from the novel contributed to his rapidly growing wealth.

War and Peace are generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its dramatic breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical with others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of Napoleon, from the court of Alexander I of Russia to the battlefields of Austerlitz and Borodino. Tolstoy’s original idea for the novel was to investigate the causes of the Decembrist revolt, to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that Andrei Bolkonsky’s son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy’s theory of history and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander.

The essays in War and Peace, which begin in the second half of the book, satirize all attempts to formulate general laws of history and reject the ill-considered assumptions supporting all historical narratives. In Tolstoy’s view, history, like a battle, is essentially the product of contingency, has no direction, and fits no pattern. The causes of historical events are infinitely varied and forever unknowable, and so historical writing, which claims to explain the past, necessarily falsifies it. The shape of historical narratives reflects not the actual course of events but the essentially literary criteria established by earlier historical narratives.

After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes and his later novels such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? develop a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy which led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901. For all the praise showered on Anna Karenina and War and Peace, Tolstoy rejected the two works later in his life as something not as true of reality.

Despite the success of Anna Karenina, following the novel’s completion, Tolstoy suffered a spiritual crisis and grew depressed. Struggling to uncover the meaning of life, Tolstoy first went to the Russian Orthodox Church but did not find the answers he sought there. He came to believe that Christian churches were corrupt and, in lieu of organized religion, developed his own beliefs. He decided to express those beliefs by founding a new publication called The Mediator in 1883.

In 1883 Tolstoy met V. G. Chertkov, a wealthy guard officer who soon became the moving force behind an attempt to start a movement in Tolstoy’s name. In the next few years a new publication was founded (the Mediator ) in order to spread Tolstoy’s word in tract (pamphlets) and fiction, as well as to make good reading available to the poor. In six years almost twenty million copies were distributed. Tolstoy had long been watched by the secret police, and in 1884 copies of What I Believe were seized from the printer.

During this time Tolstoy’s relations with his family were becoming increasingly strained. The more of a saint he became in the eyes of the world, the more of a devil he seemed to his wife. He wanted to give his wealth away, but she would not hear of it. An unhappy compromise was reached in 1884 when Tolstoy assigned to his wife the copyright to all his works before 1881.

In addition to his religious tracts, Tolstoy continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Among his later works’ genres were moral tales and realistic fiction. One of his most successful later works was the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich, written in 1886. In Ivan Ilyich, the main character struggles to come to grips with his impending death. The title character, Ivan Ilyich, comes to the jarring realization that he has wasted his life on trivial matters, but the realization comes too late.

In 1899 Tolstoy published his third long novel, Voskreseniye (Resurrection); he used the royalties to pay for the transportation of a persecuted religious sect, the Dukhobors, to Canada. The novel’s hero, the idle aristocrat Dmitry Nekhlyudov, finds himself on a jury where he recognizes the defendant, the prostitute Katyusha Maslova, as a woman whom he once had seduced, thus precipitating her life of crime. After she is condemned to imprisonment in Siberia, he decides to follow her and, if she will agree, to marry her. In the novel’s most-remarkable exchange, she reproaches him for his hypocrisy: once you got your pleasure from me, and now you want to get your salvation from me, she tells him. She refuses to marry him, but, as the novel ends, Nekhlyudov achieves spiritual awakening when he, at last, understands Tolstoyan truths, especially the futility of judging others. The novel’s most-celebrated sections satirize the church and the justice system, but the work is generally regarded as markedly inferior to War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

In 1908, Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu outlining his belief in non-violence as a means for India to gain independence from British colonial rule. In 1909, a copy of the letter was read by Gandhi, who was working as a lawyer in South Africa at the time and just becoming an activist. Tolstoy’s letter was significant for Gandhi, who wrote Tolstoy seeking proof that he was the real author, leading to further correspondence between them.

Tolstoy also became a major supporter of the Esperanto movement. Tolstoy was impressed by the pacifist beliefs of the Doukhobors and brought their persecution to the attention of the international community after they burned their weapons in a peaceful protest in 1895. He aided the Doukhobors in migrating to Canada. In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Tolstoy condemned the war and wrote to the Japanese Buddhist priest Soyen Shaku in a failed attempt to make a joint pacifist statement.

Over the last 30 years of his life, Tolstoy established himself as a moral and religious leader. His ideas about nonviolent resistance to evil influenced the likes of social leader Mahatma Gandhi.

Also during his later years, Tolstoy reaped the rewards of international acclaim. Yet he still struggled to reconcile his spiritual beliefs with the tensions they created in his home life. His wife not only disagreed with his teachings, she disapproved of his disciples, who regularly visited Tolstoy at the family estate. Their troubled marriage took on an air of notoriety in the press. Anxious to escape his wife’s growing resentment, in October 1910, Tolstoy, his daughter, Aleksandra, and his physician, Dr. Dushan P. Makovitski, embarked on a pilgrimage. Valuing their privacy, they traveled incognito, hoping to dodge the press, to no avail.

Tolstoy’s late works also include a satiric drama, Zhivoy trup (written 1900; The Living Corpse), and a harrowing play about peasant life, Vlast tmy (written 1886; The Power of Darkness). After his death, a number of unpublished works came to light, most notably the novella Khadji-Murat (1904; Hadji-Murad), a brilliant narrative about the Caucasus reminiscent of Tolstoy’s earliest fiction.

Death and Legacy

(Tolstoy’s grave with flowers at Yasnaya Polyana)

Tolstoy died in 1910, at the age of 82. Just prior to his death, his health had been a concern of his family, who were actively engaged in his care on a daily basis. During his last few days, he had spoken and written about dying. He was buried at the family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in Tula Province, where Tolstoy had lost so many loved ones yet had managed to build such fond and lasting memories of his childhood. Tolstoy was survived by his wife and their brood of 8 children. (The couple had spawned 13 children in all, but only 10 had survived past infancy.)

Tolstoy died of pneumonia at Astapovo train station, after a day’s rail journey south. The station master took Tolstoy to his apartment, and his personal doctors were called to the scene. He was given injections of morphine and camphor.

The police tried to limit access to his funeral procession, but thousands of peasants lined the streets. Still, some were heard to say that, other than knowing that “some nobleman had died”, they knew little else about Tolstoy. According to some sources, Tolstoy spent the last hours of his life preaching love, nonviolence, and Georgism to his fellow passengers on the train.

In contrast to other psychological writers, such as Dostoyevsky, who specialized in unconscious processes, Tolstoy described conscious mental life with unparalleled mastery. His name has become synonymous with an appreciation of contingency and of the value of the everyday activity. Oscillating between skepticism and dogmatism, Tolstoy explored the most-diverse approaches to human experience. Above all, his greatest works, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, endure as the summit of realist fiction.

Information Source: