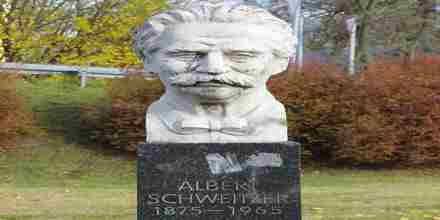

Albert Schweitzer – Theologian, Organist, Philosopher, and Physician (1875-1965)

Name: Albert Schweitzer

Date of birth: 14 January 1875

Place of birth: Kaysersberg, Alsace-Lorraine, Germany (now Haut-Rhin, France)

Date of death: 4 September 1965 (aged 90)

Place of death: Lambaréné, Gabon

Citizenship: German (1875–1919), French (1919–1965)

Fields: Medicine, music, philosophy, theology

Known for: Musicology, philanthropy, theology

Spouse: Helene Bresslau, daughter of Harry Bresslau

Early Life

Albert Schweitzer was born on 14 January 1875, in Kaysersberg, Alsace-Lorraine, Germany (now Haut-Rhin, France). He was a German born French theologian, organist, philosopher, physician, and medical missionary.

(Albert Schweitzer’s birthplace, Kaysersberg.)

(Albert Schweitzer’s birthplace, Kaysersberg.)

He was born in the German province of Alsace-Lorraine and although that region had been reintegrated into the German Empire four years earlier, and remained a German province until 1918, he considered himself French and wrote mostly in French. His mother-tongue was Alsatian German.

Schweitzer, a Lutheran, challenged both the secular view of Jesus as depicted by historical-critical methodology current at this time in certain academic circles, as well as the traditional Christian view. His contributions to the interpretation of Pauline Christianity are noteworthy because they concern the role of Paul’s mysticism of “being in Christ” as primary in importance rather than the secondary doctrine of Justification by Faith.

He received the 1952 Nobel Peace Prize for his philosophy of “Reverence for Life”, expressed in many ways, but most famously in founding and sustaining the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné, now in Gabon, west central Africa (then French Equatorial Africa).

Schweitzer is also greatly known as a music scholar and organist who was a profound scholar of the music of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. Many of his Bach recordings are currently available on CD. He started and greatly influenced the Organ reform movement.

Schweitzer was the founder of universal ethical philosophy and universal reality. He is best known for challenging the secular view of Jesus as depicted by historical-critical methodology present during his time in certain academic circles, as well as the traditional Christian view, depicting a Jesus Christ who saw himself as the world-saving Messiah.

Childhood and Educational Career

Albert Schweitzer was born on 14 January 1875 in Kaysersberg, (Alsace-Lorraine), Germany (presently Haut-Rhin, France). He spent most part of childhood in the village of Gunsbach, Alsace where his father, the local Lutheran-Evangelical pastor taught him to play music. He was brought up in an environment of religious tolerance where he grew up in true Christian beliefs that Christianity always work towards a unity of faith and purpose. In 1893 he received his “Abitur” (the certificate at the end of secondary education) from Mulhouse high school. In the period between 1885-1893 Schweitzer studied organ at Mulhouse high school under Eugène Munch, organist of the Protestant Temple who besides teaching Schweitzer how to play organ also instilled in him profound enthusiasm for the music of German composer Richard Wagner. In 1893 he played under French organist Charles-Marie Widor at Saint-Sulpice, Paris. Widor was extremely impressed with Schweitzer innate talent and agreed to teach Schweitzer for free. This was the beginning of a great friendship and engagement.

(University in Strasbourg)

(University in Strasbourg)

From 1893 Schweitzer studied Protestant theology at the Kaiser Wilhelm University in Strasbourg. There he also received instruction in piano and counterpoint from professor Gustav Jacobsthal, and associated closely with Ernest Munch (the brother of his former teacher), organist of St William church, who was also a passionate admirer of J.S. Bach’s music. Schweitzer served his one-year compulsory military service in 1894. Schweitzer saw many operas of Richard Wagner in Strasbourg (under Otto Lohse) and in 1896 he managed to afford a visit to the Bayreuth to see Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal which deeply impressed him. In 1898 he went back to Paris to write a PhD dissertation on The Religious Philosophy of Kant at the Sorbonne, and to study in earnest with Widor. Here he often met with the elderly Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. He also studied piano at that time with Marie Jaëll. He completed his theology degree in 1899 and published his PhD thesis at the University of Tübingen in 1899.

(University of Tübingen)

(University of Tübingen)

Musical Career

Schweitzer rose to his musical career very swiftly and started being known as a greatly dedicated musical scholar and organist who also devoted his time in rescuing, restoring and studying the history of pipe organs. With his theological background he interpreted the use of pictorial and symbolical representation in J. S. Bach’s religious music. In 1899 Schweitzer greatly surprised Widor by elaborately explaining the figures and motifs in Bach’s Chorale Preludes as painter-like tonal and rhythmic imagery illustrating themes from the words of the hymns on which they were based. He kept studying on the exploration of these illustrations and images on the encouragement of Widor and Munch and it resulted in bringing out his masterly study ‘J. S. Bach: Le Musicien-Poète’ written in French and published in 1905. In 1905 Widor and Schweitzer were among the six musicians to found the Paris Bach Society, a choir dedicated to performing J.S. Bach’s music, for whose concerts Schweitzer took the organ part regularly until 1913.

Schweitzer’s interpretative approach greatly influenced the modern understanding of Bach’s music. He became a welcome guest at the Wagners’ home, Wahnfried. He also corresponded with composer Clara Faisst and the two became good friends.

His pamphlet “The Art of Organ Building and Organ Playing in Germany and France” (1906, republished with an appendix on the state of the organ-building industry in 1927) effectively launched the 20th-century Orgelbewegung, which turned away from romantic extremes and rediscovered baroque principles—although this sweeping reform movement in organ building eventually went further than Schweitzer himself had intended.

Schweitzer also studied piano under Isidor Philipp, head of the piano department at the Paris Conservatory.

Schweitzer, who insisted that the score should show Bach’s notation with no additional markings, wrote the commentaries for the Preludes and Fugues, and Widor those for the Sonatas and Concertos: six volumes were published in 1912–14. Three more, to contain the Chorale Preludes with Schweitzer’s analyses, were to be worked on in Africa: but these were never completed, perhaps because for him they were inseparable from his evolving theological thought.

On departure for Lambaréné in 1913 he was presented with a pedal piano, a piano with pedal attachments; to operate like an organ pedal-keyboard. Built especially for the tropics, it was delivered by river in a huge dug-out canoe to Lambaréné, packed in a zinc-lined case. At first he regarded his new life as a renunciation of his art, and fell out of practice: but after some time he resolved to study and learn by heart the works of Bach, Mendelssohn, Widor, César Franck, and Max Reger systematically. It became his custom to play during the lunch hour and on Sunday afternoons. Schweitzer’s pedal piano was still in use at Lambaréné in 1946. And according to a visitor, Dr. Gaine Cannon, of Balsam Grove, N.C., the old, dilapidated piano-organ was still being played by Dr. Schweitzer in 1962 and stories told that “his fingers were still lively” on the old instrument at 88 years of age.

Theological Life

In 1899 Schweitzer turned a deacon at the church Saint-Nicolas of Strasbourg. In 1900 he completed his licentiate in theology and was appointed as the curate. In 1900 itself, he witnessed the Oberammergau Passion Play. In 1901 he was appointed as provisional Principal of the Theological College of Saint Thomas (from which he had just graduated). In 1903 Schweitzer was made a permanent Principal of the Theological College of Saint Thomas.

From 1890s Schweitzer had believed in the idea that as a Christian his work was to repay the world something for the happiness which it had given to him. In 1906 he published “Geschichte der Leben-Jesu-Forschung” (“History of Life-of-Jesus research”) which made him become very reputed. The book was first translated into English by William Montgomery and published in 1910 as ‘The Quest of the Historical Jesus’. The book became popular in the English speaking world and was brought out in its second German edition in 1913 comprising of theologically significant revisions and expansions (edited and revised edition did not appear in English until 2001).

In The Quest, Schweitzer reviewed all former work on the “historical Jesus” back to the late 18th century. He showed that the image of Jesus had changed with the times and outlooks of the various authors, and gave his own synopsis and interpretation of the previous century’s findings. He maintained that the life of Jesus must be interpreted in the light of Jesus’ own convictions, which reflected late Jewish eschatology.

Schweitzer writes:

The Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the ethic of the kingdom of God, who founded the kingdom of heaven upon earth and died to give his work its final consecration never existed. He is a figure designed by rationalism, endowed with life by liberalism, and clothed by modern theology in a historical garb. This image has not been destroyed from outside; it has fallen to pieces…

Medicine Career

Despite all the resistance and protestations he encountered, in January 1905, at the age of 30, Albert Schweitzer began his studies in medicine, receiving his degree with a specialization in tropical medicine and surgery at the age of 38. What he had not anticipated was that, even though Dr. Schweitzer had rearranged his life to meet the most urgent need expressed by The Paris Missionary Society, they turned him down! On the basis of his theological views, Albert Schweitzer, minister and now physician, was rejected by the Society on the grounds that “it would only intensify their problem by encouraging intellectuals and freethinkers who could only disrupt the mission enterprise and confuse the natives with their theological improvisations… They were not about to sponsor Schweitzer and open the floodgates to other liberals and radicals.” Today, we would characterize the Paris Missionary’s view of Albert Schweitzer as a person who was “politically incorrect!”

Even in his study of medicine, and through his clinical course, Schweitzer pursued the ideal of the philosopher-scientist. By extreme application and hard work, he completed his studies successfully at the end of 1911. His medical degree dissertation was another work on the historical Jesus, The Psychiatric Study of Jesus.

In 1912, now armed with a medical degree, Schweitzer made a definite proposal to go as a medical doctor to work at his own expense in the Paris Missionary Society’s mission at Lambaréné on the Ogooué river, in what is now Gabon, in Africa (then a French colony). He refused to attend a committee to inquire into his doctrine, but met each committee member personally and was at last accepted. Through concerts and other fund-raising, he was ready to equip a small hospital. In spring 1913, he and his wife set off to establish a hospital (Albert Schweitzer Hospital) near an already existing mission post. The site was nearly 200 miles (14 days by raft) upstream from the mouth of the Ogooué at Port Gentil (Cape Lopez) (and so accessible to external communications), but downstream of most tributaries, so that internal communications within Gabon converged towards Lambaréné.

When World War I broke out in summer of 1914, Schweitzer and his wife, German citizens in a French colony, were put under supervision at Lambaréné by the French military, where Schweitzer continued his work. In 1917, exhausted by over four years’ work and by tropical anaemia, they were taken to Bordeaux and interned first in Garaison and then from March 1918 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. In July 1918, after being transferred to his home in Alsace, he was a free man again. At this time Schweitzer, born a German citizen, had his parents’ former (pre-1871) French citizenship reinstated and became a French citizen. Then, working as medical assistant and assistant-pastor in Strasbourg, he advanced his project on The Philosophy of Civilization, which had occupied his mind since 1900. By 1920, his health recovering, he was giving organ recitals and doing other fund-raising work to repay borrowings and raise funds for returning to Gabon. In 1922, he delivered the Dale Memorial Lectures in Oxford University, and from these in the following year appeared Volumes I and II of his great work, The Decay and Restoration of Civilization and Civilization and Ethics. The two remaining volumes, on The World-View of Reverence for Life and a fourth on the Civilized State, were never completed.

One perhaps little-known aspect of Dr. Schweitzer’s personality was his sense of humor. To cite just two examples of many: Once, in the middle of a banquet in his honor, Dr. Schweitzer was being pestered to the point of harassment by a journalist who simply did not understand the philosophy of Reverence for Life and repeatedly demanded that Dr. Schweitzer elaborate it for him. “Finally he said, ‘Reverence for Life means all life. I am a life. I am hungry. You should respect my right to eat.’ With that, he excused himself and returned to the banquet.”

The second example deals with a very common faux pas which it may surprise you to learn that Dr. Schweitzer was well aware of. “He reported… that once he was traveling on a train in America when two girls came up to him and asked: ‘Dr. Einstein, will you give us your autograph?’ ‘I did not want to disappoint them,’ he said, ‘so I signed their autograph book: Albert Einstein, by his friend Albert Schweitzer.'”

Physician, lover of animals, minister, scholarly theologian, environmentalist (Rachel Carson dedicated her seminal work Silent Spring to him), musician and musical scholar, anti-nuclear activist, philosopher, husband, father, friend — these are the many facets of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Today, although in some quarters history is already painting him as a controversial figure, and several different “ism’s” are being attributed to him, one fact remains immutable: In the words of his friend Albert Einstein, Schweitzer “did not preach and did not warn and did not dream that his example would be an ideal and comfort to innumerable people. He simply acted out of inner necessity.”

Personal Career

Albert Schweitzer was born on 14 January 1875 in Kaysersberg, (Alsace-Lorraine), Germany (presently Haut-Rhin, France). He spent most part of childhood in the village of Gunsbach, Alsace where his father, the local Lutheran-Evangelical pastor taught him to play music. He was brought up in an environment of religious tolerance where he grew up in true Christian beliefs that Christianity always work towards a unity of faith and purpose. Schweitzer was a vegetarian.

(Albert Schweitzer and his family)

(Albert Schweitzer and his family)

In June 1912, he married Helene Bresslau, daughter of the Jewish pan-Germanist historian Harry Bresslau.

In spring 1913, he and his wife set off to establish a hospital (Albert Schweitzer Hospital) near an already existing mission post. The site was nearly 200 miles (14 days by raft) upstream from the mouth of the Ogooué at Port Gentil (Cape Lopez) (and so accessible to external communications), but downstream of most tributaries, so that internal communications within Gabon converged towards Lambaréné.

In the first nine months, he and his wife had about 2,000 patients to examine, some travelling many days and hundreds of kilometers to reach him. In addition to injuries, he was often treating severe sandflea and crawcraw sores, framboesia (yaws), tropical eating sores, heart disease, tropical dysentery, tropical malaria, sleeping sickness, leprosy, fevers, strangulated hernias, necrosis, abdominal tumours and chronic constipation and nicotine poisoning, while also attempting to deal with deliberate poisonings, fetishism and fear of cannibalism among the Mbahouin.

Schweitzer’s wife, Helene Schweitzer, was an anaesthetist for surgical operations. After briefly occupying a shed formerly used as a chicken hut, in autumn 1913 they built their first hospital of corrugated iron, with two 13-foot rooms (consulting room and operating theatre) and with a dispensary and sterilising room in spaces below the broad eaves. The waiting room and dormitory (42 by 20 feet) were built, like native huts, of unhewn logs along a 30-yard path leading from the hospital to the landing-place. The Schweitzers had their own bungalow and employed as their assistant Joseph, a French-speaking Galoa (Mpongwe) who first came as a patient.

One year after their arrival at Lambaréné, World War I broke out. Because of their German citizenship, the Schweitzers were enemy aliens in the French colony. From the first prisoner of war camp in the Pyrenees, they were taken to a camp in St. Remy. Here, Schweitzer had odd feelings of déjà vu, feeling as though “he knew the room from some past experience.

In 1918, Albert and Helen returned to Alsace, where their daughter Rhena was born on January 14, 1919.

By 1920 his health had recovered and he started giving organ recitals besides engaging himself in other fund-raising work to repay borrowings and raise funds for returning to Gabon. In 1922 he delivered the Dale Memorial Lectures in Oxford University. In 1923 Volumes I and II of his great work, “The Decay and Restoration of Civilization” and “Civilization and Ethics” were published. These were based on his lectures.

(Albert Schweitzer and his wife)

(Albert Schweitzer and his wife)

In 1924 he returned to Gabon, without his wife but with an Oxford undergraduate, Noel Gillespie, as assistant. His hospital building was totally decayed. He started off with additional medical staff, nurse (Miss) Kottmann and Dr. Victor Nessmann and Dr. Mark Lauterberg. In 1925-1926 Schweitzer managed to come up with new hospital buildings and also a ward for white patients thus a village like site was established. After establishing the hospital newly and building a greatly functional medical team, Schweitzer returned to Europe in 1927.

Death

His wife was not able to stay with him after the birth of their daughter and her declining health made Helene Schweitzer leave Lambaréné. In 1923 the family moved to Königsfeld im Schwarzwald, Baden-Württemberg where Schweitzer started constructing a house for the family. Because of the ongoing war from 1939 to 1948 he stayed in Lambaréné.

Weeks prior to his death, an American film crew was allowed to visit Schweitzer and Drs. Muntz and Friedman, both Holocaust survivors, to record his work and daily life at the hospital. The film The Legacy of Albert Schweitzer, narrated by Henry Fonda, was produced by Warner Brothers and aired once. It resides in their vault today in deteriorating condition. Although several attempts have been made to restore and re-air the film, all access has been denied.

(The Schweitzer house and Museum at Königsfeld in the Black Forest)

(The Schweitzer house and Museum at Königsfeld in the Black Forest)

Honours

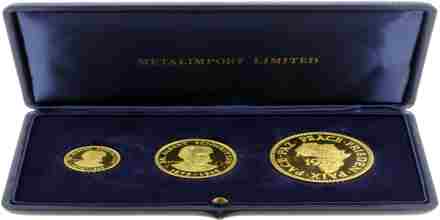

In 1952 he received The “Nobel Peace Prize” for his contribution in the field of philosophy, “Reverence for Life” and his hospital.

In 1955 he was made an honorary member of the Order of Merit by Queen Elizabeth II.