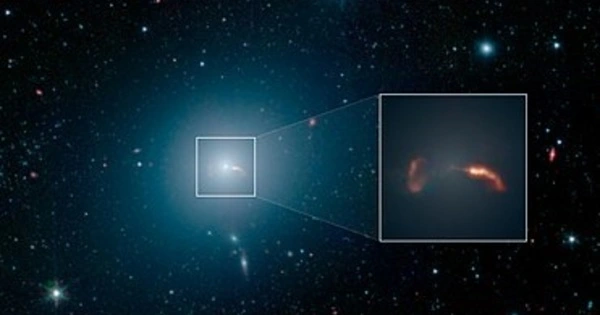

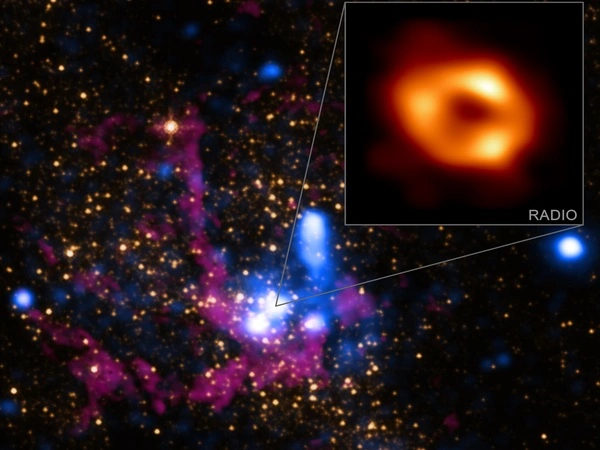

A binary black hole (BBH) is a system made up of two black holes orbiting each other in close proximity. Binary black holes, like black holes, are frequently split into stellar binary black holes, which are created either as remnants of high-mass binary star systems or by dynamic processes including mutual capture, and binary supermassive black holes, which are thought to be the outcome of galactic mergers. A companion black hole appears to orbit a supermassive black hole 9 billion light-years away. The couple gets closer to merging as the orbit reduces.

Scientists are searching astronomy databases for black holes in the hopes of better understanding the unusual objects. However, the desire to discover more black holes is leading some astronomers wrong.

“You say black holes are like needles in haystacks, but suddenly we have a lot more haystacks than we did before,” says astrophysicist Kareem El-Badry of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. “You have a larger chance of discovering them, but you also have a greater chance of finding things that look like them.”

Two more purported black holes have turned out to be the latter: strange phenomena that look like them. El-Badry and his colleagues publish in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society that they are both double-star systems in hitherto unseen stages of evolution. The key to comprehending the systems, according to the researchers, is figuring out how to interpret the light that comes from them.

You say black holes are like needles in haystacks, but suddenly we have a lot more haystacks than we did before. You have a larger chance of discovering them, but you also have a greater chance of finding things that look like them.

Kareem El-Badry

In early 2021, astronomer Tharindu Jayasinghe of Ohio State University and his colleagues announced discovering the Unicorn, a star system around 1,500 light-years from Earth that they believed had a big red star in its senior years orbiting an unseen black hole. Some of the same researchers, including Jayasinghe, later reported the discovery of a second comparable system, known as the Giraffe, some 12,000 light-years away.

Other researchers, like El-Badry, were skeptical that the systems contained black holes. As a result, Jayasinghe, El-Badry, and others banded together to re-analyze the data.

To confirm the nature of each star system, the researchers used stellar spectra, which are rainbows created when sunlight is split up into its component wavelengths. Any star’s spectrum will contain lines indicating where atoms in the stellar atmosphere absorbed specific wavelengths of light. Fast-spinning stars have blurred and smeared lines, but slow-spinning stars have precise lines.

“Basically all the spectral features become nearly invisible if the star rotates fast enough,” El-Badry explains. “Normally, you seek for another set of lines in a spectrum to discover a second star,” he adds. “And that’s more difficult to achieve when a star is quickly revolving.”

That’s why Jayasinghe and colleagues misunderstood each of these systems initially, the team found.

“The trouble was that there was not just one star, but a second one that was virtually concealing,” explains Julia Bodensteiner, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory in Garching, Germany, who was not involved in the current study. The second star in each system spins extremely quickly, making it difficult to see in the spectra.

Furthermore, the lines in the spectrum of a star orbiting something will move back and forth, according to El-Badry. If one assumes that the spectrum reveals only one ordinary, slow-spinning star in orbit, as appears to be the case in these systems at first glance, one is led to the incorrect conclusion that the star is orbiting an invisible black hole.

After reanalyzing the data, the researchers discovered that the Unicorn and Giraffe each hold two stars, captured in a never-before-seen stage of stellar evolution. Both systems contain an older red giant star with a puffy atmosphere and a “subgiant,” a star nearing the end of its existence. The subgiants are close enough to their companion red giants to steal material from them gravitationally. According to El-Badry, when these subgiants gain mass, they spin faster, which is why they were initially invisible.

“Everyone was looking for incredibly intriguing black holes, but what they discovered was really interesting binaries,” explains Bodensteiner.

These are not the only systems that have recently fooled astronomers. What was assumed to be the nearest black hole to Earth turned out to be a pair of stars in a seldom witnessed stage of evolution. “Of course, it’s unfortunate that what we believed were black holes were not, but that’s part of the process,” Jayasinghe adds. He and his colleagues are still seeking for black holes, he says, but with a better understanding of how pairs of interacting stars might fool them.