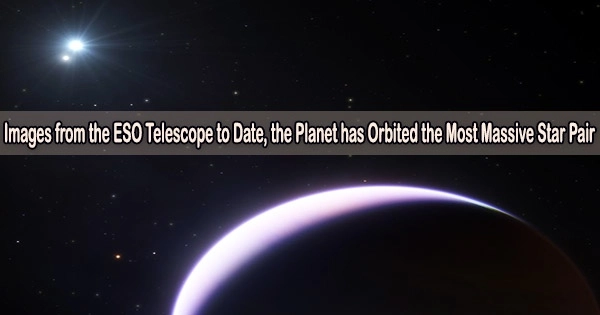

The Very Large Telescope (VLT) of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) has caught a picture of a planet orbiting b Centauri, a two-star system visible with the naked eye. This is the hottest and most massive planet-hosting star system discovered to date, and the planet was discovered orbiting it at a distance 100 times that of Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun.

Until now, some scientists believed planets could not exist around stars this large and intense.

“Finding a planet around b Centauri was very exciting since it completely changes the picture about massive stars as planet hosts,” explains Markus Janson, an astronomer at Stockholm University, Sweden and first author of the new study published online today in Nature.

The b Centauri two-star system (also known as HIP 71865), located around 325 light-years away in the constellation Centaurus, has at least six times the mass of the Sun, making it by far the most massive system around which a planet has been proven.

Until recently, no planets have been discovered orbiting a star more than three times the mass of the Sun.

Most large stars are also extremely hot, and this system is no exception: its main star is a B-type star that is more than three times as hot as the Sun. Because of its high temperature, it emits a lot of ultraviolet and X-ray radiation.

This sort of star’s huge mass and heat have a considerable impact on the surrounding gas, which should work against planet formation. The hotter a star gets, the more high-energy radiation it emits, causing the surrounding material to evaporate quicker.

The planet in b Centauri is an alien world in an environment that is completely different from what we experience here on Earth and in our Solar System. It’s a harsh environment, dominated by extreme radiation, where everything is on a gigantic scale: the stars are bigger, the planet is bigger, the distances are bigger.

Gayathri Viswanath

“B-type stars are generally considered as quite destructive and dangerous environments, so it was believed that it should be exceedingly difficult to form large planets around them,” Janson says.

But the new discovery shows planets can in fact form in such severe star systems. “The planet in b Centauri is an alien world in an environment that is completely different from what we experience here on Earth and in our Solar System,” explains co-author Gayathri Viswanath, a PhD student at Stockholm University. “It’s a harsh environment, dominated by extreme radiation, where everything is on a gigantic scale: the stars are bigger, the planet is bigger, the distances are bigger.”

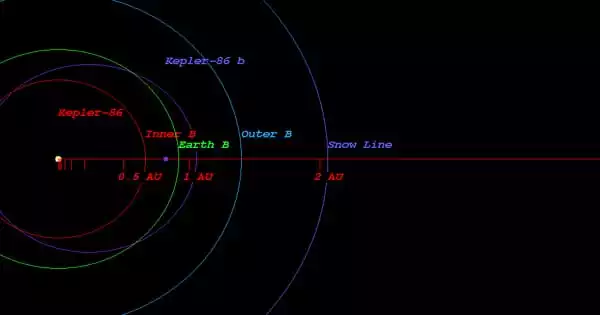

Indeed, the planet discovered, named b Centauri (AB)b or b Centauri b, is also extreme. It is 10 times as massive as Jupiter, making it one of the most massive planets ever found.

Furthermore, it swings around the star system in one of the most expansive orbits yet discovered, at a distance 100 times bigger than Jupiter’s distance from the Sun. This great separation from the center pair of stars may be critical to the planet’s survival.

These results were made possible thanks to the sophisticated Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch instrument (SPHERE) mounted on ESO’s VLT in Chile. SPHERE has successfully imaged several planets orbiting stars other than the Sun before, including taking the first ever-image of two planets orbiting a Sun-like star.

However, SPHERE was not the first instrument to image this planet. The scientists dug into archive data on the b Centauri system as part of their research and discovered that the planet had been observed more than 20 years ago by the ESO 3.6-m telescope, however it was not recognized as a planet at the time.

Astronomers may be able to learn more about this planet’s creation and properties thanks to ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which is set to begin observations later this decade, and enhancements to the VLT.

“It will be an intriguing task to try to figure out how it might have formed, which is a mystery at the moment,” concludes Janson.