Rostows Development model

Creator: Walt Whitman Rostow 1916-2003 was an American economist who proposed his five stage model of development in the 1950’s, the ideas of which stemmed from modern free trade and Adam Smith. Rostow’s model does not deny John Maynard Keynes in that it allows for a degree of government control over domestic development not generally accepted by some ardent free trade advocates. Although empirical at times, Rostow is hardly free of normative discourse. As a basic assumption, Rostow believes that countries want to modernize as he describes modernization, and that society will assent to the materialistic norms of economic growth.

Purpose: requires a country to identify its distinctive or unique economic resources. The model puts forth the idea that a country can develop economically by concentrating on resources in short supply to expand beyond local industries to reach the global market and finance the country’s further development.

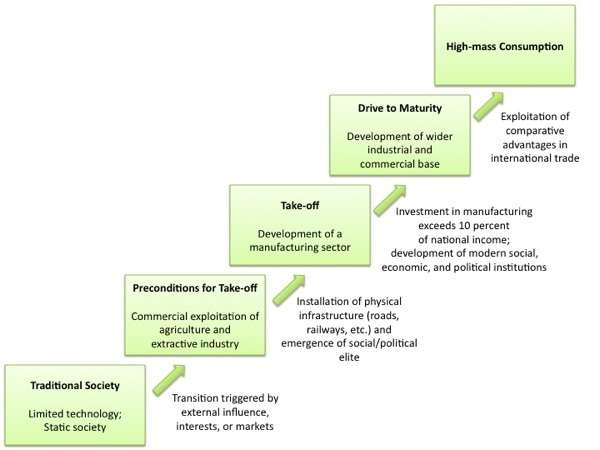

The Five Stages of Development:

1. Traditional Society- Refers to a country that has yet to begin developing, where a high percentage of people are involved with agriculture and a high percentage of the country’s wealth is invested in activities such as the military and religion, seen as “nonproductive” by Rostow. These are societies which have pre-scientific understandings of gadgets, and believe that gods or spirits facilitate the procurement of goods, rather than man and his own ingenuity.

In 1960, the American Economic Historian,WW Rostow suggested that countries passed through five stages of economic development.

2. Transitional Stage- AKA the preconditions for takeoff. Under the model, the process of development begins when an elite group initiates innovations economic activities. Under the influence of these well-educated leaders, the country starts to invest in new technology and infrastructure, such as water supplies and transportation systems. These projects will ultimately stimulate an increase in productivity likely increasing the GDP. There is a limited production function, and therefore a limited output. There are limited economic techniques available and these restrictions create a limit to what can be produced. Increased specialization generates surpluses for trading. There is an emergence of a transport infrastructure to support trade. External trade also occurs concentrating on primary products.

3. Takeoff- Rapid growth is generated in a limited number of economic activities, such as textiles or food products. These few, takeoff industries achieve technical advances and become productive, whereas other sectors of the economy remain dominated by traditional practices. After take-off, a country will take as long as fifty to one hundred years to reach maturity. Globally, this stage occurred during the Industrial Revolution. Industrialization increases, with workers switching from the agricultural sector to the manufacturing sector. The level of investment reaches over 10% of GNP. The growth is self-sustaining as investment leads to increasing incomes in turn generating more savings to finance further investment.

4. Drive to maturity- Modern technology, previously confined to a few takeoff industries, diffuses to a wide variety of industries, which then experience rapid growth comparable to the takeoff industries. Workers become more skilled and specialized. The economy is diversifying into new areas the economy is producing a wide range of goods and services and there is less reliance on imports.

5. High Mass Consumption- AKA age of mass consumption. The economy shifts from production of heavy industry such as steel and energy, to consumer goods, such as motor vehicles and refrigerators. Of particular note is the fact that Rostow’s “Age of High Mass Consumption” dovetails with (occurring before) Daniel Bell’s hypothesized “Post-Industrial Society.” The Bell and Rostovian models collectively suggest that economic maturation inevitably brings on job-growth which can be followed by wage escalation in the secondary economic sector (manufacturing), which is then followed by dramatic growth in the tertiary economic sector (commerce and services).

Main Points & Examples:

Rostow’s development model was based on two factors. First, the developed countries of Western Europe and Anglo-America? had been joined by others in Southern and Eastern Europe and Japan. Second, many LDCs contain an abundant supply of raw materials sought by manufacturers and producers in MDCs. In the past, European colonial powers extracted many of these resources without paying compensation to the colonies, as core countries do to periphery. In a global economy, the sale of these raw materials could generate funds for LDCs to promote development.

– According to the model, each country is in one of these five stages of development. With MDC’s in stage 4 or 5, whereas LDCs are in one of the three earlier stages. The model asserts that today’s MDC’s passed through the other stages in the past. For example, the U.S. was in stage 1 prior to independence, stage 2 during the 1st half of the 1800’s, stage 3 during the middle of the 1880’s, and stage 4 during the late 1800’s, before entering stage 5 during the early 1900’s. The model assumes that LDCs will achieve development by moving along from an earlier to a later stage.

– A country that concentrates on international trade benefits from exposure to consumers in other countries. To remain competitive, the takeoff industries must constantly evaluate changes in international consumer preferences, marketing strategies, production engineering, and design technologies.

– Examples of countries adopting this method of development include areas in East/Southeast Asia and Arabian Peninsula.

In Southeast Asia, a group of countries, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, and the former British colony of Hong Kong came to be known as the “four dragons” after adopting the international trade approach. They were lacking in natural resources so they promoted development by concentrating on producing a handful of manufactured goods, especially clothing and electronics. Low labor costs enabled these countries to sell products inexpensively in MDCs.

The countries of the Arabian Peninsula, which includes Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, went from LDC’s to some of the wealthiest countries almost overnight due to increased petroleum prices during the 1970’s. Arabian Peninsula countries have used petroleum revenues to finance large-scale projects, such as housing, highways, airports, universities, and telecommunications networks.

Weaknesses:

1: Rostow is ‘historical in the sense that the end result is known in the outset and is derived from the historical geography of developed society.

2: Rostow is mechanical in the sense the underlying motor of change is not disclosed and therefore the stages become little more than a classificatory system based on data from developed countries.

3: His model is based on American and European history and aspiring to American norm of high mass consumption.

4: His model represents a “non-communist manifesto” or we can say a “capitalist manifesto”.

Rostow’s thesis is biased towards a western model of modernization, but at the time of Rostow the world’s only mature economies were in the west, and no controlled economies were in the “era of high mass consumption.” The model de-emphasizes differences between sectors in capitalistic vs. communistic societies, but seems to innately recognize that modernization can be achieved in different ways in different types of economies.

The most disabling assumption that Rostow is accused of is trying to fit economic progress into a linear system. This charge is correct in that many countries make false starts, reach a degree of transition and then slip back, or as is the case in contemporary Russia, slip back from high mass consumption (or almost) to a country in transition. On the other hand, Rostow’s analysis seems to emphasize success because it is trying to explain success. To Rostow, if a country can be a disciplined, uncorrupt investor in itself, can establish certain norms into its society and polity, and can identify sectors where it has some sort of advantage, it can enter into transition and eventually reach modernity. Rostow would point to a failure in one of these conditions as a cause for non-linearity.

Another problem is that Rostow’s work considers mostly large countries: countries with a large population (Japan), with natural resources available at just the right time in its history (Coal in Northern European countries), or with a large land mass (Argentina). He has little to say about small countries, such as Rwanda, which do not have such advantages. Neo-liberal economic theory to Rostow, and many others, does offer hope to much of the world that economic maturity is coming and the age of high mass consumption is nigh.

Limitations

Many development economists argue that Rostows’s model was developed with Western cultures in mind and not applicable to LDCs. It addition its generalized nature makes it somewhat limited. It does not set down the detailed nature of the pre-conditions for growth. In reality, policy makers are unable to clearly identify stages as they merge together. Thus as a predictive model it is not very helpful. Perhaps its main use is to highlight the need for investment. Like many of the other models of economic developments it is essentially a growth model and does not address the issue of development in the wider context.

Rostow’s thesis is biased towards a western model of modernization, but at the time of Rostow the world’s only mature economies were in the west, and no controlled economies were in the “era of high mass consumption.” The model de-emphasizes differences between sectors in capitalistic vs. communistic societies, but seems to innately recognize that modernization can be achieved in different ways in different types of economies.

The most disabling assumption that Rostow is accused of is trying to fit economic progress into a linear system. This charge is correct in that many countries make false starts, reach a degree of transition and then slip back, or as is the case in contemporary Russia, slip back from high mass consumption (or almost) to a country in transition. On the other hand, Rostow’s analysis seems to emphasize success because it is trying to explain success. To Rostow, if a country can be a disciplined, uncorrupt investor in itself, can establish certain norms into its society and polity, and can identify sectors where it has some sort of advantage, it can enter into transition and eventually reach modernity. Rostow would point to a failure in one of these conditions as a cause for non-linearity.

Another problem that Rostow’s work has is that it considers mostly large countries: countries with a large population (Japan), with natural resources available at just the right time in its history (Coal in Northern European countries), or with a large land mass (Argentina). He has little to say and indeed offers little hope for small countries, such as Rwanda, which do not have such advantages. Neo-liberal economic theory to Rostow, and many others, does offer hope to much of the world that economic maturity is coming and the age of high mass consumption is nigh. But that does leave a sort of ‘grim meat hook future’ for the outliers, which do not have the resources, political will, or external backing to become competitive.