About Homeostasis

Definition

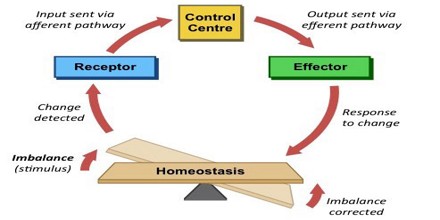

Homeostasis is a healthy state that is maintained by the constant adjustment of biochemical and physiological pathways. It is the maintenance (the body’s physiological mechanisms) of relatively stable conditions within the body’s internal environment. It is a key concept in understanding how our body works. It means keeping things constant and comes from two Greek words: ‘homeo,’ meaning ‘similar,’ and ‘stasis,’ meaning ‘stable.’ The word homeostasis (/ˌhoʊmioʊˈsteɪsᵻs/) uses combining forms of homeo- and -stasis, New Latin from Greek: ὅμοιος homoios, “similar” and στάσις stasis, “standing still”, yielding the idea of “staying the same”.

The concept (Homeostasis) was described by French physiologist Claude Bernard in 1865 and the word was coined by Walter Bradford Cannon in 1926. Homeostasis is happening constantly in our bodies. We eat, sweat, drink, dance, eat some more, have salty fries, and yet our body composition remains almost the same. If someone were to draw our blood on ten different days of a month, the level of glucose, sodium, red blood cells and other blood components would be pretty much constant, regardless of our behavior. It is an almost exclusively biological term, referring to the concepts described by Bernard and Cannon, concerning the constancy of the internal environment (or milieu intérieur) in which the cells of the body live and survive.

There are several examples homeostasis in the human body. Learn how our bodies maintain a state of homeostasis in order to ensure our survival.

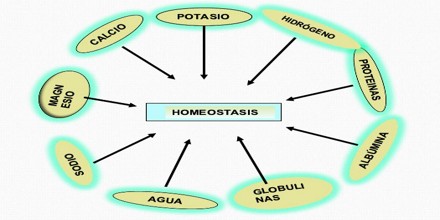

Acid-Base Balance: The body controls the amounts of acids and bases in the blood. When the number of acidic compounds in the blood increases, body acidity also increases. Acid-base balance refers to the balance between alkalinity and acidity in the blood, as measured on the pH scale. The kidneys and lungs, along with buffer systems, help control acid-base balance.

Body Temperature: Another one of the most common examples of homeostasis in humans is the regulation of body temperature. Normal body temperature is 37 degrees C or 98.6 degrees F. Temperatures way above or below these normal levels cause serious complications. The body controls temperature by producing heat or releasing excess heat.

Calcium Levels: The bones and teeth contain approximately 99 percent of the calcium in the body, while the other 1 percent circulates in the blood. Too much calcium in the blood and too little calcium in the blood both have negative effects.

Glucose Concentration: Glucose concentration refers to the amount of glucose – blood sugar – present in the bloodstream. The body uses glucose as a source of energy, but too much or too little glucose in the bloodstream can cause serious complications.

Fluid Volume: The body has to maintain a constant internal environment, which means it must regulate the loss and gain of fluid. Hormones help to regulate this balance by causing the excretion or retention of fluid.

Controlled Systems of Homeostasis

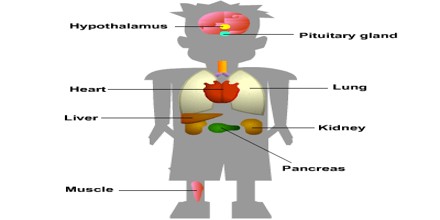

The body’s homeostatic mechanisms are controlled mainly by the Nervous System, and the Endocrine System. The role of parts of these and other tissues varies according to the specific homeostatic mechanism.

Structures within the nervous system detect variation from the balanced state, i.e. parameters such as heat or pH being within the range of acceptable values, and communicate that information by sending signals in the form of nerve impulses to the glands, organs or tissues in the body responsible for taking action to restore the balanced state.

In many cases the glands of the endocrine system (endocrine glands) take action to restore the body or a part or system there of, to a balanced state by producing and/or secreting hormone molecules into the blood. This controls homeostasis because hormones are chemicals that can move around the body and are targeted to interact with specific cells that have receptors matching the specific hormone. Hormones are described as “chemical messengers” because by interacting with target cells they stimulate those cells to take specific action, e.g. antidiuretic hormone (ADH) directs the kidneys to decrease the volume of urine they produce, whose overall effect is to maintain the stability of the body’s internal environment.

The volume of water in the body is measured by stretch receptors in the heart atria, and, somewhat indirectly, by the measurement of the osmolality of the plasma by the hypothalamus. Measurement of the plasma osmolality to give an indication of the water content of the body, relies on the fact that water losses from the body, through sweat, gut fluids, normal fecal water losses, and through vomiting and diarrhea, and the exhaled air, are all hypotonic, meaning that they are less salty than the body fluids compare, for instance, the taste of saliva with that of tears.

Chronic Disease about Homeostasis

Various chronic diseases are kept under control by homeostatic compensation, which masks a problem by compensating for it in another way. However, the compensating mechanisms eventually wear out or are disrupted by a new complicating factor such as the advent of a concurrent acute viral infection, which sends the body reeling through a new cascade of events. Common examples include decompensated heart failure, kidney failure, and liver failure.