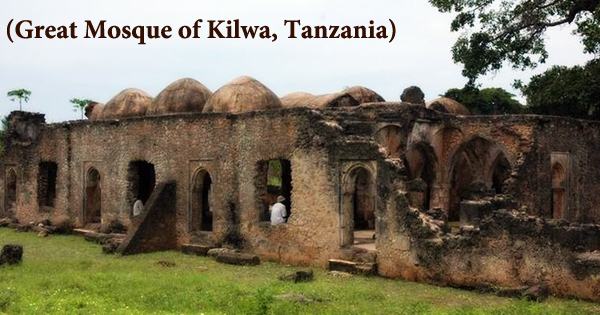

The Great Mosque of Kilwa is a congregational mosque located on the Tanzanian island of Kilwa Kisiwani. Though it is predated by components from the Kizimkazi Mosque in Zanzibar, it is the earliest remaining mosque edifice on the East African coast. The Great Mosque, which presently lies on the outskirts of modern-day Kilwa, was constructed in at least two stages, as seen by the stark contrast between the small northern prayer hall built in the 11th and 12th centuries and the following fourteenth-century southern extension. The smaller northern prayer hall, which was built in the 11th or 12th century, is from the earliest phase of building. It had a total of 16 bays, each supported by nine pillars made of coral that were later replaced with timber. The building, which was totally roofed, was possibly one of the first mosques to be constructed without a courtyard. In the 13th century, side pilasters, timber, and transverse beams were added to the mosque. Built-in the eleventh or twelfth century, the original prayer hall was later remodeled in the thirteenth century. It was divided into 16 bays by nine pillars that supported a flat coral plaster roof. The original pillars were octagonal columns, each measuring 140 centimeters tall and 40 centimeters square, and cut from a single coral stone. Coral stone contains lime, which hardens when exposed to water and saturates the porous coral to form concrete. The qibla axis of this sanctuary was roughly 12 meters long and 7.8 meters wide. The east and west side walls each have three arched entrances with recessed spandrels added in the thirteenth century. Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman, who also built the neighboring Palace of Husuni Kubwa, added a southern expansion in the early fourteenth century, which contained a large dome. Ibn Battuta described this dome after visiting Kilwa in 1331. Ibn Battuta’s descriptions were not totally correct, suggesting that the mosque was entirely composed of wood, despite the fact that stone walls dating back to the fourteenth century had been discovered. The columns were replaced with timber ones during the thirteenth-century modifications, and a more complicated roof support structure, comprising transverse beams and side pilasters, was built. According to the Kilwa Chronicle, stone carving craftsmanship in Kilwa had decreased, thus the beams and columns were made of wood. The ceiling’s coral stones were also plastered with concrete, which was carved with an interlocking circular pattern. The second wall of square-cut coral blocks laid in a thick mortar lined the mosque’s original walls.

The mosque is built on the top of a tiny hill that connects to the qibla, making it wider than it is long. The ceiling structure is supported by oblique arches in the inside. Later, to reinforce them, the second set of arcades was created. An arch tops the external edicule of a mihrab constructed into the walls. The qibla divider’s exterior veneer is reinforced by a 30 cm broad brace that completes the installation. A shattered arch rests on top of two columns with rectangular capitals in this mihrab. A fluted semi-dome and several string courses adorn the recessed apse. Four dressed blocks of coral stone extending from the wall in a shelf to the east of this mihrab, signifying a minbar. Built between 1131 and 1170, the northern section of the Great Mosque is the oldest element of the mosque. All that is left of the northern section are walls with foundations composed of a truly conventional mechanical assembly, coral limestone quadrangular rubble. The nine monochrome polygonal parts that support the leveled roof can still be seen today. An ablution court connected to the mosque by an anteroom to the west of this prayer hall. There was a tank, a well, and a washroom in this underground courtyard, as well as huge round sandstone blocks laid in the floor to exfoliate the feet after washing. A stairway goes to the roof from the court’s south side. The Great Mosque was extended southward between 1294 and 1302 to provide support for a semicircular vault where the Sultan went to pray. This mosque’s southern addition was customarily constructed with square bays separated by a gap in the middle, leaving no central court. Rectangular columns from this period may still be seen on the mosque’s southern wall. Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman, the architect of Husuni Kubwa’s palace, added an expansion from the east wall of the northern prayer hall that wrapped around to form a huge open court in the early fourteenth century. A 30-bay barrel-vaulted hallway with dressed coral panels and supported by coral columns stretched directly south. An earthquake struck in 1331, causing the mosque to collapse and be destroyed. The southern hall was roofed with barrel vaults with domes atop alternate bays sometime between 1421 and 1442. The Great Mosque at Kilwa became the largest covered mosque on Africa’s east coast as a result of its expansion. The southern wall of the addition was knocked through to make a new mihrab in the late eighteenth century, resulting in the roof falling through and being left as a ruin. Internally fluted are the two domes that serve as entrance bays on the eastern side. The southernmost of these fluted domes is accessed through the big dome. The remaining eight bays, which flank the central axis, are barrel-vaulted. A handful of the bays have been trimmed by 20 centimeters due to the slightly uneven angles of the southern court. At the far southwest corner of the southern hall, a massive room with a corbelled roof was constructed. From the south wall, two doorways open to a short lane that connects the Great Mosque with the Great House complex. The ultimate addition of a second mihrab was made somewhat later. The larger congregation’s mihrab is positioned at the northernmost end of the central axis, jutting into the northern prayer hall. The northern half of the mosque, however, was decommissioned and never restored in the eighteenth century, and their status was lowered to village status in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as the mosque is now considered a historic landmark.