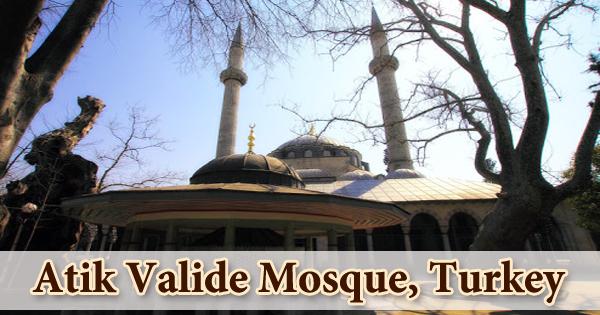

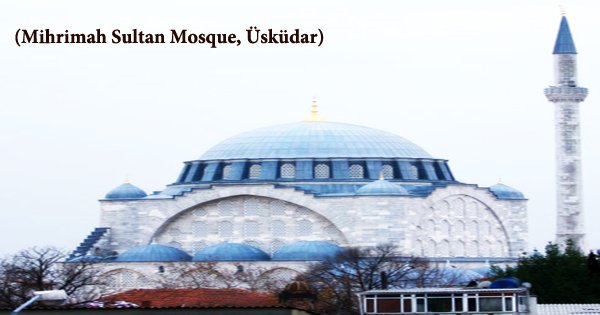

The Atik Valide Mosque (Turkish: Atik Valide Camii, Eski Valide Camii) is one of Mimar Sinan’s two major mosque complexes in Istanbul. Though not as impressive as the Süleymaniye, it was constructed on a similar plan and in a similar commanding position. Due to the presence of female grace in every nook and cranny of Istanbul, it is known as the city of Sultanas. The dignified ladies of the Ottoman harem built several monumental buildings in Üsküdar, including Mihrimah Sultan Mosque (İskele Camii), Emetullah Rabia Gülnuş Sultan Mosque (Yeni Valide Camii), Nurbanu Sultan Mosque (Atik Valide Camii), Mahpeyker Sultan Mosque (Çinili Camii), and Gülfem Hatun Masjid. Selim II (1524-1574) commissioned the Atik Valide complex in 1570 for his wife Nurbanu Sultan, and his son Murad III (1546-1595) completed it in 1579. The mosque is a 16th-century Ottoman imperial mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, situated on a hill above the densely populated district of Üsküdar. The construction of a small mosque with a single minaret started in 1571. The mosque was later enlarged, but it wasn’t finished until 1586, three years after Nurbanu’s death. In 1583, the complex was enlarged. It consists of three building groups divided by streets and two small, free-standing buildings, all of which are built on a site that descends to the northwest. Its extensive külliye (mosque complex) includes a now-decommissioned hamam on Dr Fahri Atabey Caddesi, as well as an imaret (soup kitchen), medrese (Islamic higher education institution), darüşşifa (hospital), and han (caravanserai). At the time of study, they were all being restored. The Atik Valide Mosque (name translation: Old Queen Mother Mosque) was built for Nurbanu Sultan, Selim II’s Venetian-born wife and Murad III’s mother. During the Sultanate of Women, she was the first valide sultan (queen mother) to exercise effective control over the Ottoman Empire from the harem. She was politically astute and founded the “Kadınlar Saltanatı” (Sultanate of Women). This was the start of a period in which some influential women had a huge impact on their husbands’ and sons’ decisions as sultans. Sultan Murat III, her son, commissioned the great master builder Mimar Sinan to erect this memorial on the highest hill in Üsküdar as a token of his love after she died. When she was 12 years old, Turks kidnapped Nurbanu on the Aegean island of Paros, and she ended up as a slave in Topkap. The poor woman had to go through a lot after being kidnapped and then falling in love with Selim the Sot. She was, however, his favorite concubine and a deft competitor in Ottoman politics. She established the Kandınlar Sultanatı (Women’s Rule), in which a succession of powerful women dominated the decisions taken by their sultan husbands and sons. Murat adored his mother and commissioned Sinan to create this memorial in her honor after she died.

Mimar Sinan, the imperial architect, constructed the mosque, which was completed in three phases. Since Sinan was located in Edirne during the construction of the Selimiye Mosque, another imperial architect oversaw the work from the start in 1571 until the completion of the first edition of the mosque in 1574. The dervish hostel (tekke or dergah) on the northeast is the first and smallest of the three-building groups, running from northeast to southwest. The largest building complex, located in the southwest, includes a house for Koran readers (darül-kurra), an Islamic law college (darül-hadis), a hospital with an insane asylum (darüssifa), and a student soup kitchen (imaret). A kitchen, a hospice (tabhane), and a caravanserai are located within the imaret. The mosque, with a wide fountain courtyard surrounding it on three sides and the madrasa attached to the northwest side of the mosque courtyard, stands between the tekke and the imaret cluster. The bathhouse, which is situated on the west side of the complex, is the larger of the two freestanding buildings. The Quranic school (sibyan mektebi), which is smaller, is situated southeast of the mosque. The main space is encircled by a central dome with a diameter of 12.7 meters (42 feet) and is protected by six hexagonal arches and two free-standing columns. Five exedral semi-domes enlarge the vacuum, one of which houses the mihrab. On the north side of the arch, there is a flat wall that houses the entrance portal. Galleries surround the interior on three sides. The courtyard’s centerpiece was an octagonal fountain, of which only the base remains today. Each of the thirty-five cells is accessed through a separate door underneath the portico’s wooden pitched roof. Each cell has a rectangular window with a circular window above it on the courtyard side; the exterior walls are unfenestrated. The cells’ domes are supported by pendentives. Iznik tiles are used to decorate the qibla wall and the mihrab recess. Spring blossoms and flowers are depicted in a pair of paired arched tiled panels on the sidewalls on either side of the mihrab. On the northwestern and southeastern walls of the tevhidhane, there are fourteen windows and two niches with muqarnas carvings. There are ten rectangular calligraphic lunette panels above the windows under the portico on the north facade. When the mosque was expanded, four panels were added, two at each end. The courtyard of the imaret is shaped like a T and is surrounded by thirteen cells. The domes with pendentives that cover the cells have various configurations that correspond to various functions. Each cell is accessed via doors set beneath a U-shaped portico with fourteen columns supporting it. When the hospice buildings were turned into a military hospitals and prisons in the 19th century, upper floors were added. The mihrab niche is situated between two windows within the mihrab projection. The prayer hall is surrounded on three sides by small galleries that are borne over pointed arches by thirty columns. After the mosque was finished, it was altered again around ca. 1835, during Mahmud II’s reign. The fenestration in the prayer hall’s west wall was reconfigured, and a sultan’s platform and a muezzin’s platform were added. The General Directorate of Religious Endowments restored the mosque most recently between 1956 and 1972.