Herminia Pasantes Ordóez was about 14 years old when she overheard her mother telling her father that she would never find a husband. Pasantes had to wear thick glasses because of her poor vision. Her mother saw those glasses as a sign that her future as a “good woman” was doomed. “It made my life easier because it was already stated that I was going to study,” Pasantes says.

Pasantes studied biology at Mexico City’s National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, at a time when it was uncommon for women to become scientists. She was the first person in her family to attend college.

She became a neurobiologist and one of the most important Mexican scientists of her time. Her studies on the role of the chemical taurine in the brain offer deep insights into how cells maintain their size — essential to proper functioning. In 2001, she became the first woman to earn Mexico’s National Prize for Sciences and Arts in the area of physical, mathematical, and natural sciences.

“We basically learned about cell volume regulation through the eyes and work of Herminia,” says Alexander Mongin, a Belarusian neuroscientist at Albany Medical College in New York.

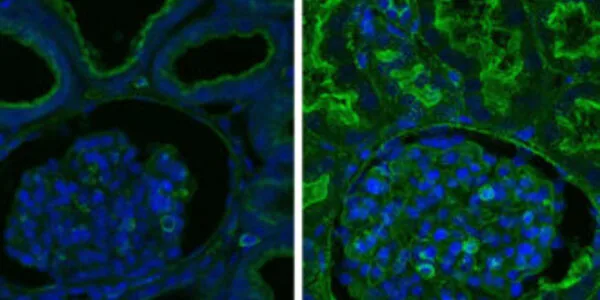

The lab was trying to find out everything there was to know about the retina, the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that is sensitive to light. Pasantes decided to test whether free amino acids, a group that aren’t incorporated into proteins, were present in the retinas and brain of mice.

Pasantes did get married, in 1965 while doing her master’s in biochemistry at UNAM. She had a daughter in 1966 and a son in 1967 before starting a Ph.D. in natural sciences in 1970 at the Center for Neurochemistry at the University of Strasbourg in France. There, she worked in the laboratory of Paul Mandel, a Polish pioneer in neurochemistry.

The lab was trying to find out everything there was to know about the retina, the layer of tissue at the back of the eye that is sensitive to light. Pasantes decided to test whether free amino acids, a group that aren’t incorporated into proteins, were present in the retinas and brain of mice. Her first chromatography — a lab technique that lets scientists separate and identifies the components of a sample — showed an immense amount of taurine in both tissues. Taurine would drive the rest of her scientific career, including work in her own lab, which she started around 1975 at the Institute of Cellular Physiology at UNAM.

Taurine turns out to be widely distributed in animal tissues and has diverse biological functions, some of which were discovered by Pasantes. Her research found that taurine helps maintain cell volume in nerve cells, and that it protects brain, muscle, heart, and retinal cells by preventing the death of stem cells, which give rise to all specialized cells in the body.

Contrary to what most scientists had believed at the time, taurine didn’t work as a neurotransmitter sending messages between nerve cells. Pasantes demonstrated for the first time that it worked as an osmolyte in the brain. Osmolytes help maintain the size and integrity of cells by opening up channels in their membranes to get water in or out.

Pasantes says she spent many years looking for an answer for why there is so much taurine in the brain. “When you ask nature a question, 80 to 90 percent of the time, it responds no,” she says. “But when it answers yes, it’s wonderful.”

Pasantes’ lab was one of the big four labs that did groundbreaking work on cell volume regulation in the brain, says Mongin.

Her work and that of others proved taurine has a protective effect; it’s the reason the chemical is today sprinkled in the containers that carry organs for transplants. Pasantes’ work was the foundation for our understanding of how to prevent and treat brain edema, a condition where the brain swells due to excessive accumulation of fluid, from head trauma or reduced blood supply, for example. She and other experts also reviewed the role of taurine for Red Bull, which added the chemical to its formula because of potentially protective effects in the heart.

Pasantes stopped doing research in 2019 and spends her time talking and writing about science. She hopes her story speaks to women around the world who wish to be scientists: “It is important to send the message that it is possible,” she says.

Her application to the UNAM for a Ph.D. in biochemistry was rejected years before she was accepted into Mandel’s lab. Pasantes claims the reason was that she had recently given birth to her daughter. Looking back, Pasantes describes this experience as “one of the most wonderful things that could’ve happened to me,” because it led her to Strasbourg, where her potential as a researcher blossomed.

Rosa Mara González Victoria, a social scientist specializing in gender studies at the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo in Pachuca, Mexico, recently interviewed Pasantes for a book about Mexican women in science. González Victoria believes Pasantes’ reaction to that early rejection reveals her personality: “A woman that takes those no’s and turns them into yes’s.”