The capacity of decision-making teams to integrate and make sense of information is a major factor in how effective they are. Therefore, teams that use majority decision-making more frequently may produce decisions of higher quality. This is especially true if the teams also have task representations that encourage the elaboration of information pertinent to the decision in the lack of clear leadership.

When a decision needs to be made, groups of individuals frequently conduct a straw poll to gauge opinions prior to the formal vote. A new study from the University of Washington demonstrates that one particular voting method was superior to others in terms of determining the best option.

Researchers found that groups who utilized “multivoting” in unofficial ballots were 50% more likely to choose the right answer than those who used plurality or ranked-choice voting, according to a study published in Academy of Management Discoveries.

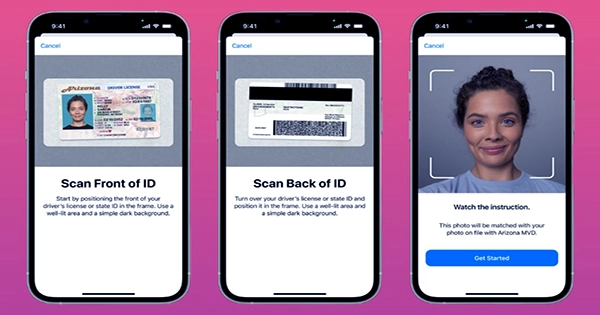

People that use multivoting have many votes to distribute among all possibilities. “American Idol” uses multivoting and gives each fan ten votes. They can cast all ten votes for their preferred competitor or divide them between two or more. Students were given 10 votes to divide among the three options in this study.

“We were surprised that the ranked-choice groups did not outperform the plurality groups. There is a lot of evidence, particularly in politics these days, that ranked-choice voting leads to outcomes that are more consistent with the preferences of the electorate than plurality voting does. That’s why we’ve seen so many political elections move toward ranked-choice voting.

Michael Johnson

Political elections are the most frequently held by plurality voting, in which each voter must choose one choice. In some municipal and state political elections, ranked-choice voting—which is gaining popularity—allows voters to rank their selections in order of preference importance. It is also used to choose the winners of the Academy Awards.

Michael Johnson, co-author, and professor of management in the UW Foster School of Business, said multivoting most benefits groups that want to be sure they’re making the best decision. The researchers don’t believe it would work for political elections, mostly because of how taxing it would be to allocate votes across a variety of options.

“We see multivoting as primarily useful for decision-making groups in workplaces,” Johnson said. “Wherever groups feel like it’s going to be critical to get a decision right, use multivoting as an unofficial vote, look at the distribution, and discuss after that. It works where people are motivated to vote consistent with what they really think rather than trying to strategically vote to counter another person.”

The “pursuit teams” created by the Department of Homeland Security in the wake of 9/11 served as the basis for the UW study. The goal was to link the intelligence agency’s findings to identify potential terrorist threats.

In this study, 93 groups of undergraduate students were instructed to act as counterterrorism support teams in order to determine which of three individuals posed the biggest threat. Three terrorists were revealed to the student groups, although no group member was fully informed about any one suspect. In order to correctly identify the greatest threat, students had to pool their intelligence.

The teams were divided into thirds, and ranked-choice voting, plurality, and multivoting were used to create an even number of groups. To ascertain the initial opinions of the participants in each group regarding the terrorist suspects, a preliminary, unofficial poll was taken. After the informal vote, they evaluated the outcomes and spoke about the potential suspects. Students could select one terrorist who obviously posed a greater threat if they were able to effectively synthesize the information. After that, the teams presented their final judgment.

Only 31% of the teams made the most dangerous suspect their final pick, which is roughly the same as if the decision had been left to chance. In the unofficial poll, 6% of teams correctly identified the culprit with the majority of their members. That is a lower percentage than the 11% that would have occurred by chance.

Ranked-choice voting didn’t fare much better. In the final vote, 32% of teams identified the correct suspect. In the unofficial vote, 7% of groups had a majority of members rank the right suspect as the most threatening.

“We were surprised that the ranked-choice groups did not outperform the plurality groups,” Johnson said. “There is a lot of evidence, particularly in politics these days, that ranked-choice voting leads to outcomes that are more consistent with the preferences of the electorate than plurality voting does. That’s why we’ve seen so many political elections move toward ranked-choice voting.

“But ranked-choice voting is generally better at revealing the true preferences of people and not necessarily getting to the exact right answer. When people are making decisions at work, you’re more concerned about getting it right than about making sure it reveals what everybody thinks.”

The multivoting groups started out stronger, with the majority of members in 30% of the groups selecting the most dangerous suspect. In the end, 45% of teams identified the most dangerous suspect. There was no evidence that discussions in the multivoting groups differed in any meaningful way from the other two voting conditions, according to the researchers. Instead, the benefit of multivoting occurred prior to any discussion as students processed the information more deeply and critically.

“The real discovery, and something we didn’t expect,” Johnson said, “was that multivoting groups were more accurate before they discussed.” “We just assumed they’d be roughly equal before the discussion and then improve at the end. If people have the option to say, ‘I kind of like Option A, but I also kind of like Option B,’ it may cause them to think more before discussing, allowing them to make the best decision.”