Fossil fuels have grown in importance in energy generation since the early industrial revolution in the mid-1700s.

However, environmental concerns about the use of fossil fuels, as well as their eventual depletion, have prompted a global shift toward renewable energy sources. However, these transitions pose concerns regarding the optimal renewables to use and the impact of investing in these resources on consumer costs.

Researchers at Texas A&M University devised a metric that reflects the average price of energy in the United States, according to a recent study published in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers’ statistic represents changes in energy prices caused by the types of energy sources available and their supply chains, similar to how the Dow index reflects fluctuations in stock market pricing.

“Energy is affected by all kinds of events, including political developments, technological breakthroughs, and other happenings going on at a global scale,” said Stefanos Baratsas, a graduate student in the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas A&M and the lead author on the study.

“It’s crucial to understand the price of energy across the energy landscape along with its supply and demand. We came up with one number that reflects exactly that. In other words, our metric monitors the price of energy as a whole on a monthly basis.”

Today, fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and petroleum dominate the energy business. Increased consumption of fossil fuels, particularly in recent decades, has generated worries about their environmental impact.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, has calculated a 0.2-degree Celsius increase in global temperature per decade, which is directly linked to the use of fossil fuels.

However, renewable energy accounts for just about 11% of global energy use. Although several countries, including the United States, have pledged to use more renewable energy sources, there is no mechanism to quantify the price of energy as a whole quantitatively and correctly.

For example, a business might employ a mix of solar and fossil fuels for various reasons such as heating, power, and transportation. In this scenario, it’s unknown how the price would alter if fossil fuel taxes were raised or renewable energy subsidies were implemented.

“Energy transition is a complex process and there is no magic button that one can press and suddenly transition from almost 80% carbon-based energy to 0%,” said Dr. Stratos Pistikopoulos, director of the Texas A&M Energy Institute and senior author on the study. “We need to navigate this energy landscape from where we are now, toward the future in steps. For that, we need to know the consolidated price of energy of end-users. But we don’t have an answer to this fundamental question.”

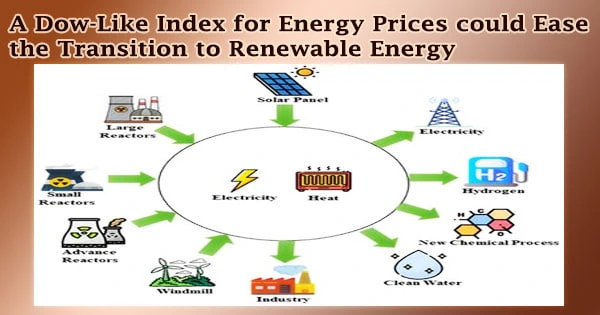

To fill this knowledge vacuum, the researchers first identified various energy feedstocks and associated energy products, such as crude oil, wind, solar, and biomass. Petrol, gasoline, and diesel, for example, are crude oil’s energy products.

Energy is affected by all kinds of events, including political developments, technological breakthroughs, and other happenings going on at a global scale. It’s crucial to understand the price of energy across the energy landscape along with its supply and demand. We came up with one number that reflects exactly that. In other words, our metric monitors the price of energy as a whole on a monthly basis.

Stefanos Baratsas

The energy end consumers were then classified as either residential, commercial, industrial, or transportation. They also received data from the US Energy Information Administration on which energy product each consumer consumes and how much of it they consume.

Finally, they pinpointed the supply chains that linked energy items to end-users. All of this data was used to compute the average energy price for a given month, known as the energy price index, as well as estimate energy costs and demand for future months.

The researchers looked at two policy case studies to see if this statistic might be used in the real world. They looked at how the energy price index would change if a crude oil tax was applied in the first scenario.

One of their primary results after watching the energy price index was that a $5-per-barrel increase in crude oil tax might earn $148 billion in four years.

Furthermore, this tax would not have a major impact on the cost of energy for American consumers on a monthly basis. They discovered that subsidies in the generation of electricity from renewable energy sources can produce a drop in energy prices even if there is no tax credit in the second case study.

According to Baratsas, this model allows policymakers at the state, regional, and national levels to optimize policies for a smooth and efficient transition to sustainable energy.

He also mentioned that their metric could adapt or self-correct its forecasts of energy demands and pricing in the event of unexpected events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which could result in a sharp drop in demand for energy goods.

“This metric can help guide lawmakers, government or non-government organizations and policymakers on whether, say, a particular tax policy or the impact of a technological advance is good or bad, and by how much,” said Pistikopoulos. “We now have a quantitative and accurate, predictive metric to navigate the evolving energy landscape, and that’s the real value of the index.”