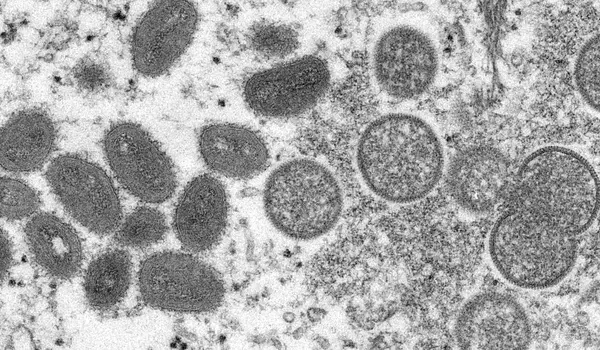

Monkeypox is a rare disease that mostly affects Central and Western Africa. The condition was first identified in 1958, when two outbreaks of a pox-like disease occurred in monkeys kept for research in a Danish facility. The first human case was discovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970. Human cases of monkeypox have been reported in other African countries. A monkeypox outbreak in the United States was discovered in 2003 among people exposed to native prairie dogs who had contact with previously infected imported African rodents.

The World Health Organization’s director-general declared monkeypox a global public health emergency on Saturday. The viral disease has been designated a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, joining the ranks of polio and COVID-19.

Clusters of monkeypox cases were discovered in the United Kingdom and Europe in May. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been 16,836 cases of monkeypox in 74 countries since then. Historically, monkeypox outbreaks were much smaller and occurred in central and western Africa.

“The cases we are seeing are just the tip of the iceberg,” Albert Ko told the Associated Press. Ko is a professor of public health and epidemiology at Yale University. “The window has probably closed for us to quickly stop the outbreaks in Europe and the U.S., but it’s not too late to stop monkeypox from causing huge damage to poorer countries without the resources to handle it.”

The cases we are seeing are just the tip of the iceberg. The window has probably closed for us to quickly stop the outbreaks in Europe and the U.S., but it’s not too late to stop monkeypox from causing huge damage to poorer countries without the resources to handle it.

Albert Ko

Humans are infected with two types of monkeypox. One is more dangerous, with a 10% fatality rate; it has so far only been discovered in Africa. The strain that appears to be driving the global outbreak is a milder strain that is rarely fatal. Both versions cause a fever and a painful rash. Monkeypox viruses can be transmitted through close contact with an infected person or through infected bodily fluids, though scientists are still trying to figure out what’s causing this surge of cases. According to the WHO, the vast majority of cases in the current outbreak have been in men, particularly men who have sex with men. It notes that there has also been an uptick in cases in parts of Africa, where monkeypox patients include more women and children.

The WHO declaration could theoretically assist countries in strengthening their public health response. It included recommendations for how different countries should respond to the virus, regardless of whether they had detected cases or not. Monkeypox, unlike COVID-19, is a well-known pathogen. There are tests and vaccines available for this virus, and while there are no specialized treatments, some antivirals may be effective.

However, the declaration has been a source of contention for several weeks, owing to the virus’s apparent impact on populations all over the world. The virus is mild in Europe and the United States, and countries are stockpiling vaccines for distribution. In Africa, where cases have been fewer, but more serious, no vaccines have been sent out, the Associated Press reports.

Back in June, a panel of experts made the controversial decision that monkeypox did not qualify as a global public health emergency. The WHO defines this kind of emergency as “an extraordinary event, which constitutes a public health risk to other States through international spread, and which potentially requires a coordinated international response.” Today, the panel met again and was split as to whether or not monkeypox actually met those criteria.

The WHO panel members who supported today’s declaration thought it met those standards. They also stated that they had a “moral responsibility to deploy all means and tools available to respond to the event,” citing LGBTI+ leaders from around the world who are particularly concerned that this disease is disproportionately affecting their communities. They noted that “the community currently most affected outside of Africa is the same community that was initially reported to be affected in the early stages of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.” The disease was ignored and stigmatized in the early days of the pandemic because it was associated with gay men.

Panel members who were opposed said the outbreak’s conditions had remained unchanged since their last meeting in June, when they decided not to declare an emergency. They emphasized that the disease has been mild in most of the world and that it may be beginning to stabilize in some countries.

They also expressed concern about the stigma that an emergency health declaration might bring, “particularly in countries where homosexuality is criminalized.” Another source of concern was the world’s still extremely limited supply of monkeypox vaccines. Opponents of the declaration expressed concern that declaring an emergency would increase demand for the vaccine even among people who are not at risk, putting a strain on the vaccine supply.

Even though the panel was divided, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director general of the WHO, decided it was worthwhile to declare an emergency. “We have an outbreak that has spread rapidly around the world through new modes of transmission, about which we know far too little, and that meets the criteria,” Tedros told The New York Times.