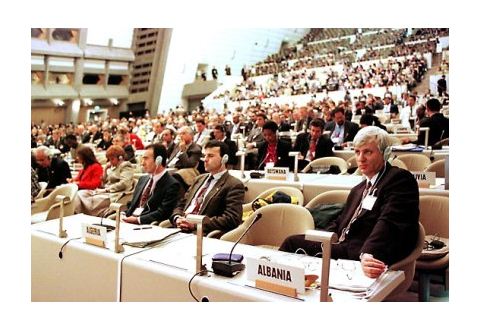

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC or FCCC) is an international environmental treaty produced at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro from June 3 to 14, 1992. The objective of the treaty is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.

The treaty itself set no mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions for individual countries and contains no enforcement mechanisms. In that sense, the treaty is considered legally non-binding. Instead, the treaty provides for updates (called “protocols”) that would set mandatory emission limits. The principal update is the Kyoto Protocol, which has become much better known than the UNFCCC itself.

The UNFCCC was opened for signature on May 9, 1992, after an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee produced the text of the Framework Convention as a report following its meeting in New York from April 30 to May 9, 1992. It entered into force on March 21, 1994. As of May 2011, UNFCCC has 194 parties.

One of its first tasks was to establish national greenhouse gas inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals, which were used to create the 1990 benchmark levels for accession of Annex I countries to the Kyoto Protocol and for the commitment of those countries to GHG reductions. Updated inventories must be regularly submitted by Annex I countries.

The UNFCCC is also the name of the United Nations Secretariat charged with supporting the operation of the Convention, with offices in Haus Carstanjen, Bonn, Germany. From 2006 to 2010 the head of the secretariat was Yvo de Boer; on May 17, 2010 his successor, Christiana Figueres from Costa Rica has been named. The Secretariat, augmented through the parallel efforts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), aims to gain consensus through meetings and the discussion of various strategies.

The parties to the convention have met annually from 1995 in Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was concluded and established legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Annex I, Annex II countries and developing countries Parties to UNFCCC are classified as:

- Annex I countries – industrialized countries and economies in transition

- Annex II countries – developed countries which pay for costs of developing countries

- Non Annex I countries – Developing countries.

Annex I countries which have ratified the Protocol have committed to reduce their emission levels of greenhouse gasses to targets that are mainly set below their 1990 levels. They may do this by allocating reduced annual allowances to the major operators within their borders. These operators can only exceed their allocations if they buy emission allowances, or offset their excesses through a mechanism that is agreed by all the parties to UNFCCC.

Annex II countries are a sub-group of the Annex I countries. They comprise the OECD members, excluding those that were economies in transition in 1992.

Developing countries are not required to reduce emission levels unless developed countries supply enough funding and technology. Setting no immediate restrictions under UNFCCC serves three purposes:

- it avoids restrictions on their development, because emissions are strongly linked to industrial capacity

- they can sell emissions credits to nations whose operators have difficulty meeting their emissions targets

- they get money and technologies for low-carbon investments from Annex II countries.

Developing countries may volunteer to become Annex I countries when they are sufficiently developed. Some opponents of the Convention argue that the split between Annex I and developing countries is unfair, and that both developing countries and developed countries need to reduce their emissions unilaterally. Some countries claim that their costs of following the Convention requirements will stress their economy. Other countries point to research, such as the Stern Report, that calculates the cost of compliance to be less than the cost of the consequences of doing nothing.

Annex I countries

There are 41 Annex I countries and the European Union is also a member. These countries are classified as industrialized countries and countries in transition:

Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia,Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden,Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States of America

Annex II countries

There are 23 Annex II countries and the European Union. Turkey was removed from the Annex II list in 2001 at its request to recognize its economy as a transition economy. These countries are classified as developed countries which pay for costs of developing countries:

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway,Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States of America Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was opened for signature at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) inRio de Janeiro (known by its popular title, the Earth Summit). On June 12, 1992, 154 nations signed the UNFCCC, that upon ratification committed signatories’ governments to a voluntary “non-binding aim” to reduce atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases with the goal of “preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth’s climate system.” These actions were aimed primarily at industrialized countries, with the intention of stabilizing their emissions of greenhouse gases at 1990 levels by the year 2000; and other responsibilities would be incumbent upon all UNFCCC parties. The parties agreed in general that they would recognize “common but differentiated responsibilities,” with greater responsibility for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the near term on the part of developed/industrialized countries, which were listed and identified in Annex I of the UNFCCC and thereafter referred to as “Annex I” countries.

Benchmarking

In the context of the UNFCCC, benchmarking is the setting of emission reduction commitments measured against a particular base year. The only quantified target set in the original FCCC (Article 4) was for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000. There are issues with benchmarking that can make it potentially inequitable. For example, take two countries that have identical emission reduction commitments as measured against the 1990 base year. This might be interpreted as being equitable, but this is not necessarily the case. One country might have previously made efforts to improve energy efficiency in the years preceding the benchmark year, while the other country had not. In economic terms, the marginal cost curve for emissions reductions rises steeply beyond a certain point. Thus, to meet its emission reduction commitment, the country with initially high energy efficiency might face high costs. But for the country that had previously encouraged over-consumption of energy, through subsidies, the costs of meeting its commitment would potentially be lower.

Precautionary principle

In decision making, the precautionary principle is considered when possibly dangerous, irreversible, or catastrophic events are identified, but scientific evaluation of the potential damage is not sufficiently certain. The precautionary principle implies an emphasis on the need to prevent such adverse effects.

Uncertainty is associated with each link of the causal chain of climate change. For example, future GHG emissions are uncertain, as are climate change damages. However, following the precautionary principle, uncertainty is not a reason for inaction, and this is acknowledged in Article 3.3 of the UNFCCC.

Interpreting Article

The ultimate objective of the Framework Convention is to prevent “dangerous” anthropogenic (i.e., human) interference of the climate system. As is stated in Article 2 of the Convention, this requires that GHG concentrations are stabilized in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, andeconomic development can proceed in a sustainable fashion.

Human activities have had a number of effects on the climate system. Global GHG emissions due to human activities have grown since pre-industrial times.Warming of the climate system has been observed, as indicated by increases in average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice cover, and rising global average sea level. As assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “[most] of the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic GHG concentrations. Very likely” here is defined by the IPCC as having a likelihood of greater than 90%, based on expert judgement.

The future levels of GHG emissions are highly uncertain.In 2010, the United Nations Enivronment Programme (UNEP) published a report on the voluntary emissions reduction pledges made as part of the Copenhagen Accord. As part of their assessment, UNEP looked at possible emissions out until the end of the 21st century, and estimated associated changes in global mean temperature. A range of emissions projections suggested a temperature increase of between 2.5 to 5 ºC before the end of the 21st century, relative to pre-industrial temperature levels. The lower end temperature estimate is associated with fairly stringent controls on emissions after 2020, while the higher end is associated with weaker controls on emissions.

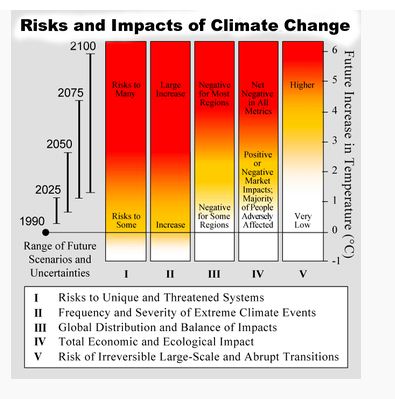

Graphical description of risks and impacts of climate change by the IPCC, published in 2001. A revision of this figure by Smith and others shows increased risks.

Graphical description of risks and impacts of climate change by the IPCC, published in 2001. A revision of this figure by Smith and others shows increased risks.

Future climate change will have a range of beneficial and adverse effects on human society and the environment. The larger the changes in climate, the more adverse effects are expected to predominate (see effects of global warming for more details).The IPCC has informed the UNFCCC process in determining what constitutes “dangerous” human interference of the climate system. Their conclusion is that such a determination involves value judgements, and will vary among different regions of the world. The IPCC has broken down current and future impacts of climate change into a range of “key vulnerabilities,” e.g., impacts affecting food supply, as well as five “reasons for concern,” shown opposite.

Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations

See also: climate change mitigation.

In order to stabilize the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere, emissions would need to peak and decline thereafter. The lower the stabilization level, the more quickly this peak and decline would need to occur. The emissions associated with atmospheric stabilization varies among different GHGs. This is because of differences in the processes that remove each gas from the atmosphere. Concentrations of some GHGs decrease almost immediately in response to emission reduction, e.g., methane, while others continue to increase for centuries even with reduced emissions, e.g., carbon dioxide.

All relevant GHGs need to be considered if atmospheric GHG concentrations are to be stabilized. Human activities result in the emission of four principal GHGs: carbon dioxide (chemical formula: CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide(N2O) and the halocarbons (a group of gases containing fluorine, chlorine and bromine). Carbon dioxide is the most important of the GHGs that human activities release into the atmosphere. At present, human activities are adding emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere far faster than they are being removed. This is analogous to a flow of water into a bathtub. So long as the tap runs water (analogous to the emission of carbon dioxide) into the tub faster than water escapes through the plughole (the natural removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere), then the level of water in the tub (analogous to the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere) will continue to rise. To stabilize the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide at a constant level, emissions would essentially need to be completely eliminated. It is estimated that reducing carbon dioxide emissions 100% below their present level (i.e., complete elimination) would lead to a slow decrease in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 by 40 parts-per-million (ppm) over the 21stcentury.

The emissions reductions required to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of CO2 can be contrasted with the reductions required for methane. Unlike CO2, methane has a well-definedlifetime in the atmosphere of about 12 years. Lifetime is defined as the time required to reduce a given perturbation of methane in the atmosphere to 37% of its initial amount. Stabilizing emissions of methane would lead, within decades, to a stabilization in its atmospheric concentration.

The climate system would take time to respond to a stabilization in the atmospheric concentration of CO2.Temperature stabilization would be expected within a few centuries. Sea level rise due thermal expansion would be expected to continue for centuries to millennia. Additional sea level rise due to ice melting would be expected to continue for several millennia. Conferences of the Parties Since the UNFCCC entered into force, the parties have been meeting annually in Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. From 2005 the Conferences have met in conjunction with Meetings of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (MOP), and parties to the Convention that are not parties to the Protocol can participate in Protocol-related meetings as observers.

1995 – COP 1, The Berlin Mandate

The first UNFCCC Conference of Parties took place in March 1995 in Berlin, Germany. It voiced concerns about the adequacy of countries’ abilities to meet commitments under the Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI).

1996 – COP 2, Geneva, Switzerland

COP 2 took place in July 1996 in Geneva, Switzerland. Its Ministerial Declaration was noted (but not adopted) July 18, 1996, and reflected a U.S. position statement presented byTimothy Wirth, former Under Secretary for Global Affairs for the U.S. State Department at that meeting, which

- Accepted the scientific findings on climate change proffered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its second assessment (1995);

- Rejected uniform “harmonized policies” in favor of flexibility;

- Called for “legally binding mid-term targets.”

The Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change

COP 3 took place in December 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. After intensive negotiations, it adopted the Kyoto Protocol, which outlined the greenhouse gas emissions reduction obligation for Annex I countries, along with what came to be known as Kyoto mechanisms such as emissions trading, clean development mechanism and joint implementation. Most industrialized countries and some central European economies in transition (all defined as Annex B countries) agreed to legally binding reductions in greenhouse gas emissions of an average of 6 to 8% below 1990 levels between the years 2008–2012, defined as the first emissions budget period. The United States would be required to reduce its total emissions an average of 7% below 1990 levels; however Congress did not ratify the treaty after Clinton signed it. The Bush administration explicitly rejected the protocol in 2001.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

COP 4 took place in November 1998 in Buenos Aires. It had been expected that the remaining issues unresolved in Kyoto would be finalized at this meeting. However, the complexity and difficulty of finding agreement on these issues proved insurmountable, and instead the parties adopted a 2-year “Plan of Action” to advance efforts and to devise mechanisms for implementing the Kyoto Protocol, to be completed by 2000. During COP4, Argentina and Kazakhstan expressed their commitment to take on the greenhouse gas emissions reduction obligation, the first two non-Annex countries to do so.

Bonn, Germany

COP 5 took place between October 25 and November 5, 1999, in Bonn, Germany. It was primarily a technical meeting, and did not reach major conclusions.

The Hague, Netherlands

COP 6 took place between November 13, – November 25, 2000, in The Hague, Netherlands. The discussions evolved rapidly into a high-level negotiation over the major political issues. These included major controversy over the United States’ proposal to allow credit for carbon “sinks” in forests and agricultural lands, satisfying a major proportion of the U.S. emissions reductions in this way; disagreements over consequences for non-compliance by countries that did not meet their emission reduction targets; and difficulties in resolving how developing countries could obtain financial assistance to deal with adverse effects of climate change and meet their obligations to plan for measuring and possibly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In the final hours of COP 6, despite some compromises agreed between the United States and some EU countries, notably the United Kingdom, the EU countries as a whole, led by Denmark and Germany, rejected the compromise positions, and the talks in The Hague collapsed. Jan Pronk, the President of COP 6, suspended COP-6 without agreement, with the expectation that negotiations would later resume. It was later announced that the COP 6 meetings (termed “COP 6 bis”) would be resumed in Bonn, Germany, in the second half of July. The next regularly scheduled meeting of the parties to the UNFCCC – COP 7 – had been set for Marrakech, Morocco, in October–November 2001.

COP 6 bis, Bonn, Germany

COP 6 negotiations resumed July 17–27, 2001, in Bonn, Germany, with little progress having been made in resolving the differences that had produced an impasse in The Hague. However, this meeting took place after George W. Bush had become the President of the United States and had rejected the Kyoto Protocol in March 2001; as a result the United States delegation to this meeting declined to participate in the negotiations related to the Protocol and chose to take the role of observer at the meeting. As the other parties negotiated the key issues, agreement was reached on most of the major political issues, to the surprise of most observers, given the low expectations that preceded the meeting. The agreements included:

- Flexible Mechanisms: The “flexibility” mechanisms which the United States had strongly favored when the Protocol was initially put together, including emissions trading; Joint Implementation (JI); and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) which allow industrialized countries to fund emissions reduction activities in developing countries as an alternative to domestic emission reductions. One of the key elements of this agreement was that there would be no quantitative limit on the credit a country could claim from use of these mechanisms provided domestic action constituted a significant element of the efforts of each Annex B country to meet their targets.

- Carbon sinks: It was agreed that credit would be granted for broad activities that absorb carbon from the atmosphere or store it, including forest and cropland management, and re-vegetation, with no over-all cap on the amount of credit that a country could claim for sinks activities. In the case of forest management, an Appendix Z establishes country-specific caps for each Annex I country. Thus, a cap of 13 million tons could be credited to Japan (which represents about 4% of its base-year emissions). For cropland management, countries could receive credit only for carbon sequestration increases above 1990 levels.

- Compliance: Final action on compliance procedures and mechanisms that would address non-compliance with Protocol provisions was deferred to COP 7, but included broad outlines of consequences for failing to meet emissions targets that would include a requirement to “make up” shortfalls at 1.3 tons to 1, suspension of the right to sell credits for surplus emissions reductions, and a required compliance action plan for those not meeting their targets.

- Financing: There was agreement on the establishment of three new funds to provide assistance for needs associated with climate change: (1) a fund for climate change that supports a series of climate measures; (2) a least-developed-country fund to support National Adaptation Programs of Action; and (3) a Kyoto Protocol adaptation fund supported by a CDM levy and voluntary contributions.

A number of operational details attendant upon these decisions remained to be negotiated and agreed upon, and these were the major issues considered by the COP 7 meeting that followed.

Marrakech, Morocco

At the COP 7 meeting in Marrakech, Morocco from October 29 to November 10, 2001, negotiators wrapped up the work on the Buenos Aires Plan of Action, finalizing most of the operational details and setting the stage for nations to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.deadlink[dead link] deadlink[dead link] The completed package of decisions is known as the Marrakech Accords. The United States delegation maintained its observer role, declining to participate actively in the negotiations. Other parties continued to express hope that the United States would re-engage in the process at some point and worked to achieve ratification of the Kyoto Protocol by the requisite number of countries to bring it into force (55 countries needed to ratify it, including those accounting for 55% of developed-country emissions of carbon dioxide in 1990). The date of the World Summit on Sustainable Development (August–September 2002) was put forward as a target to bring the Kyoto Protocol into force. The World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) was to be held in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The main decisions at COP 7 included:

- Operational rules for international emissions trading among parties to the Protocol and for the CDM and joint implementation;

- A compliance regime that outlined consequences for failure to meet emissions targets but deferred to the parties to the Protocol, once it came into force, the decision on whether those consequences would be legally binding;

- Accounting procedures for the flexibility mechanisms;

- A decision to consider at COP 8 how to achieve a review of the adequacy of commitments that might lead to discussions on future commitments by developing countries.

New Delhi, India

Taking place from October 23, – November 1, 2002, COP8 adopted the Delhi Ministerial Declaration that, amongst others, called for efforts by developed countries to transfer technology and minimize the impact of climate change on developing countries. It is also approved the New Delhi work programme on Article 6 of the Convention. The COP8 was marked by Russia’s hesitation, stating that the government needs more time to think it over. The Kyoto Protocol’s fine print says it can come into force only once it is ratified by 55 countries, including wealthy nations responsible for 55 per cent of the developed world’s 1990 carbon dioxide emissions. With the United States — and its 36.1 per cent slice of developed-world carbon dioxide — out of the picture and Australia also refusing ratification, Russia was required to make up the difference, hence it could delay the process.

Milan, Italy

The parties agreed to use the Adaptation Fund established at COP7 in 2001 primarily in supporting developing countries better adapt to climate change. The fund would also be used for capacity-building through technology transfer. At COP9, the parties also agreed to review the first national reports submitted by 110 non-Annex I countries.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Not to be confused with Convention on Biological Diversity, also called COP 10 (10th Conference of Parties) leading to the Nagoya Protocol in 2010.

See also Climate ethics: The Program on the Ethical Dimensions of Climate Change COP10 discussed the progress made since the first Conference of the Parties 10 years ago and its future challenges, with special emphasis on climate change mitigation and adaptation. To promote developing countries better adapt to climate change, the Buenos Aires Plan of Action was adopted. The parties also began discussing the post-Kyoto mechanism, on how to allocate emission reduction obligation following 2012, when the first commitment period ends.

Montreal, Canada

COP 11 (or COP 11/MOP 1) took place between November 28 and December 9, 2005, in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It was the first Meeting of the Parties (MOP-1) to the Kyoto Protocol since their initial meeting in Kyoto in 1997. It was therefore one of the largest intergovernmental conferences on climate change ever. The event marked the entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol. Hosting more than 10,000 delegates, it was one of Canada’s largest international events ever and the largest gathering in Montreal since. The Montreal Action Plan is an agreement hammered out at the end of the conference to “extend the life of the Kyoto Protocol beyond its 2012 expiration date and negotiate deeper cuts in greenhouse-gas emissions. Canada’s environment minister, at the time, Stéphane Dion, said the agreement provides a “map for the future.

See also COP 11 pages at the UNFCCC.

Nairobi, Kenya

COP 12/MOP 2 took place between November 6 and 17, 2006 in Nairobi, Kenya. At the meeting, BBC reporter Richard Black coined the phrase “climate tourists” to describe some delegates who attended “to see Africa, take snaps of the wildlife, the poor, dying African children and women”. Black also noted that due to delegates concerns over economic costs and possible losses of competitiveness, the majority of the discussions avoided any mention of reducing emissions. Black concluded that was a disconnect between the political process and the scientific imperative. Despite such criticism, certain strides were made at COP12, including in the areas of support for developing countries and clean development mechanism. The parties adopted a five-year plan of work to support climate change adaptation by developing countries, and agreed on the procedures and modalities for the Adaptation Fund. They also agreed to improve the projects for clean development mechanism.

Bali, Indonesia

Main article: 2007 United Nations Climate Change Conference

COP 13/MOP 3 took place between December 3 and December 15, 2007, at Nusa Dua, in Bali, Indonesia. Agreement on a timeline and structured negotiation on the post-2012 framework (the end of the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol) was achieved with the adoption of the Bali Action Plan (Decision 1/CP.13). The Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (AWG-LCA) was established as a new subsidiary body to conduct the negotiations aimed at urgently enhancing the implementation of the Convention up to and beyond 2012. Decision 9/CP.13 is an Amended to the New Delhi work programme. These negotiations took place during 2008 (leading to COP 14/MOP 4 in Poznan, Poland) and 2009 (leading to COP 15/MOP 5 in Copenhagen).

Poznań, Poland

Main article: 2008 United Nations Climate Change Conference

2008 United Nations Climate Change Conference COP 14 in Poznan. More image and news: 2008 United Nations Climate Change Conference

COP/MOP 4 took place from December 1 to12, 2008 in Poznań, Poland. Delegates agreed on principles for the financing of a fund to help the poorest nations cope with the effects of climate change and they approved a mechanism to incorporate forest protection into the efforts of the international community to combat climate change.

Copenhagen, Denmark

Main article: 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference

COP/ took place in Copenhagen, Denmark, from December 7 to December 18, 2009.

The overall goal for the COP 15/MOP 5 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Denmark was to establish an ambitious global climate agreement for the period from 2012 when the first commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol expires. However, on November 14, 2009, theNew York Times announced that “President Obama and other world leaders have decided to put off the difficult task of reaching a climate change agreement… agreeing instead to make it the mission of the Copenhagen conference to reach a less specific “politically binding” agreement that would punt the most difficult issues into the future. Ministers and officials from 192 countries took part in the Copenhagen meeting and in addition there were participants from a large number of civil society organizations. As many Annex 1 industrialized countries are now reluctant to fulfill commitments under the Kyoto Protocol, a large part of the diplomatic work that lays the foundation for a post-Kyoto agreement was undertaken up to the COP15.

The conference did not achieve a binding agreement for long-term action. A 13-paragraph ‘political accord’ was negotiated by approximately 25 parties including US and China, but it was only ‘noted’ by the COP as it is considered an external document, not negotiated within the UNFCCC process. The accord was notable in that it referred to a collective commitment by developed countries for new and additional resources, including forestry and investments through international institutions, that will approach USD 30 billion for the period 2010–2012. Longer-term options on climate financing mentioned in the accord are being discussed within the UN Secretary General’s High Level Advisory Group on Climate Financing, which is due to report in November 2010. The negotiations on extending the Kyoto Protocol had unresolved issues as did the negotiations on a framework for long-term cooperative action. The working groups on these tracks to the negotiations are now due to report to COP 16 and MOP 6 in Mexico.

Cancún, Mexico

Main article: 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference

COP 16 was held in Cancún, Mexico, from November 29 to December 10, 2010.

Durban, South Africa

The 2011 COP is to be hosted by Durban, South Africa, from November 28 to December 9, 2011. Two countries, Qatar and South Korea, are currently bidding to host the 2012 COP 18.

Subsidiary bodies

A subsidiary body is a committee that assists the Conference of the Parties. Subsidiary bodies includes:

- Permanents:

- The Subsidiary Board of Implementation (SBI) makes recommendations on policy and implementation issues to the COP and, if requested, to other bodies.

- The Subsidiary Board of Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) serves as a link between information and assessments provided by expert sources (such as the IPCC) and the COP, which focuses on setting policy.

- Temporary:

- AWG-LCA

- AWG-KP

Secretariat

The work under the UNFCCC is facilitated by a secretariat in Bonn, Germany, which from July 2010 is headed by Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres.

UNFCCC members

1. Afghanistan

2. Albania

3. Algeria

4. Angola

5. Antigua and Barbuda

6. Argentina

7. Armenia

8. Australia

9. Austria

10. Azerbaijan

11. Bahamas

12. Bahrain

13. Bangladesh

14. Barbados

15. Belarus

16. Belgium

17. Belize

18. Benin

19. Bhutan

20. Bolivia

21. Bosnia and Herzegovina

22. Botswana

23. Brazil

24. Brunei

25. Bulgaria

26. Burkina Faso

27. Myanmar

28. Burundi

29. Cambodia

30. Cameroon

31. Canada

32. Cape Verde

33. Central African Republic

34. Chad

35. Chile

36. China

37. Colombia

38. Comoros

39. Democratic Republic of the Congo

40. Republic of the Congo

41. Cook Islands

42. Costa Rica

43. Côte d’Ivoire

44. Croatia

45. Cuba

46. Cyprus

47. Czech Republic

48. Denmark

49. Djibouti

50. Dominica

51. Dominican Republic

52. Ecuador

53. Egypt

54. El Salvador

55. Equatorial Guinea

56. Eritrea

57. Estonia

58. Ethiopia

59. European Union

60. Fiji

61. Finland

62. France

63. Gabon

64. Gambia

65. Georgia

66. Germany

67. Ghana

68. Greece

69. Grenada

70. Guatemala

71. Guinea

72. Guinea-Bissau

73. Guyana

74. Haiti

75. Honduras

76. Hungary

77. Iceland

78. India

79. Indonesia

80. Iran

81. Iraq

82. Ireland

83. Israel

84. Italy

85. Jamaica

86. Japan

87. Jordan

88. Kazakhstan

89. Kenya

90. Kiribati

91. North Korea

92. South Korea

93. Kuwait

94. Kyrgyzstan

95. Laos

96. Latvia

97. Lebanon

98. Lesotho

99. Liberia

100. Libya

101. Liechtenstein

102. Lithuania

103. Luxembourg

104. Republic of Macedonia

105. Madagascar

106. Malawi

107. Malaysia

108. Maldives

109. Mali

110. Malta

111. Marshall Islands

112. Mauritania

113. Mauritius

114. Mexico

115. Federated States of Micronesia

116. Moldova

117. Monaco

118. Mongolia

119. Montenegro

120. Morocco

121. Mozambique

122. Namibia

123. Nauru

124. Nepal

125. Netherlands

126. New Zealand

127. Nicaragua

128. Niger

129. Nigeria

130. Niue

131. Norway

132. Oman

133. Pakistan

134. Palau

135. Panama

136. Papua New Guinea

137. Paraguay

138. Peru

139. Philippines

140. Poland

141. Portugal

142. Qatar

143. Romania

144. Russia

145. Rwanda

146. Saint Kitts and Nevis

147. Saint Lucia

148. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

149. Samoa

150. San Marino

151. Sao Tome and Principe

152. Saudi Arabia

153. Senegal

154. Serbia

155. Seychelles

156. Sierra Leone

157. Singapore

158. Slovakia

159. Slovenia

160. Solomon Islands

161. Somalia

162. South Africa

163. Spain

164. Sri Lanka

165. Sudan

166. Suriname

167. Swaziland

168. Sweden

169. Switzerland

170. Syria

171. Tajikistan

172. Tanzania

173. Thailand

174. Timor-Leste

175. Togo

176. Tonga

177. Trinidad and Tobago

178. Tunisia

179. Turkey

180. Turkmenistan

181. Tuvalu

182. Uganda

183. Ukraine

184. United Arab Emirates

185. United Kingdom

186. United States

187. Uruguay

188. Uzbekistan

189. Vanuatu

190. Venezuela

191. Vietnam

192. Yemen

193. Zambia

194. Zimbabwe

1. Andorra

2. Holy See

See also

Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS)

Avoiding Dangerous Climate Change an international conference

Climate Change Information Network (CC:iNet)

Climate ethics

Coalition for Rainforest Nations

Greenhouse Mafia Australia’s carbon lobby

Individual and political action on climate change Climate change response

Least Developed Country (LDC)

List of international environmental agreements

Montreal Protocol

Post–Kyoto Protocol negotiations on greenhouse gas emissions

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)

United Nations Regional Groups including African Group

World People’s Conference on Climate Change

External links

- Official site of the UNFCCC

- Text of the UNFCCC as a PDF

- Text of the UNFCCC as HTML

- The Framework Convention on Climate Change at Law-Ref.org — fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

- Glossary

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin — detailed summaries of all COPs and SBs

- Party Groupings

- Caring for Climate

- Denmark’s Host Country Website for COP15

- COP15 on China Development Gateway

- Live interactive video and chat coverage of COP16

View page ratings

Rate this page

What’s this?

Trustworthy

Objective

Complete

Well-written

I am highly knowledgeable about this topic (optional)

Submit ratings

Categories: Carbon finance | Climate change policy | Environment treaties | Environmental economics | Greenhouse gas inventories | Treaties concluded in 1992 | Treaties entered into force in 1994 | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Chan

Notes toward an International Libertarian Eco-Socialism youth protests and further reports from Klimaforum10 The specter of tragedy and Klimaforum

By intlibecosoc

NB: Also published on Climate & Capitalism

The second day of the sixteenth Conference of Parties (COP-16) summit in Cancún follows much the same as the first, a day that saw Mexican President Felipe Calderón assert in remarks before the delegates assembled in Moon Palace—a highly exclusive hotel, center of the COP-16 talks—that the potential failure of the Cancún talks—that is, their failure precisely to look beyond dominant individual and national interests—would be a “tragedy,” and that climate-negotiators should act during the summit’s two weeks with the interests of humanity in mind. He stressed in particular the concern that should be evinced in Cancún for existing children and future generations. In his address to delegates on the same day, Mario Molina, a Mexican scientist awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995, declared it to be “necessary and urgent” that COP-16 produce a climate-agreement—this, amidst a widespread lack of confidence among country-governments and commentators that Cancún will produce any agreement at all.

As was the case on Monday, COP-16’s second day saw dozens of members of international organization “Ching Hai SOS,” a branch of the Supreme Master Ching Hai International Association, protesting outside the Cancunmesse, a conference center that has been set aside as one of COP-16’s halls of negotiation. The SOS protestors, present outside the Cancumesse throughout the day since the early morning, advocate the general adoption of an organic-vegan diet, claiming such a move to be essential to “save the planet.” They also rather bizarrely maintain such diets to produce good karma, and are likely mistaken in arguing for such a singular solution to the specter of climate catastrophe—the stress on diet seems to overlook the rather pressing issue of capitalism, for example.

In an attempt to spread its message, the SOS has bought advertising space on billboards and taxi in parts of Cancún; this marketing-strategy has also taken up by Greenpeace, which has purchased advertisements on buses in addition to billboards in the city that remind observers of the recent disastrous experience with the Gulf of Mexico oil spill as a reason to abolish the use of petroleum—reason, that is, beyond petroleum’s inescapable contributions to dangerous anthropogenic interference with the Earth’s climate systems.

It seems that no protests other than that carried out by the SOS were had in Cancún today.

The present author visited Klimaforum10’s campus today. Klimaforum10, the successor of last year’s Klimaforum09 held during COP-15 in Copenhagen, is being held at the El Rey Polo Country Club, itself located a number of kilometers from Puerto Morales, a city some 40 kilometers south of Cancún. Klimaforum10 has installed itself on a pasture within the confines of the country club; it is made up of a number of tents at which workshops, discussions, and film-screenings are had. A number of the events planned to take place at Klimaforum10—a discussion on climate and human conflict; a presentation on the status and possible fate of the ‘Third Pole,’ or the glaciers to be found in the Tibetan highlands; remarks by Polly Higgins, advocate of the introduction of the crime of ecocide into international law; a speech on the impacts on indigenous peoples of glacier-retreat in the Andes; a workshop on the importance of the place of commons in place of statist and private-property regimes; popular reflections on the question of science and responsibility; a panel on the rights of climate-migrants—seem rather compelling, but the location and ethos that seemed there to prevail—one of lifestylism—proved rather disconcerting.

The six Via Campesina caravans that are currently touring various sites in Mexico to highlight the very real damage climate change has to date had on the country—evident above all in the unprecedented rains and floods suffered this year in the country’s south—are expected to arrive in Cancún on either 2 or 3 December, so as to be present for the beginning of the Meeting “For Life and Environmental and Social Justice” on 4 December. In addition to the mass-protest planned for 7 December, Via Campesina is also organizing a march “For Life and Climate Justice” for 5 December. The Espacio Mexicano-Diálogo Climático (Mexican Space for Climate Dialogue, or EsMex), another counter-summit to the COP-16, is currently setting-up its installations in downtown Cancún; the space is to be provided solar energy from a Greenpeace truck, the “Sunflower.”

Today it was revealed that neither Brazilian President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva nor British Prime Minister David Cameron plan to attend the COP-16 talks at all. In contrast, and in accordance with government-representative José Crespo Fernández, Bolivian President Evo Morales is slated to arrive in Cancún on 9 December, when he is expected to present a speech to international civil society. Though the U.S. plans to send Secretary of Energy Steven Chu to the talks, it still remains unclear whether U.S. president Barack Obama will deign COP-16 with his presence.

The wind power-generator inaugurated by Calderón on the eve of the summit’s opening, located in an air corridor between Cancún and the Cancunmesse, has been denounced in recent days as having failed to meet governmental environmental standards during its construction. Its fate is unclear, but the installation—purportedly erected so as to provide electricity for COP-16—may well have to be removed following the end of the conference, in accordance with existing regulations.

With regard to the state of repressive statist forces in Cancún, the Mexican police and military continue in full force, deployed at several sites in the city and its environs and continuing their patrols. It seems that the federal government has rented from Israel an unmanned aerial vehicle for use in Cancún; it is claimed that the drone will be employed for the monitoring of traffic both vehicular and human in the area.

This entry was posted on December 1, 2010 at 5:15 am and is filed under ‘development’,Abya Yala, climate catastrophe, COP, imperialism, México, Palestine, reformism. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

KKL-JNF at COP16

By KKL – JNF

Israeli Delegation Presents Ways of Adapting to Climate Change at Cancun Climate Conference

As part of the events that took place at the UN Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico, the Israeli delegation held a side event that addressed the various ways of adapting to life in arid regions. KKL-JNF initiated the side event together with the government of Israel in order to present and share the knowledge Israel has acquired on adapting to hot and arid climates. The event was moderated by Dr. Orr Karassin, head of the KKL-JNF delegation to the conference, who emphasized that the purpose of the side event was not to debate policy, as was the case at most of the conference discussions, but rather to present practical solutions in the fields of agriculture and afforestation in hot and arid regions: “In spite of the different topics of the lectures that were presented at the side event, they have a shared motif, which is the challenges and practical solutions that were implemented in Israel for life on

that in an era of global warming, increasingly more countries will have to learn how to farm and prevent damage to the environment in hot and arid conditions. It is our hope that some of the knowledge that we have already acquired in Israel will be useful for the rest of the world. It is clear that there is still a long road in front of us.

“In Israel, we need to better study the ramifications of climate change for our region, and the effects of our ways of dealing with it. The Carmel forest fire was a terrifying reminder of this necessity. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges the state of Israel and other countries have ever faced. I will make every effort to ensure that KKL-JNF’s research department will devote itself to investigating the ramifications of climate change on Israel’s forests and to the ways of protecting forests in an era of global warming and changes in annual rainfall.”

The first lecture was by Mr. Itzik Moshe, deputy director of KKL-JNF’s Southern Region, on desert afforestation and agriculture in semi-arid and arid regions. Itzik presented the methods developed by KKL-JNF, including harvesting runoff water and planting species that can survive in harsh climatic conditions. Itzik answered the many questions that the audience asked regarding the amount of rainfall necessary to grow trees and the effects of harvesting runoff water, which has a positive effect on preventing floods and erosion in those regions that have a tendency for damage to land quality. Itzik emphasized that Israel’s unprecedented success in foresting areas with an average of 250-350 mms. of average rainfall is based on ancient methods that were used by local inhabitants for hundreds of years: “Actually, there is not too much that is new in our forestry methods. All we are doing is combining ancient knowledge with modern tools. The methods developed in Israel could instigate a revolution in semi-arid regions. KKL-JNF is eager to share its expertise with countries throughout the world.”

The next lecture was presented by Dr. Gabi Adin, director of the Cattle Raising Department of the Ministry of Agriculture. Dr. Adin described Israel’s success in raising dairy cows that produce the highest average yield in the world, approximately 11,000 liters per year, far exceeding the European average of about 8,000 liters annually. There are, however, claims that raising cattle for dairy and meat are the cause of about 30% of global warming, due to energy outputs and the methane emissions of the cows. According to Dr. Adin, besides the commercial advantage of the Israeli dairy cow, this cow also has an ecological advantage, since it emits less methane gas per liter of milk.

The concluding speaker at the KKL-JNF side-event was Dr. Alon Ben-Gal, an expert on irrigation from the Volcani Institure, who spoke on irrigation in arid regions where various crops are grown, including dates and olives. Dr. Ben-Gal emphasized the benefits of drip irrigation as a means of enabling people to make a livelihood in these regions, without which it would be impossible for them to inhabit them. People in the audience asked about the use of brackish water for irrigation, questioning whether it wouldn’t cause salification of the land which would render it unusable for farming, as was the case in Australia. Dr. Ben Gal answered that this was in fact a problem, and that so far, Israeli farmers in the Arava had been lucky, since irrigation water penetrates the Arava soil, preventing salification. “For this reason,” Dr. Ben Gal concluded, “the answers and solutions that future research will provide are critical for enabling Israel to continue farming the Negev desert and to continue taking advantage of the local aquifer, which has copious amounts of brackish water.”

COP 16 in Cancun, Mexico

Alberta is attending the 16th annual United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP16) on climate change in Cancun, Mexico to support an achievable, fair and comprehensive agreement.

“The world must find solutions to the challenge of meeting a growing global energy demand, retaining economic growth and reducing emissions. While climate change is the focus in Cancun, others will want to hear about the environmental performance of our oil sands. I will take this opportunity to talk about Alberta’s challenges, successes and the importance of our energy resource to all Canadians. We have a record to be proud of and an important story to tell.”

-Minister of Environment Rob Renner, head of Alberta’s delegation in Cancun

Read Minister Renner’s statement (December 2, 2010)

Read the News Release

Continue on to Alberta’s Climate

Cancun Summit (COP16)

- Reduce Your Carbon Footprint

- Resources

- Share Your Solutions

- Green Your School

Background to World Climate Negotiations

In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s leading scientists from around the world introduced research findings that clearly showed a correlation between a rise in global greenhouse gas emissions, manmade and otherwise, and a rise in global temperatures.

The IPCC was established to provide the decision-makers and others interested in climate change with an objective source of information about climate change. The IPCC is a scientific intergovernmental body set up by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In 2007 the IPCC received the Nobel Peace Prize.

The IPCC findings were brought to the attention of world leaders who participated in the first UN Framework Convention on Climate Change held in Rio de Janeiro (frequently referred to as the “Rio Earth Summit”) in 1992.

Following the Rio Earth Summit, world leaders met again in Berlin, Germany in 1995 to make commitments to reduce their respective emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000. At this Summit, since referred to as the Berlin Summit, the Contracting Parties reviewed the commitments by the developed countries under the original convention adopted in Rio in 1992, and decided that the commitments aimed at returning their emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000 was inadequate for achieving the Convention’s long-term objective.

The Conference produced the “Berlin Mandate” and launched a new round of negotiations aimed at strengthening the commitments of the leaders from developed countries. The Berlin Summit was thought by some as “a great first step to achieving a global agreement on greenhouse gas emissions.” It was however deemed too soft by most parties, in addition to various nongovernmental organizations who attended the summit alongside world leaders, that referred to the agreement as a “soft mandate” — which failed to adopt specific reductions, including vague targets and terms such as “quantified limitation and reduction objectives” with time-frames “such as 2005, 2010 and 2020”. The definitions in the agreement were seen to be too weak, with no specific mention of percentage cuts to C02 emissions. The Kyoto Summit (1997, Kyoto, Japan)

At the third Conference of the world leaders in Kyoto, Japan in 1997, two years following the Berlin Summit, world leaders adopted the Kyoto Protocol. Undoubtedly the most easily recognizable of all the Summits held on the subject of climate change, the Kyoto Summit had the same ultimate objectives as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was the stabilization of atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. The Kyoto Summit added key points that many parties felt were not addressed in depth at the Berlin Summit such as setting what was deemed to be more “realistic” time-frames sufficient and necessary to ensure that food production is not threatened and that economic development can continue sustainably.

Key Provisions of the Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol is a 21 page document outlining various new commitments made by global parties. In it, Contracting Parties from developed countries are committed to reducing their combined greenhouse gas emissions by at least 5 per cent from 1990 levels by the period 2008-2012. The targets cover the six main greenhouse gases, namely, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), per fluorocarbons (PFCs) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), along with some activities in the land-use change and forestry sector that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (carbon “sinks”). Each Contracting Party from developed countries is required to have made demonstrable progress in implementing its emission reduction commitments by 2005.

The Kyoto Protocol also establishes three innovative mechanisms, known as joint implementation, emissions trading and the clean development mechanism, which are designed to help Contracting Parties included in Annex I of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to reduce the costs of meeting their emission targets. The clean development mechanism also aims to promote sustainable development in developing countries. The operational details of these mechanisms are now being fleshed out by the Contracting Parties.

The procedure for the communication and review of information is established in the Kyoto Protocol. Contracting Parties from developed countries are required to incorporate in their national communications the supplementary information necessary to demonstrate compliance with their commitments under the Protocol in accordance with guidelines to be developed. The information submitted shall be reviewed by expert review teams, pursuant to guidelines established by the Conference of the Parties, which is the supreme body that shall regularly review and promote effective implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol.

For an in depth look at the text, commitments, targets and history of the Kyoto Protocol, please visit:http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/tp/tp0200.pdf

Kyoto Protocol Milestone – Canadian Ratification

The Kyoto Protocol was the first international treaty on climate change that became international law. To take full effect, the Protocol required ratification by at least 55 members of the United Nations, which together were responsible for at least 55 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions in 1990.

In 2002 Canada became the 99th country to ratify the Kyoto Protocol for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This move on behalf of the government of then Canadian Prime Minister, Jean Chretien, set the stage for Russia to ratify the treaty and achieve critical mass. On November 5, 2004, the Kremlin announced that President Vladimir Putin had signed the federal law “on ratification of the Kyoto Protocol to the framework convention of the United Nations on climate change.” The protocol became legally binding on all participating countries 90 days after Russia notified the United Nations of its ratification.

Although this was a milestone, the pledges made by most countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels went unfulfilled. With no enforcement mechanism in place, and the unwillingness of the largest economy and producer of green house gases in the world, the United States, to sign on, the protocol went unfulfilled.

The Copenhagen Summit

In 2012 the Kyoto Protocol and the mandates included therein aimed at preventing climate change and global warming, expires. In order to ensure that reducing greenhouse gas production is kept a top priority for top leaders around the world, there is an urgent need for a new climate protocol. The Conference of Parties in Copenhagen (COP15) in 2009 was expected to be a milestone in the history of climate change mitigation, but world leaders failed to agree on tangible objectives, sufficient to curb climate change and ensure a sustainable future for our children. Canada and the United States pledged to reduce their emissions by 17% of their 2005 levels, by 2020. This target fell short of many other industrialized countries’ expectations, which pledge a higher percentage and an earlier base year – the most common being 1990.

The Cancun Summit

From November 29th to December 10th, 2010, Mexico will be hosting the next and highly anticipated international climate change conference in Cancun. It serves as the last opportunity for world leaders to agree to a new protocol aimed at curbing and limiting carbon emissions prior to the expiration of the Kyoto Protocol.

Summit Details

The conference in Cancun is the 16th conference of parties (COP16) in the Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Climate Conference will take place in the Moon Palace Hotel in the city of Cancun. Governmental representatives from over 170 countries are expected to be in attendance during the Summit accompanied by numerous nongovernmental representatives, NGOs, journalists and others. In total 8000 people are expected to descend upon Cancun in the days leading up to and during the Summit.

Get involved!

Talk to your elected representatives: Email your Member of Parliament and Jim Prentice, Canadian Minister of Environment, to communicate your concerns about climate change and ask that they take your future seriously. While you’re at it, email or call Prime Minister Stephen Harper too!

Stephen Harper, Prime Minister:

Harper.S@parl.gc.ca | Phone: 613.992.4211 (Hill office) and 403.253.7990 (Constituency office)

Jim Prentice, Minister of the Environment:

Prentice.J@parl.gc.ca | Phone 613.947.9475 (Hill office) and 413.216.7777 (Constituency office)

Members of Parliament: Their contact information can be found here:

http://webinfo.parl.gc.ca/MembersOfParliament/MainMPsCompleteList.aspx?TimePeriod=Current&Language=E

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC or FCCC) is an international environmental treaty produced at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro from June 3 to 14, 1992. The objective of the treaty is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.

The treaty itself set no mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions for individual countries and contains no enforcement mechanisms. In that sense, the treaty is considered legally non-binding. Instead, the treaty provides for updates (called “protocols”) that would set mandatory emission limits. The principal update is the Kyoto Protocol, which has become much better known than the UNFCCC itself.

The UNFCCC was opened for signature on May 9, 1992, after an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee produced the text of the Framework Convention as a report following its meeting in New York from April 30 to May 9, 1992. It entered into force on March 21, 1994. As of May 2011, UNFCCC has 194 parties.

One of its first tasks was to establish national greenhouse gas inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals, which were used to create the 1990 benchmark levels for accession of Annex I countries to the Kyoto Protocol and for the commitment of those countries to GHG reductions. Updated inventories must be regularly submitted by Annex I countries.

The UNFCCC is also the name of the United Nations Secretariat charged with supporting the operation of the Convention, with offices in Haus Carstanjen, Bonn, Germany. From 2006 to 2010 the head of the secretariat was Yvo de Boer; on May 17, 2010 his successor, Christiana Figueres from Costa Rica has been named. The Secretariat, augmented through the parallel efforts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), aims to gain consensus through meetings and the discussion of various strategies.

The parties to the convention have met annually from 1995 in Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was concluded and established legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Annex I, Annex II countries and developing countries

Parties to UNFCCC are classified as:

- Annex I countries – industrialized countries and economies in transition

- Annex II countries – developed countries which pay for costs of developing countries

- Non Annex I countries – Developing countries.

Annex I countries which have ratified the Protocol have committed to reduce their emission levels of greenhouse gasses to targets that are mainly set below their 1990 levels. They may do this by allocating reduced annual allowances to the major operators within their borders. These operators can only exceed their allocations if they buy emission allowances, or offset their excesses through a mechanism that is agreed by all the parties to UNFCCC.

Annex II countries are a sub-group of the Annex I countries. They comprise the OECD members, excluding those that were economies in transition in 1992.

Developing countries are not required to reduce emission levels unless developed countries supply enough funding and technology.

Setting no immediate restrictions under UNFCCC serves three purposes:

- it avoids restrictions on their development, because emissions are strongly linked to industrial capacity

- they can sell emissions credits to nations whose operators have difficulty meeting their emissions targets

- they get money and technologies for low-carbon investments from Annex II countries.

Developing countries may volunteer to become Annex I countries when they are sufficiently developed.

Some[specify] opponents of the Convention argue that the split between Annex I and developing countries is unfair, and that both developing countries and developed countries need to reduce their emissions unilaterally.[citation needed] Some[specify] countries claim that their costs of following the Convention requirements will stress their economy.[citation needed] Other countries[specify] point to research, such as the Stern Report, that calculates the cost of compliance to be less than the cost of the consequences of doing nothing.[citation needed]

Annex I countries

There are 41 Annex I countries and the European Union is also a member. These countries are classified as industrialized countries and countries in transition:

Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia,Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden,Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States of America

Annex II countries

There are 23 Annex II countries and the European Union. Turkey was removed from the Annex II list in 2001 at its request to recognize its economy as a transition economy. These countries are classified as developed countries which pay for costs of developing countries:

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway,Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States of America

U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was opened for signature at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) inRio de Janeiro (known by its popular title, the Earth Summit). On June 12, 1992, 154 nations signed the UNFCCC, that upon ratification committed signatories’ governments to a voluntary “non-binding aim” to reduce atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases with the goal of “preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth’s climate system.” These actions were aimed primarily at industrialized countries, with the intention of stabilizing their emissions of greenhouse gases at 1990 levels by the year 2000; and other responsibilities would be incumbent upon all UNFCCC parties. The parties agreed in general that they would recognize “common but differentiated responsibilities,” with greater responsibility for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the near term on the part of developed/industrialized countries, which were listed and identified in Annex I of the UNFCCC and thereafter referred to as “Annex I” countries.

Benchmarking

In the context of the UNFCCC, benchmarking is the setting of emission reduction commitments measured against a particular base year. The only quantified target set in the original FCCC (Article 4) was for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2000. There are issues with benchmarking that can make it potentially inequitable. For example, take two countries that have identical emission reduction commitments as measured against the 1990 base year. This might be interpreted as being equitable, but this is not necessarily the case. One country might have previously made efforts to improve energy efficiency in the years preceding the benchmark year, while the other country had not. In economic terms, the marginal cost curve for emissions reductions rises steeply beyond a certain point. Thus, to meet its emission reduction commitment, the country with initially high energy efficiency might face high costs. But for the country that had previously encouraged over-consumption of energy, e.g., through subsidies, the costs of meeting its commitment would potentially be lower.

Precautionary principle

In decision making, the precautionary principle is considered when possibly dangerous, irreversible, or catastrophic events are identified, but scientific evaluation of the potential damage is not sufficiently certain.The precautionary principle implies an emphasis on the need to prevent such adverse effects.

Uncertainty is associated with each link of the causal chain of climate change. For example, future GHG emissions are uncertain, as are climate change damages. However, following the precautionary principle, uncertainty is not a reason for inaction, and this is acknowledged in Article 3.3 of the UNFCCC.

Interpreting Article

The ultimate objective of the Framework Convention is to prevent “dangerous” anthropogenic (i.e., human) interference of the climate system. As is stated in Article 2 of the Convention, this requires that GHG concentrations are stabilized in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, andeconomic development can proceed in a sustainable fashion.

Human activities have had a number of effects on the climate system. Global GHG emissions due to human activities have grown since pre-industrial times. Warming of the climate system has been observed, as indicated by increases in average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice cover, and rising global average sea level. As assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “[most] of the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic GHG concentrations. Very likely” here is defined by the IPCC as having a likelihood of greater than 90%, based on expert judgement.

The future levels of GHG emissions are highly uncertain. In 2010, the United Nations Enivronment Programme (UNEP) published a report on the voluntary emissions reduction pledges made as part of the Copenhagen Accord. As part of their assessment, UNEP looked at possible emissions out until the end of the 21st century, and estimated associated changes in global mean temperature. A range of emissions projections suggested a temperature increase of between 2.5 to 5 ºC before the end of the 21st century, relative to pre-industrial temperature levels. The lower end temperature estimate is associated with fairly stringent controls on emissions after 2020, while the higher end is associated with weaker controls on emissions.

Graphical description of risks and impacts of climate change by the IPCC, published in 2001. A revision of this figure by Smith and others shows increased risks.

Future climate change will have a range of beneficial and adverse effects on human society and the environment. The larger the changes in climate, the more adverse effects are expected to predominate (see effects of global warming for more details). The IPCC has informed the UNFCCC process in determining what constitutes “dangerous” human interference of the climate system. Their conclusion is that such a determination involves value judgements, and will vary among different regions of the world. The IPCC has broken down current and future impacts of climate change into a range of “key vulnerabilities,” e.g., impacts affecting food supply, as well as five “reasons for concern,” shown opposite.

Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations

See also: climate change mitigation.

In order to stabilize the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere, emissions would need to peak and decline thereafter. The lower the stabilization level, the more quickly this peak and decline would need to occur. The emissions associated with atmospheric stabilization varies among different GHGs. This is because of differences in the processes that remove each gas from the atmosphere. Concentrations of some GHGs decrease almost immediately in response to emission reduction, e.g., methane, while others continue to increase for centuries even with reduced emissions, e.g., carbon dioxide.

All relevant GHGs need to be considered if atmospheric GHG concentrations are to be stabilized. Human activities result in the emission of four principal GHGs: carbon dioxide (chemical formula: CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide(N2O) and the halocarbons (a group of gases containing fluorine, chlorine and bromine).Carbon dioxide is the most important of the GHGs that human activities release into the atmosphere. At present, human activities are adding emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere far faster than they are being removed. This is analogous to a flow of water into a bathtub. So long as the tap runs water (analogous to the emission of carbon dioxide) into the tub faster than water escapes through the plughole (the natural removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere), then the level of water in the tub (analogous to the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere) will continue to rise. To stabilize the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide at a constant level, emissions would essentially need to be completely eliminated. It is estimated that reducing carbon dioxide emissions 100% below their present level (i.e., complete elimination) would lead to a slow decrease in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 by 40 parts-per-million (ppm) over the 21stcentury.

The emissions reductions required to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of CO2 can be contrasted with the reductions required for methane. Unlike CO2, methane has a well-definedlifetime in the atmosphere of about 12 years. Lifetime is defined as the time required to reduce a given perturbation of methane in the atmosphere to 37% of its initial amount. Stabilizing emissions of methane would lead, within decades, to a stabilization in its atmospheric concentration.

The climate system would take time to respond to a stabilization in the atmospheric concentration of CO2. Temperature stabilization would be expected within a few centuries. Sea level rise due thermal expansion would be expected to continue for centuries to millennia. Additional sea level rise due to ice melting would be expected to continue for several millennia.

Conferences of the Parties

Since the UNFCCC entered into force, the parties have been meeting annually in Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. From 2005 the Conferences have met in conjunction with Meetings of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (MOP), and parties to the Convention that are not parties to the Protocol can participate in Protocol-related meetings as observers. The Berlin Mandate

The first UNFCCC Conference of Parties took place in March 1995 in Berlin, Germany. It voiced concerns about the adequacy of countries’ abilities to meet commitments under the Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI).

Geneva, Switzerland

COP 2 took place in July 1996 in Geneva, Switzerland. Its Ministerial Declaration was noted (but not adopted) July 18, 1996, and reflected a U.S. position statement presented byTimothy Wirth, former Under Secretary for Global Affairs for the U.S. State Department at that meeting, which

- Accepted the scientific findings on climate change proffered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its second assessment (1995);

- Rejected uniform “harmonized policies” in favor of flexibility;

- Called for “legally binding mid-term targets.”

The Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change

COP 3 took place in December 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. After intensive negotiations, it adopted the Kyoto Protocol, which outlined the greenhouse gas emissions reduction obligation for Annex I countries, along with what came to be known as Kyoto mechanisms such as emissions trading, clean development mechanism and joint implementation. Most industrialized countries and some central European economies in transition (all defined as Annex B countries) agreed to legally binding reductions in greenhouse gas emissions of an average of 6 to 8% below 1990 levels between the years 2008–2012, defined as the first emissions budget period. The United States would be required to reduce its total emissions an average of 7% below 1990 levels; however Congress did not ratify the treaty after Clinton signed it. The Bush administration explicitly rejected the protocol in 2001.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

COP 4 took place in November 1998 in Buenos Aires. It had been expected that the remaining issues unresolved in Kyoto would be finalized at this meeting. However, the complexity and difficulty of finding agreement on these issues proved insurmountable, and instead the parties adopted a 2-year “Plan of Action” to advance efforts and to devise mechanisms for implementing the Kyoto Protocol, to be completed by 2000. During COP4, Argentina and Kazakhstan expressed their commitment to take on the greenhouse gas emissions reduction obligation, the first two non-Annex countries to do so.

Bonn, Germany

COP 5 took place between October 25 and November 5, 1999, in Bonn, Germany. It was primarily a technical meeting, and did not reach major conclusions.

The Hague, Netherlands

COP 6 took place between November 13, – November 25, 2000, in The Hague, Netherlands. The discussions evolved rapidly into a high-level negotiation over the major political issues. These included major controversy over the United States’ proposal to allow credit for carbon “sinks” in forests and agricultural lands, satisfying a major proportion of the U.S. emissions reductions in this way; disagreements over consequences for non-compliance by countries that did not meet their emission reduction targets; and difficulties in resolving how developing countries could obtain financial assistance to deal with adverse effects of climate change and meet their obligations to plan for measuring and possibly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In the final hours of COP 6, despite some compromises agreed between the United States and some EU countries, notably the United Kingdom, the EU countries as a whole, led by Denmark and Germany, rejected the compromise positions, and the talks in The Hague collapsed. Jan Pronk, the President of COP 6, suspended COP-6 without agreement, with the expectation that negotiations would later resume. It was later announced that the COP 6 meetings (termed “COP 6 bis”) would be resumed in Bonn, Germany, in the second half of July. The next regularly scheduled meeting of the parties to the UNFCCC – COP 7 – had been set for Marrakech, Morocco, in October–November 2001.

Bonn, Germany

COP 6 negotiations resumed July 17–27, 2001, in Bonn, Germany, with little progress having been made in resolving the differences that had produced an impasse in The Hague. However, this meeting took place after George W. Bush had become the President of the United States and had rejected the Kyoto Protocol in March 2001; as a result the United States delegation to this meeting declined to participate in the negotiations related to the Protocol and chose to take the role of observer at the meeting. As the other parties negotiated the key issues, agreement was reached on most of the major political issues, to the surprise of most observers, given the low expectations that preceded the meeting. The agreements included: