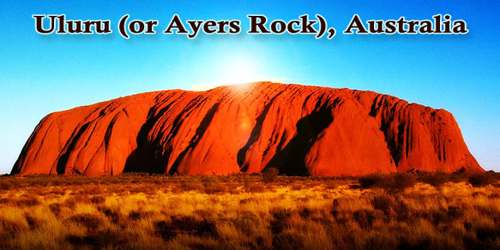

“Uluru” (/ˌuːləˈruː/, Pitjantjatjara: Uluṟu /ˈʊ.lʊ.ɻʊ/), also known as “Ayers Rock” (/ˌɛərz -/, like airs) and officially gazetted as Uluru / Ayers Rock, is a giant monolith, one of the tors (isolated masses of weathered rock) in southwestern Northern Territory, central Australia. It lies 335 km (208 mi) southwest of the nearest large town, Alice Springs. It has long been revered by a variety of Australian Aboriginal peoples of the region, who call it Uluru.

The rock (Uluru) was sighted in 1872 by explorer Ernest Giles and was first visited by a European the following year when surveyor William Gosse named it for Sir Henry Ayers, a former South Australian premier. It is the world’s largest monolith; “Mount Augustus (Burringurrah) in Western Australia is often identified as the world’s largest monolith, but, because it is composed of multiple rock types, it is technically not a monolith.” In 1993, a dual naming policy was adopted that allowed official names that consist of both the traditional Aboriginal name and the English name. On 15th December 1993, it was renamed “Ayers Rock / Uluru” and became the first official dual-named feature in the Northern Territory. The order of the dual names was officially reversed to “Uluru / Ayers Rock” on 6 November 2002 following a request from the Regional Tourism Association in Alice Springs.

Uluru is sacred to the Pitjantjatjara Anangu, the Aboriginal people of the area. The local Anangu, the Pitjantjatjara people, call the landmark Uluṟu (Pitjantjatjara [ʊlʊɻʊ]). The area around the formation is home to an abundance of springs, waterholes, rock caves, and ancient paintings. Uluru is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Uluru and Kata Tjuta, also known as the Olgas, are the two major features of the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park. According to Parks Australia:

“It is one of the few properties in the world to be dual-listed by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for outstanding natural values and outstanding cultural values. The park was first inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1987 when the international community recognized its spectacular geological formations, rare plants and animals and exceptional natural beauty. In 1994, the park became only the second in the world to be acclaimed for its cultural landscape as well. This listing honors the traditional belief systems as part of one of the oldest human societies on earth. We have a responsibility to protect the park’s World Heritage values. Traditional knowledge is combined with western science in caring for country.”

(Aerial View Of “Uluru”)

Uluru (or Ayers Rock) rises 1,142 feet (348 meters) above the surrounding desert plain and reaches a height 2,831 feet (863 meters) above sea level. The monolith is oval in shape, measuring 2.2 miles (3.6 km) long by 1.5 miles (2.4 km) wide, with a circumference of 5.8 miles (9.4 km). And yet most of Uluru is actually underground. Composed of arkosic sandstone, which contains a high proportion of feldspar, the rock changes color according to the position of the Sun; it is most visually striking at sunset when it is colored a fiery orange-red by the Sun’s rays. Its lower slopes have become fluted by the erosion of weaker rock layers, while the top is scored with gullies and basins that produce giant cataracts after infrequent rainstorms. Shallow caves at the base of the rock are sacred to several Aboriginal tribes and contain carvings and paintings. Kata Tjuta, also called Mount Olga or the Olgas, lies 25 km (16 mi) west of Uluru. Special viewing areas with road access and parking have been constructed to give tourists the best views of both sites at dawn and dusk.

Historically, 46 species of native mammals are known to have been living near Uluru; according to recent surveys, there are currently 21. Aṉangu acknowledges that a decrease in the number has implications for the condition and health of the landscape. Moves are supported for the reintroduction of locally extinct animals such as malleefowl, common brushtail possum, rufous hare-wallaby or mala, bilby, burrowing bettong, and the black-flanked rock-wallaby.

The region’s climate is hot and dry for much of the year, with considerable diurnal (day-night) temperature variation. Winters (May-July) are cool, and low temperatures at night frequently drop below freezing. Daytime highs often exceed 105 °F (40 °C) during the hottest month (December). Precipitation is highly variable and averages about 12 inches (300 mm) annually, with most falling from January to March; there are frequent periods of drought.

Uluru has a rich geological history but also a rich cultural history. The monolith is a holy place for the Anangu tribe, who have been in the area for around 10,000 years.

“Aboriginal culture dictates that Uluru was formed by ancestral beings during Dreamtime,” explains Uluru Australia. “The rock’s many caves and fissures are thought to be evidence of this, and some of the forms around Uluru are said to represent ancestral spirits. Rituals are still often held today in the caves around the base where ‘No Photography’ signs are posted out of respect.”

The Aṉangu also request that visitors do not photograph certain sections of “Uluru”, for reasons related to traditional Tjukurpa beliefs. These areas are the sites of gender-linked rituals and are forbidden ground for Aṉangu of the opposite sex to those participating in the rituals in question. The photographic restriction is intended to prevent Aṉangu from inadvertently violating this taboo by encountering photographs of the forbidden sites in the outside world.

A truly breathtaking place to behold, it attracts everyone from hikers to history buffs (who come mainly for the pre-historic petroglyphs that mark the caves nearby). However, Ayers Rock, as the site is also called, also figures as a focal point for the old traditions of the Australian Aborigines. They believe it’s one of the last remaining homes of the creator beings who forged the earth.

Information Sources: