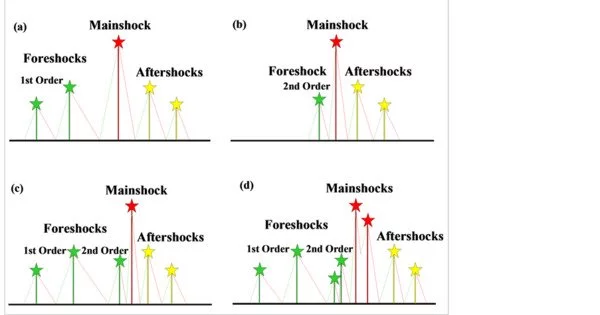

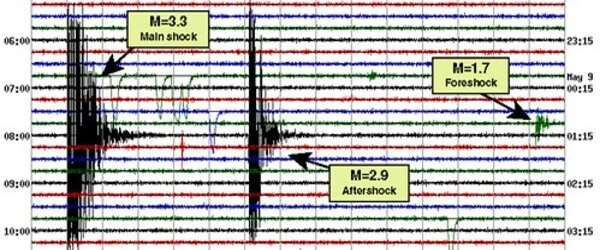

Foreshocks are smaller earthquakes that occur prior to a larger earthquake and can provide important information about the impending mainshock. Foreshocks are the most commonly identified signal of an impending mainshock earthquake, according to seismologists. But, do these foreshock sequences have distinguishing features that distinguish them from aftershock sequences, and can these features be used to forecast mainshocks?

Nadav Wetzler of the Geological Survey of Israel and colleagues identify some global trends in foreshock sequences for earthquakes of magnitude 7 or larger in a new paper published in Seismological Research Letters. These patterns identify the types of earthquakes and regions where foreshock sequences are more common.

Foreshocks “are one of the few—perhaps the only—observable phenomena precursory to upcoming dominant earthquakes,” said Wetzler. “However, foreshocks vary greatly in occurrence and their basic physical relationship to the mainshock remains enigmatic.”

As far as we know, this tendency for foreshocks has not previously been reported, despite similar circum-Pacific differences in aftershock productivity. The common tendency supports the general similarity of stress conditions influencing foreshock and aftershock productivity.

Nadav Wetzler

The researchers examined data from more than 400 mainshock earthquakes of magnitude 7 or greater in the National Earthquake Information Center’s global earthquake catalogue. To distinguish foreshocks from background seismic activity, they used three clustering algorithms. Wetzler and colleagues used these methods to determine that between 15% and 43% of large mainshocks have at least one foreshock, and 13% to 26% have at least one foreshock with a magnitude within two units of the mainshock’s magnitude.

They discovered that the percentage of foreshock occurrences is slightly higher for mainshocks that rupture along plate boundaries than for faults within a plate. In addition, foreshock sequences are more common in reverse faulting mainshocks (where the block above the faulting plane is compressed against the lower block) than in strike-slip or normal faults, according to the researchers.

Conditions that promote high aftershock activity appear to also promote high foreshock activity, according to Wetzler and colleagues. Although the exact conditions are unknown, the researchers speculate that the number of available faults or a critical stress threshold required to generate a cascade of seismic activity may control both types of sequences.

The researchers also noted that in their study, mainshocks in the western circum-Pacific region—in places like Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, west Aleutians, and the Kuril Islands—were prone to having slightly more foreshock activity than the eastern circum-Pacific in places like South America and Mexico.

According to Wetzler and colleagues, the difference may be due in part to differences in the age of the subducted plate. The faulted crust of older, thicker plates can host both foreshock and aftershock sequences.

“As far as we know, this tendency for foreshocks has not previously been reported, despite similar circum-Pacific differences in aftershock productivity,” Wetzler said. “The common tendency supports the general similarity of stress conditions influencing foreshock and aftershock productivity.”

While more research is needed to define this similarity, seismologists believe that foreshocks may be used more frequently as one of the forecasting tools for large earthquakes in areas with high aftershock activity.

The global composite b-value, a measure that characterises the relationship between earthquake magnitude and frequency of occurrence of earthquakes of a certain magnitude, appeared to distinguish foreshocks from aftershocks in the study. The researchers calculated a lower composite b-value for foreshocks than aftershocks for their global set of data.

However, when certain foreshock earthquakes in a sequence were excluded, the relationship became less consistent, and the researchers say it will be important to study this measure more closely for individual earthquakes.