Definition –

Turquoise is an opaque mineral (blue-to-green) that is a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is a birthstone for the month of December, and it is an 11th Anniversary gemstone. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of years owing to its unique hue. Like most other opaque gems, turquoise has been devalued by the introduction onto the market of treatments, imitations and synthetics. The gemstone has been known by many names. Pliny the Elder referred to the mineral as callais (from Ancient Greek κάλαϊς) and the Aztecs knew it as chalchihuitl.

Named from French “turques” or “turquoise” meaning “Turkish” the original material found on the south slopes of the Al-Mirsah-Kuh Mountains (Iran), but which found its way to Europe via Turkey. The name was known at least as early as the 17th century C.E. Turquoise and members of its group were redefined by Foord and Taggert in 1998, with turquoise reserved for an end-member composition. Foord and Taggert (1998) also noted that most of the gem material labeled “turquoise” is inhomogeneous and that planerite is the most common constituent in commercial “turquoise”.

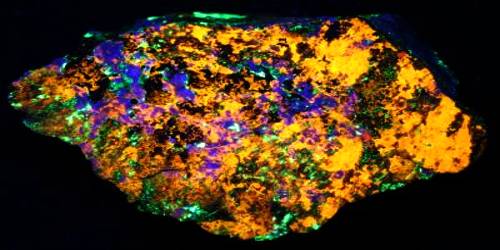

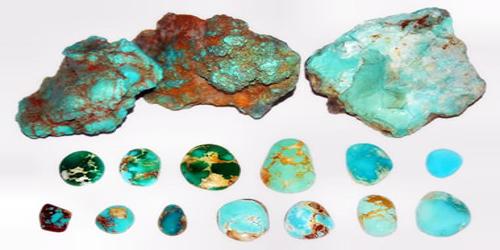

(Turquoise Rough and Cabochons)

Turquoise has been treasured as a gemstone for thousands of years. Isolated from one another, the ancient people of Africa, Asia, South America, and North America independently made turquoise one of their preferred materials for producing gemstones, inlay, and small sculptures.

Turquoise was obtained from the Sinai Peninsula before the 4th millennium BC in one of the world’s first important hard-rock mining operations. It was transported to Europe through Turkey, probably accounting for its name, which is French for “Turkish.” Highly prized turquoise has come from Neyshābūr, Iran. Numerous deposits in the southwestern United States have been worked for centuries by American Indians. Turquoise also occurs in northern Africa, Australia, Siberia, and Europe.

Very few minerals have a color that is so well known, so characteristic, and so impressive that the name of the mineral becomes so commonly used. Only three other minerals gold, silver, and copper have a color that is used more often in common language than turquoise.

Some Facts of Turquoise –

Mineral: Turquoise

Chemistry: CuAl6(PO4)4 (OH)8.5H2O

Color: Blue to green

Refractive Index: 1.610 to 1.650

Birefringence: Not detectable

Specific Gravity: 2.76 (+0.14, -0.36)

Mohs Hardness: 5 to 6

Occurrence and Properties of Turquoise –

Turquoise was among the first gems to be mined, and many historic sites have been depleted, though some are still worked to this day. These are all small-scale operations, often seasonal owing to the limited scope and remoteness of the deposits. Most are worked by hand with little or no mechanization. However, turquoise is often recovered as a byproduct of large-scale copper mining operations, especially in the United States.

Turquoise is rarely found in well-formed crystals. Instead, it is usually an aggregate of microcrystals. When the microcrystals are packed closely together, the turquoise has a lower porosity, greater durability, and polishes to a higher luster. This luster falls short of being “vitreous” or “glassy.” Instead many people describe it as “waxy” or “subvitreous.” Most of the world’s turquoise rough is currently produced in the southwestern United States, China, Chile, Egypt, Iran, and Mexico.

Iran has been an important source of turquoise for at least 2,000 years. It was initially named by Iranians “pērōzah” meaning “victory”, and later the Arabs called it “fayrūzah”, which is pronounced in Modern Persian as “fīrūzeh”. In Iranian architecture, the blue turquoise was used to cover the domes of palaces because its intense blue color was also a symbol of heaven on earth.

Since at least the First Dynasty (3000 BCE) in ancient Egypt, and possibly before then, turquoise was used by the Egyptians and was mined by them in the Sinai Peninsula. This region was known as the Country of Turquoise by the native Monitu. There are six mines in the peninsula, all on its southwest coast, covering an area of some 650 km2 (250 sq mi). The two most important of these mines, from a historic perspective, are Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi Maghareh, believed to be among the oldest of known mines. The former mine is situated about 4 kilometers from an ancient temple dedicated to the deity Hathor.

The Southwest United States is a significant source of turquoise; Arizona, California (San Bernardino, Imperial, Inyo counties), Colorado (Conejos, El Paso, Lake, Saguache Counties), New Mexico (Eddy, Grant, Otero, Santa Fe counties) and Nevada (Clark, Elko, Esmeralda County, Eureka, Lander, Mineral County, and Nye counties) are (or were) especially rich. The deposits of California and New Mexico were mined by pre-Columbian Native Americans using stone tools, some local and some from as far away as central Mexico. Cerrillos, New Mexico is thought to be the location of the oldest mines; prior to the 1920s, the state was the country’s largest producer; it is more or less exhausted today. Only one mine in California, located at Apache Canyon, operates at a commercial capacity today.

Turquoise can also replace the rock in contact with these waters. If the replacement is complete, a solid mass of turquoise will be formed. When the replacement is less complete, the host rock will appear as a “matrix” within the turquoise. The matrix can form a “spider web,” “patchy” design, or other patterns within the stone.

The color of turquoise ranges from blue through various shades of green to greenish and yellowish gray. A delicate sky blue, which provides an attractive contrast with precious metals, is most valued for gem purposes. Delicate veining, caused by impurities, is desired by some collectors as proof of a natural stone. Turquoise is opaque except in the thinnest splinters, takes a fair to good polish, and has a feeble, faintly waxy lustre. The stone’s color and lustre tend to deteriorate with exposure to sunlight, heat, or various weak acids.

The finest of turquoise reaches a maximum Mohs hardness of just under 6, or slightly more than window glass. Characteristically a cryptocrystalline mineral, turquoise almost never forms single crystals, and all of its properties are highly variable. X-ray diffraction testing shows its crystal system to be triclinic. With lower hardness comes lower specific gravity (2.60–2.90) and greater porosity; these properties are dependent on grain size. The lustre of turquoise is typically waxy to subvitreous, and its transparency is usually opaque, but may be semitranslucent in thin sections. Color is as variable as the mineral’s other properties, ranging from white to a powder blue to a sky blue, and from a blue-green to a yellowish-green. The blue is attributed to idiochromatic copper while the green may be the result of either iron impurities (replacing aluminium) or dehydration.

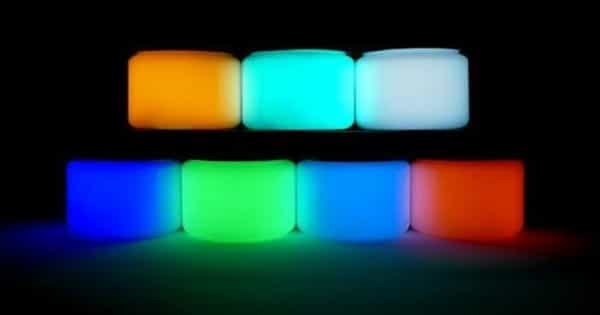

Several minerals are found where turquoise is expected, look similar to turquoise, are misidentified as turquoise, and often enter the gem and jewelry market labeled as turquoise. Turquoise has a refractive index of 1.61 to 1.65; this is a mean value seen as a single reading on a gemological refractometer, owing to the almost invariably polycrystalline nature of turquoise. A reading of 1.61-1.65 (birefringence 0.040, biaxial positive) has been taken from rare single crystals. An absorption spectrum may also be obtained with a hand-held spectroscope, revealing a line at 432 nm and a weak band at 460 nm (this is best seen with strong reflected light). Under longwave ultraviolet light, turquoise may occasionally fluoresce green, yellow or bright blue; it is inert under shortwave ultraviolet and X-rays.

Turquoise prehistoric artifacts (beads) are known since the fifth millennium BCE from sites in the Eastern Rhodopes in Bulgaria the source for the raw material is possibly related to the nearby Spahievo lead-zinc orefield. China has been a minor source of turquoise for 3,000 years or more. Other notable localities include: Afghanistan; Australia (Victoria and Queensland); north India; northern Chile (Chuquicamata); Cornwall; Saxony; Silesia; and Turkestan.

Healing Properties of Turquoise –

Turquoise is a purification stone. It dispels negative energy and can be worn to protect against outside influences or pollutants in the atmosphere. Turquoise balances and aligns all the chakras, stabilizing mood swings and instilling inner calm. It is excellent for depression and exhaustion, it also has the power to prevent panic attacks. Turquoise promotes self-realization and assists creative problem-solving. It is a symbol of friendship and stimulates romantic love.

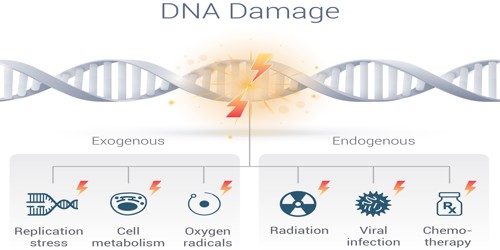

Turquoise aids in the absorption of nutrients enhances the immune system, stimulates the regeneration of tissue, and heals the whole body. It contains anti-inflammatory and detoxifying effects and alleviates cramps and pain. Turquoise purifies lungs, soothes and clears sore throats, and heals the eyes, including cataracts. It neutralizes over-acidity, benefits rheumatism, gout, stomach problems, and viral infections.

Uses and Benefits of Turquoise –

The earliest record of turquoise being used in jewelry or in ornaments is from Egypt. There, turquoise has been found in royal burials over 6000 years old. About 4000 years ago, miners in Persia produced a blue variety of turquoise with a “sky blue” or “robin’s-egg blue” color. This material was very popular and traded through Asia and into Europe. This is the source of the term “Persian Blue” color.

For most gem uses, turquoise is cut en cabochon, with a low-convex, polished upper surface. It may be carved or engraved, and irregular pieces are often set in mosaics with jasper, obsidian, and mother of pearl. Turquoise matrix, which is any natural aggregate of turquoise with limonite or other substances, is also valued.

Top-quality turquoise has inspired designers to create elegant jewelry. Its most often cut into cabochons, but it might also be cut into beads or flat pieces for inlays. Although much turquoise jewelry is sleek and modern, many US consumers are familiar with the traditional jewelry of Native American peoples such as the Pueblo, Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo. People interested in Native American arts and crafts frequently collect this stylized silver jewelry.

Being a phosphate mineral, turquoise is inherently fragile and sensitive to solvents; perfume and other cosmetics will attack the finish and may alter the color of turquoise gems, as will skin oils, as will most commercial jewelry cleaning fluids. After use, turquoise should be gently cleaned with a soft cloth to avoid a buildup of residue and should be stored in its own container to avoid scratching by harder gems. Turquoise can also be adversely affected if stored in an airtight container.

The best way to clean turquoise is with warm, sudsy water and a soft brush. It is important to dry it immediately with a cloth. Avoid any exposure to sharp blows, scratches, chemicals, sunlight or any high heat, dry air, and grease. Do not use commercial jewelry cleansers. Some porous specimens, especially in the US, may require an impregnation with resin or wax in order to resist fading and cracking.

Turquoise helps with blocks around giving and receiving forgiveness. People often have a tendency to push away people and memories that are painful or upsetting. Darkness and pain are universal human experiences, and only by integrating these aspects of existence can we become whole. This is never an easy process, but turquoise reminds us that we are not alone and indeed it is a journey everyone must make to heal. The end result turns these painful experiences into wisdom and compassion.

Information Sources: