A beer made from the hallucinogenic seeds of a South American tree may have aided an empire’s political stability. According to a new study published in the journal Antiquity, the Wari Empire – a pre-Columbian empire that existed in what is now Peru from around 600 to 1000 CE – may have been the first in the region to allow for mass consumption of psychedelic drugs, allowing the entire population to share in mind-altering experiences during large communal feasts. Several hallucinogenic plants were used by ancient Andean cultures, notably the mescaline-containing San Pedro cactus and the seeds of the Anadenanthera colubrina tree, often known as vilca. The latter contains an analog of the extraordinarily potent hallucinogenic chemical DMT, which has been consumed as snuff for at least 4,000 years by South American shamans.

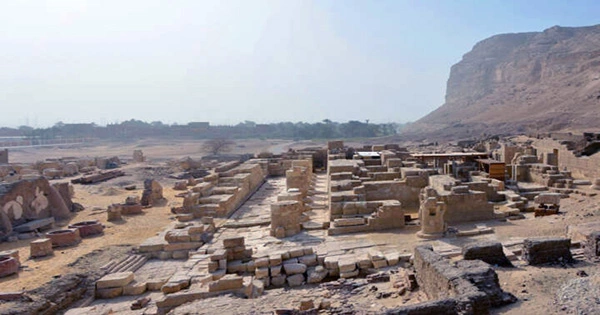

Because DMT is broken down in the stomach by monoamine oxidase (MAO), orally eaten vilca has no psychedelic effects unless it is combined with an MAO inhibitor, which is why it is traditionally insufflated. However, archaeologists discovered evidence of vilca seeds mingled with a type of beer known as chicha when excavating the Wari outpost of Quilcapampa. According to them, this could have amplified the hallucinogenic effects of the seeds. Chicha functioned as a “moderate MAO inhibitor,” according to the study. The addition of vilca to this concoction would have resulted in a psychedelic punch that might have been given out to participants at huge gatherings. The Wari elite appear to have broken with tradition by making the drug available to the entire population, a chemical that was previously exclusively available to high priests and kings.

The authors explain in their paper that while traditional vilca snorting “induced sharp, powerful psychotropic effects that were more conducive to an individualizing experience,” “the oral consumption of vilca in [chicha] changed the experience, most likely creating weaker but more enduring effects that could be enjoyed collectively.” By sharing this experience with the whole public, the Wari elite may have aimed to foster a strong link among all members of the community. At the same time, the rulers maintained their position of superiority by organizing great feasts and granting access to this miraculous brew, creating a sense of gratitude among the general population, who would otherwise never be able to enjoy such an event.

This increase in drug use can be considered as a watershed moment in ancient Andean geopolitics, leading to a fundamental transformation in how empires were organized. Early Andean dynasties preserved their hierarchical structure, according to the study authors, by limiting the use of sacred hallucinogenic herbs to elites, so preserving the power of these privileged individuals by allowing them exclusive access to spiritual realms. However, later civilizations like the Incan Empire are known to have relied on communal consumption of maize beer to sustain social cohesion.

The Wari’s embrace of vilca-infused chicha “represents a fulcrum of Andean political growth, when larger numbers of people might collectively experience the effects of a hallucinogen,” according to the study’s authors. “The ensuing psychoactive experience bolstered the Wari state’s strength and served as a bridge between exclusionary and corporate political practices,” they write. In other words, it appears that “Wari commanders were able to justify and retain their heightened position” by supplying their subordinates with drugs.