Background:

The creator has made the provision of only one food from the human body and that is breast milk. There were three determinants of good health, nutrition and child survival. Those are food security, care and disease control.

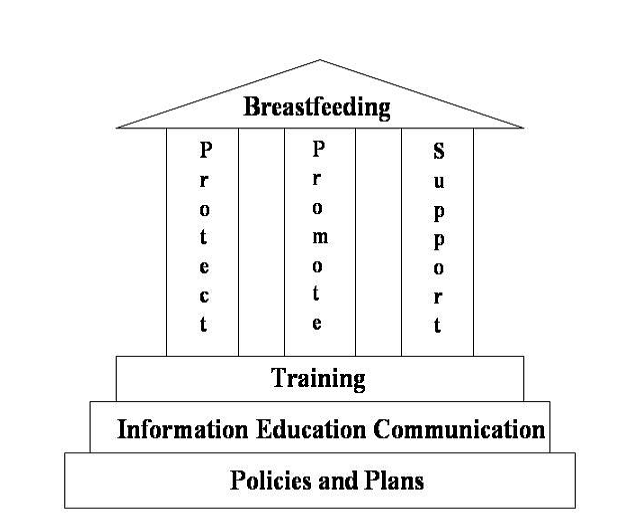

Breastfeeding is an optimal infant feeding behavior that offers considerable benefit to both mothers and infants. For this reason it has been endorsed by various health organizations . Besides being nutritionally superior to infant formula, human breast milk also contains immunological and antibodies that protect the infant from infections during the first few months of life when the infant’s immune system is not well develop. In an effort to improve the public’s health and to give children a healthy start in life, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other professional and international organizations (e.g., the World Health Organization and UNICEF) have issued statements; as well as instituted variety of programs, all in favor of promoting, protecting and supporting breastfeeding . The activities, resulting from the statements and programs of these professional and international organizations have subsequently reversed the downward trend in breastfeeding rates that existed worldwide prior to the last quarter of the last century .

The health and nutritional Status of mothers in Bangladesh is currently a major public-health concern. Almost half of Bangladesh mother of child bearing age suffer from chronic energy deficiency with a body mass index (BMI) less than 18.5 and more than 70% of pregnant women are anemic(17,18). Malnutrition, compounded by anemia, contributes to an increased low birth-weight rates (35- 50%) and a high maternal mortality rate (4/1, 000) in Bangladesh (19-21). Both knowledge and practice of appropriate infant and young children feeding practices (IYCF) was poor among mothers. Only 33% correctly knew that children should be exclusively breastfeed for six months and only 40% knew that complimentary feeding should be begin at six months of age. Breastfeeding was initiated within one hour for 48% of infants, exclusively breastfeed rate (EBR) less than six months of age was 58%, timely complimentary feeding at 6-9 months of age was 71% and the continued breastfeeding rate at 20-23 months was 89% (22). It is estimated that 4 million new born deaths occur every year globally. Recent research shows that, 22% new born deaths could be prevented if newborns initiated breastfeeding within one hour of birth, if all world newborns are began to breastfeed in one hour of birth, of the estimate 4 million new born death about one million lives will be saved.(23) Breastfeeding is universal in Bangladesh, and mothers breastfeed their babies, on average, for 28.2 months. (24)

Lactating mothers will lose their body-weight postpartum if they do not compensate with additional food intake. For women who exclusively breastfeed their children, the average energy costs for milk production are 595 kcal per day at 0-2 months post partum and 670 K.cal per day at 3-8 months. Energy needs are lower for women who partially breast feed, depending on the extent to which supplementary foods are given to the child. Studies in developing countries have consistently shown that energy in take during lactation is considerably lower than recommended . In Bangladesh, production of mother’s milk is limited by poor nutritional status and concentration of nutrients in milk declined with infants age . The effect of lactation on postpartum body-weight is controversial; some studies have not found any association , some reported postpartum -weight gain and many studies have shown a significant weight loss of lactating mothers after postpartum period.

Exclusive breastfeeding for six month means that the infant receives only breast milk, from his or her mother or a wet nurse, or expressed breast milk and no other foods or drinks with the exception of drops or syrups consisting of vitamins, minerals supplements, or medicines during this time. After six months, breastfeeding should continue for two years or more, with complementary foods. Maternal nutritional variably affects breast milk volume. Mild to moderate malnutrition affected minimally the volume and the quality, while serve malnutrition reduces milk output and fat, protein, vitamin and mineral contents to a greater extent.

Breast feeding is a unique process that provides ideal nutrition for children and contributes to their health growth and development, reduces incidence and severity of infections disease there by lowering infant morbidity and mortality . From the moment of birth up to the age of five months, breast milk is all the food drink a baby needs.

The effect of breast feeding on nutritional state, morbidity, and child survival was examined prospectively in a community in rural Bangladesh. Every month for six months health workers inquired about breast feeding and illness and measured arm circumference in an average of 4612 children aged 12-36 months. Data from children who died within one month of a visit were compared with those from children who survived. Roughly one third of the deaths in the age range 18-36 months were attributable to absence of breast feeding. Within this age range protection conferred by breast feeding was independent of age but was evident only in severely malnourished children. In communities with a high prevalence of malnutrition breast feeding may substantially enhance child survival up to 3 years of age.

1.2: Exclusive Breastfeeding:

Human milk is the ideal nourishment for infants’ survival, growth and development.exclusive breastfeeding means starting breastfeeding as early as possible within one hour of birth and babies receiving only breast milk for the first six months. It is the safe, sound, and sustainable way to feed an infant for the first six months of life. But breastfeeding is important for more than six months and should continue for 2 years or beyond along with appropriate and adequate complementary feeding starting after six months . Babies grow and develop best when they are fed in this way. Mothers can achieve both exclusive and continued breastfeeding when they know how valuable it is, when they know how to do it, and when they are given the necessary support. Experts now agree that breast milk can provide all that a baby normally needs for the first six months and no extra drinks or feeds are needed during this period . Exclusive breastfeeding means that the infant receives only breast milk, from his or her mother or a wet nurse, or expressed breast milk, and no other foods or drinks.

Exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life stimulates babies’ immune systems and protects them from diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections – two of the major causes of infant mortality in the developing world and improves their responses to vaccination. Particularly in unhygienic conditions, however, breastmilk substitutes carry a high risk of infection and can be fatal in infants. Yet only slightly more than one third of all infants in developing countries are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life.

Figure: Foundation of Breastfeeding

1.3: Breast feeding and supplementation:

UNICEF and WHO recommend that children be exclusively breastfed(no other complementary liquid or solid food or plain water)for the first six months of life and that children be given solid(semi solid) complementary food beginning with the seventh month of life. The standard indicator of exclusive breastfeeding is the percentage of children less than six months of age who are exclusively breastfeed. The standard indicator of timely complementary feeding is the percentage of children age 6-9 months who are breastfeeding and receiving complementary foods. Giving other milk to children is acceptable after the first six months, but breastfeeding is recommended to be continued through the second year of life(42).

1.4: Initiation and Age pattern of Breastfeeding:

UNICEF and WHO recommend that children be fed colostrums immediately after birth and continue to be exclusively breastfed even if the regular breast milk has not yet come down. Early breast feeding increases the changes of breast feeding success and generally lengthens the duration of breastfeeding. Early initiations of breastfeeding also encourage bonding between the mother and newborn and it helps to maintain the baby’s body temperature.

For optimal growth it is recommended that infants should be exclusively breasted for the first six months of life. Exclusive breastfeeding is the early months of life is correlated strongly with increased child survival and reduced risk of morbidity, particularly from diarrhoeal disease .

The Canadian Pediatric Society recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life for healthy, term infants. Breast milk is the optimal food for infants, and breastfeeding may continue for up to two years and beyond. This recommendation, proposed by the CPS Nutrition Committee and adopted by the Board of Directors in March 2005, extends the duration of exclusive breastfeeding from the former range of four to six months . It is also consistent with recently published recommendations from Health Canada and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. These changes follow the World Health Organization’s 2001 recommendation that exclusive breastfeeding continue for six months. The WHO defines exclusive breastfeeding as the practice of feeding only breast milk (including expressed breast milk) and allows the baby to receive vitamins, minerals or medicine. Water, breast milk substitutes, other liquids and solid foods are excluded.

The reasons behind the new recommendation include strong protective effects for infant gastrointestinal infection, prolonged lactational amenorrhea and increased post-partum weight loss in mothers. There were concerns that this recommendation could result in iron deficiency, other micronutrient deficiencies and growth faltering in susceptible infants. These concerns were directed particularly at populations where maternal nutrition was suspect, and infants had high rates of iron, zinc and vitamin A deficiency. However, an 8% global increase in exclusive breastfeeding to six months is estimated to have reduced infant mortality by 1,000,000, decreased fertility by 600,000, and saved countries billions of dollars in unneeded breast milk substitutes . While the data for benefit in industrialized countries is limited, it does exist . Nutrient-rich complementary foods, with particular attention to iron, should be introduced at six months. Breastfed babies should also receive a daily vitamin D supplement until their diet provides a reliable source or until they reach one year of age.

1.5: Benefits of breastfeeding:

Once thought to be “no longer worth the bother” , breastfeeding has been rediscovered by modern science as a means to save lives, reduce illness, and protect the environment. Policy makers are increasingly recognizing that breastfeeding promotion efforts can reduce healthcare costs and enhance maternal and infant well-being.

The current recommendation is that infants be exclusively breastfed for approximately the first six months of life and that breastfeeding be continued, complemented by appropriate introduction of other foods, well past the first year of life and as long as both mother and infant wish(. The National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention objectives call for an increase to at least 75% of the proportion of mothers who initiate breastfeeding and to increase to at least 50% the portion who continue to breastfeed until their infants are six months old.

With the extensive research now available on the benefits of breast milk and the risks of artificial milks, physicians need to be able to support their breastfeeding patients. Unfortunately most physicians currently in practice have had little to no education in breastfeeding physiology and clinical management. Well researched basic principles and guidelines exist, in addition to well educated lactation professionals and mother-to mother resources, to help the physician help his or her patients.

1.5.1: Importance of breastfeeding for infants:

Human milk is uniquely suited for human infants:

- Human milk is easy to digest and contains all the nutrients that babies need in the early months of life.

- Human milk contains special enzymes to optimally digest and absorb the nutrients in the milk before infants are capable of producing these enzymes themselves.

- Breast milk contains multiple growth and maturation factors.

- Factors in breast milk protect infants from a wide variety of illnesses.

- Breast milk contains antibodies specific to illnesses encountered by each mother and baby.

- Research suggests that fatty acids, unique to human milk, play a role in optimal infant brain and visual development.

- In several large studies, children who had been breastfed had a small advantage over those who had been artificially fed when given a variety of cognitive and neurological tests, including measures of IQ.

Breastfeeding saves lives:

- Lack of breastfeeding is a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

- Human milk seems to protect the premature infants from life-threatening gastrointestinal disease and other illnesses.

Breastfed infants are healthier:

- Infants who are exclusively breastfed for at least four months are half as likely as artificially fed infants to have ear infections in the first year of life.

- Breastfeeding reduces the incidence and lessens the severity of bacterial infections such as meningitis, lower respiratory infections, bacterium and urinary tract infections in infants.

- Breastfeeding is protective against infant botulism.

- Breastfeeding reduces the risk of “baby-bottle tooth decay” in infants.

- Breastfed infants are less likely to have diarrhea.

- Evidence suggests that exclusive breastfeeding for at least two months protects susceptible children from Type I insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM).

- Breastfeeding may reduce the risk of subsequent inflammatory bowel disease and childhood lymphoma.

- Breastfeeding confers some protection against allergy.

- New research suggests that older children and adults who were breastfed as infants, are likely to have less adult illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, hypertension and auto-immune diseases.

1.5.2: Importance of breastfeeding for mother:

Breast feeding helps mothers recover from childbirth:

- Breastfeeding helps the uterus to shrink to its pre-pregnancy state and reduces the amount of blood lost after delivery.

- Breastfeeding mothers return to their pre pregnant weight more rapidly than bottle-feeding mothers.

- Breastfeeding mothers usually resume their menstrual cycles 20 to 30 weeks later than bottle-feeding women.

Breastfeeding keeps women healthier throughout their lives:

- Breastfeeding can be an important factor in child spacing among women who do not use contraceptives.

- Breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

- Women who breastfeed their infants are less likely to develop multiple sclerosis.

- Breastfeeding may reduce the risk of osteoporosis.

- During lactation, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels decline while the beneficial HDL level remains high.(75,76) Carbohydrate metabolism is also improved.

- Breastfeeding promotes maternal confidence.

1.5.3: Importance of breastfeeding for society:

Breastfeeding is economical:

- The cost of artificial baby milk has increased 150% since the 1980’s.

- If no California infants were breastfed, the cost of artificial baby milk alone would exceed $400 million per year.

- Breastfeeding reduces healthcare costs for infants with less gastrointestinal, respiratory and other infant illnesses and less hospital admissions.

- Breastfeeding may reduce healthcare costs long-term via a healthier child, adolescent and adult population.

- Employers benefit from breastfeeding via healthier infants and children and less parent absenteeism from work.

Breastfeeding is environmentally sound:

- Unlike artificial baby milk, breastfeeding requires no fossil fuels for its manufacture or preparation.

- Breastfeeding reduces pollutants created as byproducts during the manufacture of plastics and artificial baby milk.

- Breastfeeding reduces the burden on our landfills.

- Breastfeeding represents the most efficient conversion of plant material into an ideal high-protein, high-energy food for infants.

- Breastfeeding performs a critical global ecological function by averting nearly as many births as all other modern contraceptive methods combined.

1.6: Mortality, Morbidity and breastfeeding:

Breastfeeding promotion is a key child survivalstrategy. Although there is an extensive scientific basis forits impact on post neonatal mortality, evidence is sparse forits impact on neonatal mortality.

The child survival revolution of the 1980s led to dramaticreductions in overall child mortality, it had little impacton neonatal mortality. In 2002, 4 million infants died duringthe first month of life, and neonatal deaths now account for36% of deaths among children <5 years of age. Tacklingneonatal mortality is essential if the millennium developmentgoal for child mortality is to be met. The promotion of breastfeeding is a key component of child survival strategies. Furthermore, the recent Lancet neonatal survival series included breastfeeding in its recommended package of interventions to reduce neonatal mortality. International policy places emphasis on exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life, with some groups promoting early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth. Although there is an extensive scientific basis for the impact of breastfeeding on post neonatal mortality, evidence is sparse for its impact on neonatal mortality and, to our knowledge, nonexistent for the contribution of the timing of initiation to any mortality impact. Maternal colostrum, produced during the first days after delivery, have been long thought to confer additional protection because of its immune and no immune properties. However, epidemiological data indicate that a high proportion of neonatal deaths are a result of obstetric complications, and these are unlikely to be affected by colostrum, transitional breast milk, or mature breast milk.

Breastfeeding was initiated within the first day of birth in 71% of infants and by the end of day 3 in all but 1.3%of them; 70% were exclusively breastfed during the neonatal period. The risk of neonatal death was fourfold higher in children given milk-based fluids or solids in addition to breast milk.There was a marked dose response of increasing risk of neonatal mortality with increasing delay in initiation of breastfeeding from 1 hour to day 7; overall late initiation (after day 1)was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in risk. The size of this effect was similar when the model was refitted excluding infants at high risk of death or when deaths during the first week were excluded.

Promotion of early initiation of breastfeeding has the potential to make a major contribution to the achievement of the child survival millennium development goal; 16% of neonatal deaths could be saved if all infants were breastfed from day1 and 22% if breastfeeding started within the first hour. Breastfeeding-promotionprograms should emphasize early initiation as well as exclusivebreastfeeding. (87)

1.7: Breastfeeding practices and its effect:

Breast milk, is an appropriate source of nutrition, provides the infants with immunological protection, and is generally free from contamination. Infant feeding practices have serious implications for infant survival and growth.(102,103) There is a general increase in .breastfeeding rates in countries across the world, the proportion of mothers breastfeeding in the US has been disappointingly low compared to other developed countries (15,14,106).

Some researchers and health professionals have found various degrees of violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes even among countries who have officially adopted the Code (107-109). In Hong Kong, for example, researchers have found formula companies to promote infant and follow-on formula in hospitals and also provide free supplies of their products to hospitals to be given to pregnant women and mothers (109) with similar practices in Africa (108).

A study was reports regional differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration but confirms the disparities in breastfeeding by socio-demographic characteristics in the US found in other studies. In this study by Ryan et al. western states recorded the highest rate of breastfeeding initiation in the hospital (81.3%) which exceeds the Healthy People 2010 goal of 75%. The rates of breastfeeding initiation in New England, Northern and Southern Regions were 73%, 67.6% and 65.1%, respectively. The trend was similar for breastfeeding rates at 6 months ranging from 28.8% in Southern to 42.5% in Western United States, with these rates being lower than the Healthy People 2010 goal of 50%. The incidence and duration of breastfeeding was not influenced by socio-demographic characteristics across regions although the authors observed influence of these maternal characteristics on initiation and duration of breastfeeding within regions of residence (16).

Across the globe, maternal age has been found to be associated with initiation, exclusiveness and duration of breastfeeding (110, 111). For example, in their study of 8,362 mothers in the United States, Ryan and co-workers (16) found older mothers to be more likely compared to their younger counterparts to initiate breastfeeding and to continue breastfeeding at 6 months. Similarly, recent results from the 2002 US National Immunization Survey consisting of 3,444 mothers showed that at 6 months 43% of mothers 30 years or older were still breastfeeding compared to only 17% of their younger counterparts (< 20 years) while 20% and 11%, respectively, were still breastfeeding at 12 months postpartum (112). There is also evidence that strongly suggests a positive association between maternal age and the duration of exclusive breastfeeding in the US (112,113).

In Vietnam researchers have reported a higher percentage of exclusive breastfeeding among women with more than high school education (68%) compared to only 32% among those with high school or less education. Similarly, in the US, some researcher have reported higher percentages of breastfeeding initiation and duration among mothers with more than high school education compared to their counterparts with high school or less education. (16,104,105,110,112,114), while maternal level of education continues to be shown to have positive association with exclusive breastfeeding across countries, Nath and Goswami in India found an inverse association. In this study involving 5000 couples from Guwahati, the capital city of Assam, India, Nath and Goswami reported that the median length of exclusive breastfeeding was longer for mothers with less than lower primary education (5.45 months) than those with some high school (3.86 months) and high school graduates (3.60 months).(115). In another study among rural Moslem women in Israel, researchers found mothers with < 8 years of education were about 2.5 times (OR 2.45) and 1.5 times (OR 1.64) more likely to be breastfeeding at 3 and 6 months, respectively, compared to their counterparts with > 9 years of education (116).

Researchers have found associations between breastfeeding and marital status (47, 5 9-61, 64). For instance, results of a secondary data analysis involving 556 women who delivered at two hospitals in Perth, Western Australia, indicate that married women are more likely to be breastfeeding at hospital discharge (OR 1.41; 95% CI: 1.00-1.98) than single mothers (105).

In a prospective study of 247 mothers from the UK who delivered singleton births, Ward and co-workers reported that married mothers were more likely to initiate breastfeeding at hospital discharge (80.2 % vs. 66.7%) and exclusively breastfeeding at 6 and 14 weeks postpartum (91.1% vs. 74.1% and 93.8% vs. 75.5%, respectively) than single mothers. (117) Similarly, among 425 Australian mothers, Binns reported that mothers who were married were more likely to breastfeed at hospital discharge than single/never married mothers (OR 1.74; 95% CI: 0.76-3.99).(118). Data from the 2002 US National Survey also suggest improved breastfeeding outcomes among married women than among their single counterparts (112).

Breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity and duration have been reported to be influenced by different psychosocial factors. Partner and maternal grandmother support have been consistently identified as being positively associated with the initiation, exclusivity and duration of breastfeeding (105,117,118,114). Support from health care workers such as doctors, nurses/lactation consultants and breastfeeding counselors have all been found to impact breastfeeding (119,116, 120-125). Researchers have also found higher breastfeeding incidence and duration among mothers who attend ante-natal breastfeeding classes (105,118). In a study of 1059 women delivering at two rural and two urban hospitals in Australia, Scott et al. (105) concluded that, support from partners (OR: 10.92; 95% CI: 6.50-18.32)), maternal grandmother (OR” 5.91; 95% CI: 3.37-10.39), and attendance to ante-natal classes (OR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.01-1.92) were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of breastfeeding at hospital discharge. Other researchers have demonstrated that breastfeeding initiation, exclusiveness and duration increase if mothers have access to breastfeeding support either from a lactation consultant or a peer counselor irrespective of ethnicity or country of birth, education and marital status (120-127). In general, mothers are more likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding if they have access to psychosocial support of one form or the other.

In UK, a study on “Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding (Cochrane Review)” Karmer and Kakuma conclude that they found no objective evidence of a ‘Weanling’s dillema’. Infants who are exclusively breastfeed for six months experience less morbidity from gastrointestinal infection than those who are mixed breastfeed as of 3 or 4 months, and no deficits have been demonstrated in growth among infants from either developing and developed countries who are exclusively breastfeed for 6 months or longer. Moreover, the mothers of such infants have more prolonged lactational amenorrhea. Although infants should still be managed individually so that insufficient growth or other adverse outcomes are not ignored and appropriate interventions are provided, the available evidence demonstrates no apparent risk in recommending, as a general policy, EBF for the first 6 months of life in both developing and developed country settings. Large randomized trials are recommended in both type of setting to rule out small effect on growth and to confirm the reported health benefits of EBF for 6 months or beyond. (128)

In Brazil in a study the interactions between individual and contextual variables showed that the presence of at least four pro-breast-feeding measures in the municipality attenuated the risk of early termination of EBF associated with low maternal schooling and low birth weight, and transformed child follow-up in the public network into a protective factor against the early termination of breast-feeding. (129)

UNICEF and WHO recommend that breastfeeding continue for two years and beyond. Researchers in Kenya carried out a study to determine to what extent this recommendation affected child growth. 264 children in Western Kenya were measured and weighed for 6 months (range 9-18 months). The children were separated into three categories at follow-up: short, medium and long duration. Only 5.3% of the children were not breastfeeding at the beginning of the study. By the end of the study, 65.5% were still breastfeeding. Households with short duration of breastfeeding were wealthier than those with longer duration of breastfeeding. Results showed that the unadjusted weight and length gains during follow-up were significantly higher in the long-duration than in the short-duration breastfeeding. The longest-duration breastfeeding group gained 3.4 cm and 370 g more than those in the shortest-duration group. (130)

Researchers in Denmark studied 1’656 infants at the age of 8 months to determine whether breastfeeding affected mental development below the age of 1 year. Three developmental milestones were measured: crawling, pincer grip, and polysyllable babbling. Duration of breastfeeding was classified according to the number of months of exclusive breastfeeding. The results showed that 38.8% of the 7-month olds could babble in polysyllables. 93.7% of the mothers had exclusively breastfed their children for at least 1 month, with 65.7 % continuing until 4 months. The proportion of children who had mastered the milestones increased consistently with increased duration of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF). For example, 73.4% of babies who were exclusively breastfed for 6 months or more were polysyllable babblers versus 48.5 % of babies who had been exclusively breastfed for only 1 month. There was little or no confounding from various factors like family social status, mother’s education, gestational age or mother’s employment. (131)

In Nepal a study showed the rates of initiation within one hour and within 24 hours was 72.7% and 84.4% respectively. Exclusive breastfeeding was practiced by 82.3% of the mothers. Breasmilk/colostrum was given as first feed to 332 (86.2%) babies, but 17.2% of them were either given expressed breast milk or were put to breast of other lactating mothers. Pre-lacteal feeds were given to 14% of the babies. The common pre-lacteal feeds given were formula feeds (6.2%), sugar water (5.9%), and cow’s milk (2.8%).logistic regression analysis, friends’ feeding practices, type of delivery, and baby’s first feed were the factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding practice of the mothers. (132)

An another study revealed that the exclusive breastfeeding rate for four months was 79.2 percent of the sample mothers, It was found that encouragement from parents and relatives were significantly associated to the breastfeeding patterns of the mothers. There was also a significant association between family income of the mothers and their breastfeeding practice. Husbands were the main persons in supporting their wives in helping with household chores (95.5%) while health care providers were the main resources providing information about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding and the disadvantages of bottle-feeding (61.1%). Since returning to work (44.5%) and getting pregnant again (22.3%) were the main reasons for mothers to quit exclusive breastfeeding practice. (133)

In India a study show the age range of women under study was 20-34 years. Women were selected regardless of parity. A large proportion of women were housewives belonging to middle class family and coming from urban area. Out of a total of 70 women, 33 practiced exclusively breastfeeding their youngest child at fixed time whereas, 37 on demand of the child.

A community-based cross sectional study was done in urban slums of Gwalior, India. The data were collected by interviewing the caregivers of 279 infants aged between 6 and 11 months from November 2005 to July 2006. Only 11 (3.8%) mothers knew that EBF should be done till six months and 22 (7.8%) actually practiced EBF. A total of 178 (63.8%) and 212 (76.0%) newborns were given pre- and post-lacteal feeds with 26.2% discarding colostrums. Only 22 (7.8%) practiced EBF. The early breastfeeding (BF) initiation, Ante Natal Clinic (ANC) visits, mothers’ education and immunization visits were significantly associated with higher probability of EBF. There were a number of myths and misconceptions about BF in this urban slum population. The correct information about BF was more common amongst the women who had frequent contacts with health facilities due to any reason or during ANC or immunization visit.

In Bangladesh data from a national survey entitled Surveillance on Breastfeeding and Weaning Situation and Child and Maternal Health in Bangladesh were used to investigate the exclusive breastfeeding practice and to examine the factors having influence on child nutrition. It was that 16% of women still exclusively breastfed their children for less than 6 months. Of the children 38.1% were stunted and 38% were under weight for their age. Overall, 46% of children were suffering from diseases. Bivariate analysis showed that maternal education and family income were important correlates of exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusively breastfed children were nutritionally better off. Logistic regression analysis showed that the children of illiterate women were nutritionally more vulnerable than children of women who had secondary and higher education. The children of older age women were less likely to be stunted than children of younger age women. (136)

On the other hand a study was show that the mean age of mothers was 25.15 years .The large majority of them had formal schooling, with 46.46 having education up to secondary level. Of them 90.5% were housewives, 60.3% lived in nuclear family, and 27.6% had a monthly family income of Tk 6,000-10,000. 63.8% used breast milk substitutes to feed their children and of them, 90.6% gave infant formula, and 9.4% gave other substitutes. Healthcare providers, such as doctors and nurses, mostly influenced the decision about the feeding of breast milk substitutes. As many as 87.8 % of respondents fed breast milk substitutes according to advice of others. Of them, doctors and nurses influenced, respectively, 76.5% and 4.4% of the mothers. Insufficiency of breast milk was the main reason (63.5%) for introducing breast milk substitutes. The rate of exclusive breast-feeding was only 17.2%, irrespective of pre-lacteals. Regarding the source of getting breast milk substitutes, it was reported that 40.5% of the mothers bought them from medical stores inside the healthcare facilities. No significant differences were observed in feeding breast milk substitutes among mothers who had received antenatal care and who did not. But antenatal care was associated positively with colostrums feeding. It was also evident that pre-lacteal feeding was associated with increased use of breast milk substitutes by mothers. (137)

According to 10th round survey of breastfeeding surveillance of BBF (September 2004) in Bangladesh, more than one third (34.9%) of the mother initiated breastfeeding more than one hour after birth. However, more than 32% children were breastfeed within 30 minutes of birth and about 29% received breast milk between 30 minutes and one hour. Among the mothers who did not breastfeed their child, more than 44% reported that there was no milk in the breast. The majority (78.6%) of the mothers reported that they gave pre-lacteal feed. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months was 17.8%. Prevalence of EBF without pre-lacteal at 5 and 6 months were 9.7% and 3.6%. More than 96% of the mothers feed colostrums to their babies. 69% of the mothers who did not feed colostrums to their children had no breast milk. (138)

The 2004 BDHS data, almost all Bangladeshi babies are breastfeed for the first year of life. Even among 20-23 months old children, 94% are receiving breast milk. However, the data indicate that supplementation of breast milk with other liquids and foods begin early aim Bangladesh. Among infants less then 2 months, slightly more then half (55%) are being exclusively breastfed, while the remaining are being given water and other liquids in addition to breast milk.(139) According to (CBI) 2003, another study showed in Bangladesh Breastfeeding is initiated at 97% but full EBF at 6 months is reported to be 45%.(140)

The NNP intended to provide mothers with regular counseling on the use of colostrums and exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months, and the continuation of breastfeeding until the age of 2 years. Mothers, as well as fathers, mother-in-law, and other caregivers were encouraged to introduce locally breastfeeding practices. This focused on breast-feeding at the individual level was supported by a emphasis in the national behavior changes communication activities. (141)

A study was conducted on “Duration of Breast-feeding in Bangladesh” in 2004 by Giashuddin et al. In this study the median duration of EBF was 3.67 months whereas mean and median duration of continued breastfeeding was 31.3 and 30 months respectively, Life table analysis showed that 69.9% women gave supplementary food to their babies before completing 6 months of age. Women who had lived in rural areas were less likely to terminate breast-feeding then those living in urban areas. Women who had completed at least secondary education were less likely to stop breast-feeding then less or uneducated mothers. Children born to high economic status families had higher risk of stopping breast-feeding compared to those of low economic status families. According to the study result, women with higher education, high economic level, lower birth interval and delivery assisted by the health personnel had lower duration of breastfeeding. (142)

In another study, the proportion of infants who were breastfed exclusively was only 6% at enrollment, increasing to 53% at one month and then gradually declining to 5% at 6 months of age. Predominant breastfeeding declined from 66% at enrollment to 4% at 12 months of age. Very few infants were not breastfed, whereas the proportion of partially breastfed infants increased with age. Breastfeeding practices did not differ between low and normal birth weight infant at any age. The overall infant’s mortality rate was 114 deaths per 1000 lives births. Compared with EBF in the first few months of life, partial or no breastfeeding was associated with a 2.23-fold higher risk of infant deaths resulting from all causes and 2.40- and 3.94-fold higher risk of deaths attributable to ARI and diarrhea, respectively. The important role of appropriate breastfeeding practices in the survival of infants is clear from this analysis. (143)

In 2003, Giashuddin et al assessed exclusive breastfeeding practice and examined the factors effect on nutritional status of children from 0 to 24 months of age. It was found that 16% of women still exclusively breastfed their children for less then 6 months. Bivariate analysis showed that maternal education and family income were important correlates of exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusively breastfed children were nutritionally better off. Despite efforts of different government agencies and NGOs, EBF rate was still low in Bangladesh. Traditional cultural barriers still exist. In order to remove the harmful cultural believes and to spread the messages of the benefit of EBF for survival and nutritional status of the children more behavior change communication should be maid to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. (144)

In 2000, WHO Collaborative Study on the Role of Breastfeeding on the prevention of Infant Mortality found that breastfeeding is protective against diarrhea and ARI. (143)

In 2001, the WHO expert consultation on the optimal duration of EBF affirmed the importance of breastfeeding and its protection against diarrhea and recommended EBF for 6 months. (144)

In Bangladesh fertility survey (BFS) in 1975/6 found that 98% of infants were breast-feeding and the mean duration was more than 27 months. A large Matlab study in 1985/6, found a mean length of breast feeding of 28.8 months in a project area were maternal and child health services had been introduced (146,147).

In addition, A study of the Nutritional Knowledge, Food Habits and Infant Feeding Practices among two income groups in Dhaka, shows the opinion on the duration of exclusive breast-feeding, most higher income mother responded correctly (5 months) while about half the lower income mothers advocated five mothers and half seven months. 11.2% said 12 months was the correct duration. About one third of the higher income groups exclusively breast-feed for 1 to 3 months and a little more than half did so for 4 to 6 months. In the case of lower income group, 19.8% exclusively breast feed for 1 to 3 months, 38.8% for 4-6 months, 37.1% for 7-9 months and the rest for above 9 months. The reasons given by the woman for not exclusively breast-feeding for the full 4-6 months was work out side the home, shortage of milk, mother’s bad health, etc. The number of higher income group mothers exclusively breast feed for the correct duration was significantly higher than the number of lower income mothers whom did not. (148)

1.8: Rationale:

To improve exclusive breastfeeding rate in Bangladesh we able to know the specific reasons of low level knowledge of mother. We can also know the difference between nutritional status of exclusively breastfeed and non-exclusively breastfeed infants. Mother and their infants would be benefited by this study.

1.9: Hypothesis:

We hypothesized that Exclusively Breastfeed infants were healthier to compare with non Exclusively Breastfeed infants and Exclusively Breastfeed infant’s socio-economic level is higher than Non-Exclusively Breastfeed infants.

Objectives

1.10: General Objectives:

1. To assess the determinants of exclusive feeding in infants (0-6 months).

1.11: Specific Objectives:

- To compare nutritional status of exclusively breastfed infants with those who are not exclusively breastfeed.

- To compare the socioeconomic indicators of mothers who are exclusively breastfeeding with those who are not.

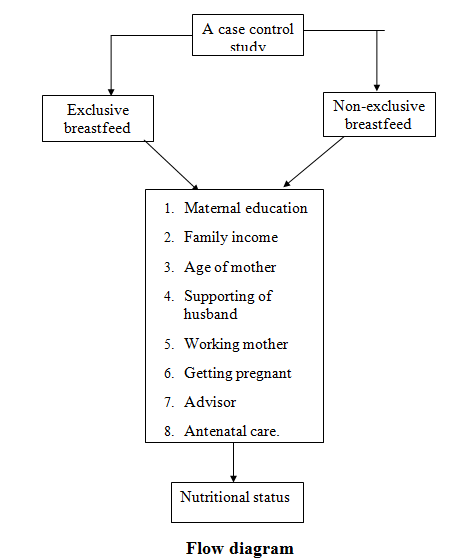

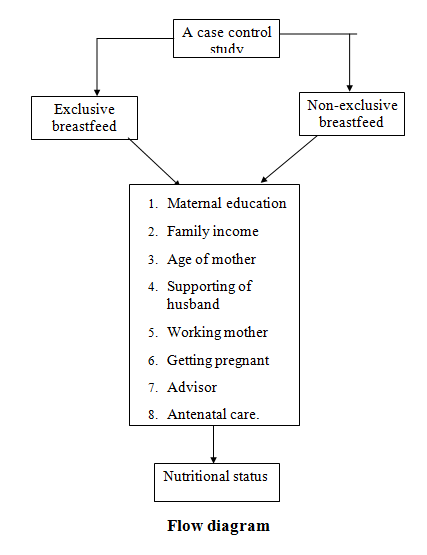

2.1: Study design:

Hospital based Case-control study was conducted in ICMH, DSH, ICDDR,B for the available breastfeed mothers who came for treatment of their infants in those hospital.

2.1: Study design:

Hospital based Case-control study was conducted in ICMH, DSH, ICDDR,B for the available breastfeed mothers who came for treatment of their infants in those hospital.

2.2: Study population:

The study population was breastfed mother who had 0-6 months infant.

2.3: Study area:

1: Institute of Child and Mother Health, Dhaka.(ICMH)

2: Dhaka Sishu Hospital.(DSH)

3: ICDDR,B

2.4: Subject:

Ι. Inclusion criteria:

- Exclusively Breastfeed women who live in urban area.

- Non Exclusively Breastfeed women who live in urban area.

ΙΙ. Exclusion criteria:

1. Woman (age < 15 years)

2. Elderly woman (age > 50 years)

3. Twin babies.

4. Unwillingness.

2.5: Sample size calculation (149):

A case control study(Sample size of each group)

π1= Proportion of control exposed

OR= Odds ratio

π0 =Proportion of case exposed

Calculated from

π= Proportion

U = One sided Percentage point of normal distribution corresponding to 100%-the power.

π1, π0 = Proportions.

V = Percentage of the normal distribution corresponding to 100% – the power.

2.6: Total Sample size:

So the total sample size was 79×2=158. Considering 10% dropout, the total number of the sample size was (87+87) =174, approximately it was 180 (90 in each group).

2.7: Questionnaire development:

A questionnaire, for the study was used, that consists of-

- Family information

- Socioeconomic factors

- Reproductive history of infant’s mother.

- Current breastfeeding practices

- Breastfeeding and illness of infant

- Anthropometry of infant

- Anthropometry of infant’s mother

2.8: Data collection instruments:

Pencil, eraser, questioners, height scale, weight machine.

2.9: Data Collection:

- Quantitative data collection:

- Anthropometry (weight, length) – Weight was taken using weighting scale, length was measured using length board.

- We were also collect information on their feeding behavior, knowledge and perception on food security.

- Qualitative data collection:

The data was collected through individual interview. Information of socio-economic condition, feeding practice, history of disease, awareness about breastfeeding and complementary feeding of the mothers infant was collected through direct questionnaire.

2.10: Data Entry & Analysis:-

After completing the study, coded data were entered in to SPSS software. Consistency, validity and accuracy of data entry were checked and cleaned using the validation program. Analysis had done using standard statistical software (SPSS). Statistical test was selected for checking the distribution of the variables. T-test was done for comparison of two data points among the same subjects. X2-test was used to test the difference in proportion between groups. Cross tabulation was used for description of data.

2.11: Out come variables:

- Maternal education

- Family income

- Age of mother

- Supporting of husband

- Working mother

- Getting pregnant

- Advisor

- Insufficiency of breast milk

- Friend’s feeding practice

- Type of delivery

- family type and area

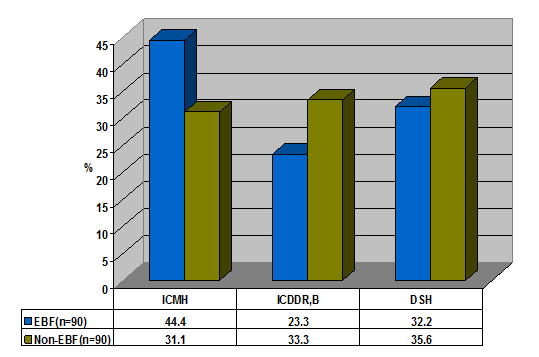

Figure-1

Distribution of the all exclusive and non-exclusive breastfed infants by Hospitals

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 3.853, P value= 0.146

Figure 1 shows percentage distribution of exclusive and non exclusive infants in ICMH, ICDDR,B and DSH hospitals. Here 44.4% of mother breastfeed their infants exclusively and 31.1% non-exclusively in ICMH. About 23.3% of infants were exclusively breastfeed and 33.3% of infants were non-exclusively breastfeed in ICDDR,B. In DSH, 32.2% of infants were breastfeed exclusively and 35.6% of infants non-exclusively. In comparison infants who visit to ICMH their EBF rate is higher than other two hospitals (ICDDR,B & DSH).

Family information

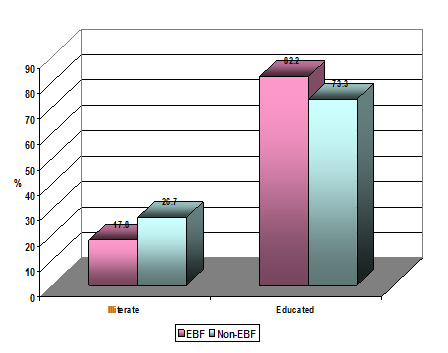

Table-1: Comparison of exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeed infants between their mother’s education levels:

| Education level of mother | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n=90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||||

Educated

Chi-Square (χ2) =2.05, P value= 0.151

Educational attainment of the mothers is represented in table 1. For convenience, the academic qualification is divided in two categories namely illiterate and educated. Educational attainment of the mothers shows: 17.8% of mother illiterate and 82.2% was educated feed their infants exclusively. On the other side 26.7% illiterate and 73.3% were educated mothers feed their infants non-exclusively. There was no significant difference between EBF and Non-EFB mother’s education level.

Figure-2

Comparison of exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeed infants between educated and illiterate mothers

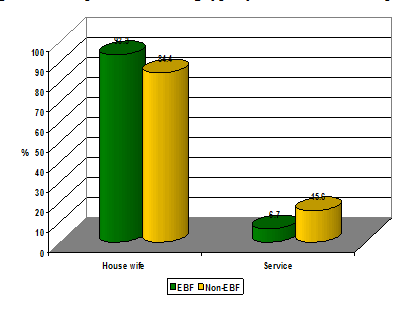

Table-2: Comparison of all infants by their mother’s occupation:

| Occupation of mother | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| House wife | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =3.600, P value= 0.058

Table 2 shows the distribution of the infant’s mother by their occupation and main differences observed that 93.3% of house wives feed their infants exclusively and 84.4% of them feed their infants non-exclusively. Only 6.7% of service holder mother feed their infants exclusively and 15.6% non-exclusively. There was a significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF mother’s occupation.

Figure-3: Comparison of feeding type by their mother’s occupation

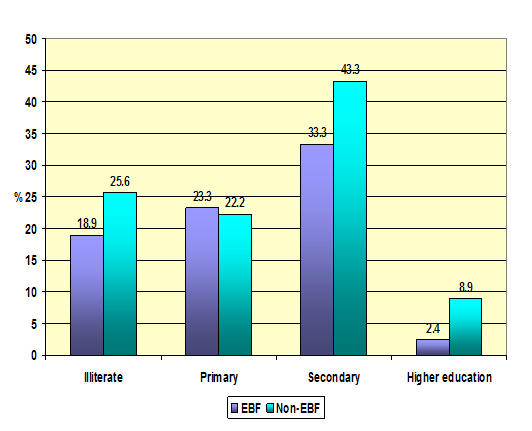

Table-3: Percentage distribution of all exclusive and non-exclusive breastfed infants by their father’s educational qualification:

| Level of education | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Illiterate | |||||

Chi-Square (χ2) =8.63, P value= 0.035

Table 3 shows the distribution of the infant’s father’s educational level according to Exclusive Breast feed and Non-exclusive Breastfeed babies group. For convenience, the academic qualification is divided in four categories namely illiterate, primary, secondary and higher educated. The result shows 18.9% of exclusively breastfeed and 25.6% non-exclusively breastfeed infants father were illiterate. 22.8% (23.3% of EBF and 22.2% of Non-EBF) completed primary level and 38.3% accomplished secondary level (33.3% of EBF and 43.3% of Non-EBF). Among them only 16.7% (2.4% of EBF and 8.9% of Non-EBF) were completed higher education. There was a significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF infants father’s education levels.

Figure-4

Distribution of all exclusive and non-exclusive breastfed infants by their father’s educational qualification

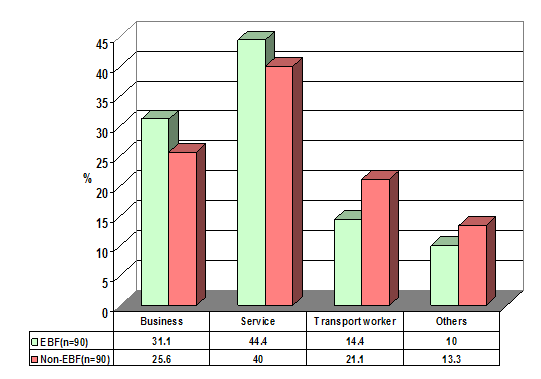

Figure-5

Comparison of feeding type by their father’s occupation

**Chi-Square (χ2) =2.25, P value= 0.521

Figure 5 depicts the distribution of the infants by their father’s occupation and main differences observed that 44.4% of service holder feed their infants exclusively and 40.0% non-exclusively. Only 31.1% businessman feed their infants exclusively and 25.6% non- exclusively. There was no significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF infant father’s occupation.

House hold and socio-economic profile

Table-4: Percentage distributions of the respondents according to their household characteristic:

Materials of family | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | P value | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Electricity | |||||

Table 4 shows that 91.1% exclusive breastfed infants family had electricity,66.7% had table,78.9% had watch,53.3% had TV,73.3% had telephone/mobile, 63.3% had bed and almira. Among Non-exclusive breastfeed infants family had 96.7% electricity, 74.4% had table, 78.9% had watch, 65.6% had TV, 62.2% had telephone/mobile, 77.7% had almira and 55.6% had bed.

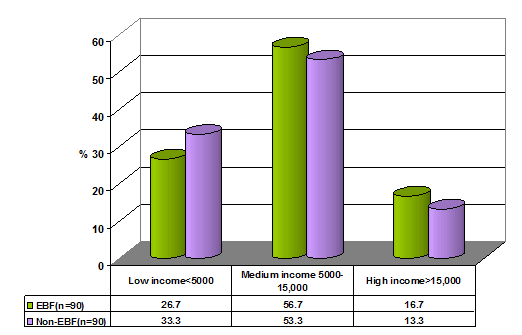

Figure-6

Percentage distribution of all exclusive and non- exclusive breastfed infants according to their monthly family income

Chi-Square (χ2) =1.795, P value=0.773

Figure 6 Shows information about the total monthly family income of the mothers. Total monthly family income of a family directly reflects their socio-economic status. For convenience, total monthly family income was divided in to three categories as Low income TK. <5000, Medium income TK 5000-15000 and High income TK. >15000. The result shows that 56.7% of exclusively breastfed and 53.3% non-exclusively breastfeed infants family income was Tk. 5000 to 15,000. Other hand 16.7% exclusively breastfeed and 13.3% non-exclusively breastfeed infants family income was more then TK.15000. Although, no significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF infants by their monthly family income.

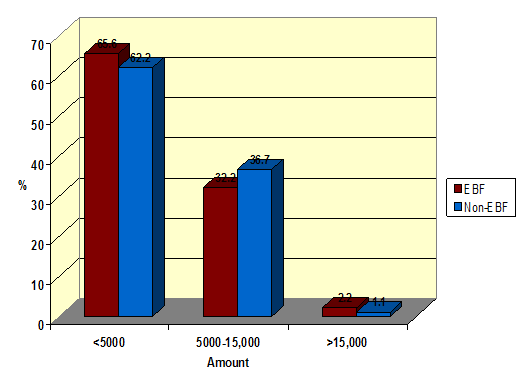

Table-5: Percentage distributions of the all exclusive and non- exclusive breastfed infants according to their monthly food expenditure:

| Amount of monthly food expenditure | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| <5000 | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =1.654, P value=0.6

Table 5 shows the distribution of the household total monthly food expenditure. The result shows that 65.6% of exclusively breastfed and 62.2% non-exclusively breastfeed infants family expend less than tk.5000 for food. As well as 32.2% of exclusively breastfed and 36.7% non-exclusively breastfeed infant’s family expend Tk.5000 to 15000 for food. Only 1.7% (2.2% of exclusively breastfed and 1.1% non-exclusively breastfeed) infants family expend more than Tk.15000 for food. There was no significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF infants by their monthly expenditure for food.

Figure-7

Distributions of the all exclusive and non-exclusive breastfed infants according to their monthly food expenditure

Reproductive history of mother

Table-6: Percentage distributions of the all infants by their mother’s age:

| Age of mother | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| <20 years | |||||

Chi-Square (χ2) =2.277, P value= 0.131

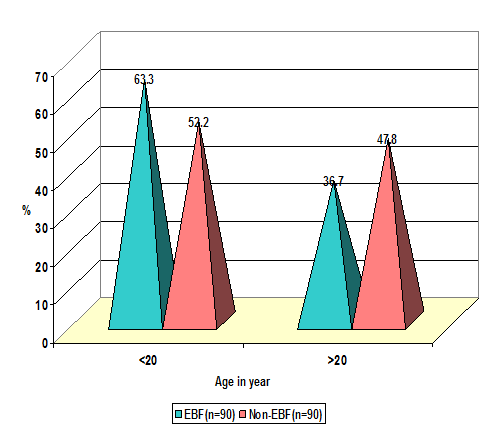

Table 6 provides the age of infants mother. They are divided in to two age groups as <20 years and >20 years. The result shows that majorities (57.8%) of the infant mother’s age was less than 20 years, where 63.3% of them feed their infants exclusively and 52.2% Non-exclusively. On the other hand 36.7% exclusively breastfeed and 47.8 % non-exclusively breastfeed infant’s mother age was grater than 20 years. There was no significant difference between two groups by their mother’s age.

Figure-8

Percentage distribution of feeding type by their mother’s age

Table-7: Distribution of the infants by their mother’s age of first marriage:

| Mother’s age | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| <20 | |||||

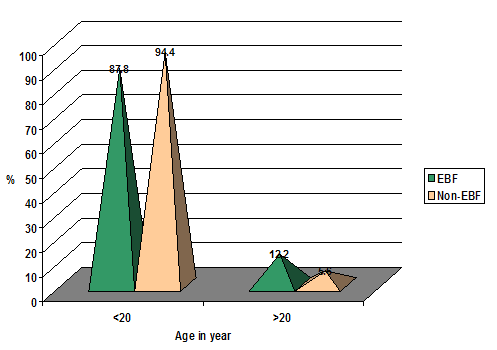

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 2.470, P value =0.116

Table 7 informs about the age of first marriage of the mothers. For study purpose, mothers are divided in to two age groups as <20 years and >20 years. The result shows that 87.8% of EBF and 94.4% Non-EBF mother’s first marriage age was less than 20 years. However 12.2% of EBF and 5.6% Non-EBF mother’s first marriage age was greater than 20 years. Here we can figure out that those mother’s first marriage age was less then 20 years among them the proportion of Non-EBF rate was higher than those mother’s whose age was greater than 20 years. Although, no significant difference between two groups. But there was little difference between EBF and Non-EBF infant’s mother by first marriage age.

Figure-9: Distribution of the infants by their mother’s age of first marriage

Table-8: Group-wise distributions of infants according to their mother’s age at first child birth:

| Mother’s age | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| >20 | |||||

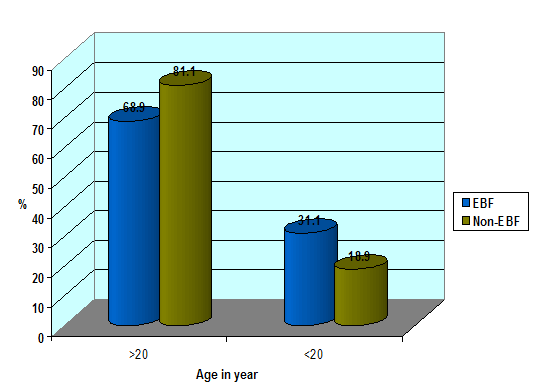

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 3.585, P value =0.058

Table 8 shows mother’s age at first child birth. To get relevant information on early pregnancy or late pregnancy mothers are divided in to two age groups as <20 years and >20 years. The result shows that 68.9% of EBF and 81.1% Non-EBF mother’s first child birth age was less than 20 years. However 31.1% of EBF and 18.9% Non-EBF mother’s first child birth age was greater than 20 years. Here we can figure out that mothers who got their first baby under 20 years among them the proportion of Non-EBF rate was higher than that mother’s who got their first baby after 20 years. There was significant difference between two groups by their mother’s first child birth.

Figure-10

Distribution of the infants by their mother’s age of first child birth

Table-9: Group-wise distribution of infants according to their mother’s number of receiving ANC check-up during pregnancy:

| Number of receiving medical checkup | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| No visit | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =4.171, P value =0.124

Table 9 gives information about the total number of ANC check-up during pregnancy. The result shows that 18.9% mothers did not receive any ANC check-up during pregnancy. However most of them (43.3% of exclusively breastfed and 56.7% non-exclusively breastfed infants mother) received more than four times ANC check-up during pregnancy. Other side 37.8% of exclusively breastfed and 24.8% non-exclusively breastfed infant’s mother received less than four times ANC check-up during pregnancy. There was no significant difference between two groups.

Table-10: Distribution of infants according to their mother’s place of delivery:

| Place of delivery | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Home delivery | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =0.452, P value =0.798

Table 10 shows the place of delivery. The result shows that most of the mother delivery was in home, where 85.6% exclusively and 82.2% non-exclusively breastfed. Only 6.7% mother’s delivery was in hospital (5.6% EBF and 7.8% Non-EBF). As well as 9.4% mother’s delivery was in private clinic (8.9% EBF and 10% Non-EBF). There was no significant difference between two groups by their place of delivery.

Table-11 Comparison of the all infants according to type of delivery:

| Type of delivery | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Normal | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =1.772 P value =0.183

This table informs about the delivery case. The result shows that 67.8% of exclusively breastfed mothers had normal delivery and 32.2% had caesarian. However 76.7% of non-exclusively breastfed mothers had normal delivery and 23.3% had caesarian respectively.

Current Breastfeeding practice

Table-12: Distribution of the infants according to their age:

| Age in month | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| One month | |||||

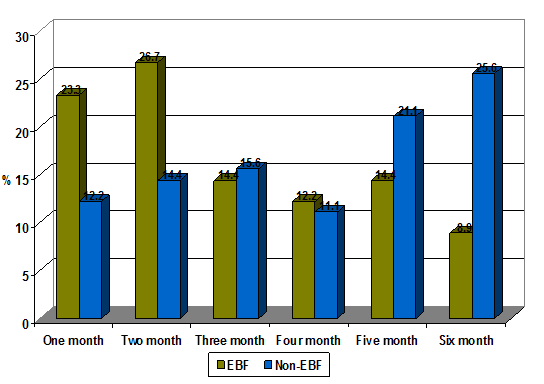

**Chi-Square (χ2) =14.86, P value =0.011

Table 12 shows the prevalence of breastfeeding according to the infants age. The result shows that 23.3% of infants age one month, 26.7% infants age two month and 8.9% infants age six month were exclusively breastfed. On the other contrary 25.6% of infants age six month, 21.1% infants age five months and 11.1% of infants age four months, 15.6% infants age three months were non-exclusively breastfeed. This analysis shows that three and five month is the risk month of infant’s lifetime. Because in those month exclusive breastfeeding rate was began to decrease. There was highly significant difference between two groups.

Figure-11

Distribution of the infants according to their age

Table-13: Comparison of infants between two groups according to sex:

| Sex of children | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) (%) | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Male | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =0.206, P value = 0.650

Table 13 gives information about the percentage of the infants according to their sex. The result provide that 60% male and 40% female infants were exclusively breastfed and 56.7% male and 43.3% female infants were non exclusively breastfed.

Table-14: Distribution of infants according to receiving colostrums just after birth:

| Type | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Received | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =1.429 P value =0.232

Table 14 shows the prevalence of receiving colostrums just after birth. Here 95.6% exclusively breastfed infants received colostrums just after birth and 4.4% did not. Other hand 91.1% non-exclusively breastfed infants received colostrums just after birth and 8.9% did not. There was no significant difference between two groups.

Figure-12

Timely initiation of the breastfeeding between exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeed infants just after birth

**Chi-Square (χ2) =1.937, P value =0.747

Figure 13 informs the time of initiation of breastfeeding after birth. Here 24.4% exclusively and 30% non-exclusively breastfed infants were breastfeed immediately. As well as 38.9% exclusively and 30% non-exclusively breastfed infants were breastfeed within 2 hours. Respectively 20% exclusively and 21.1% non-exclusively breastfed infants were breastfeed after 24 hours. Only 15.6% exclusively and 16.7% non-exclusively breastfed infants were breastfeed within 24 hours.

Table-15: Distribution of infants according to practice of Pre-lacteal feeding after birth:

| Given Pre-lacteal feeding | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Yes | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =0.370, P value =0.543

Table 15 informs the practice of pre-lacteal feeding. 37.8% Exclusive Breastfed and 42.2% Non-Exclusive Breastfed infants were given pre-lacteal feed. On the other side 62.2% of Exclusive Breastfed and 57.8% of Non-Exclusive Breastfed infants were not given any pre-lacteal feed.

Table-16: Distribution of infants according to Comparison of proportion of different type of pre-lacteal feeds between Exclusive Breastfed and Non- Exclusive Breastfed group:

| Pre-lacteal food items | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

| n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Nothing given | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =5.331, P value =0.502

Table 16 shows the types of pre lacteal food items. The result shows the majority (60%) of mothers did not give their infants any pre lacteal food after birth. However 13.3% exclusively breastfed and 17.8% non-exclusively breastfeed infants mother gave honey. The next common pre-lacteal food item was sugar water. 16.7% exclusively breastfed and 10% non-exclusively breastfeed infants mother gave sugar water. Respectively 4.4% exclusively breastfed and 5.6% non-exclusively breastfeed infants mother gave tinned milk. Remaining 1.1% exclusively and 3.3% non-exclusively breastfeed infant’s mother gave cow or goat milk.

Table-17: Distribution of infants according to reasons of pre-lacteal feeding:

| Reasons | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Nothing given | |||||

**Chi-Square (χ2) =2.172, P value =0.704

Table 17 reveals the reasons of pre-lacteal feeding. The mother who did not breastfeed their infants just after birth, among them 14.4% both Exclusive Breastfed and Non- Exclusive Breastfed mother reported that there is no milk on the breast, and 6.6% both Exclusive Breastfed and Non- Exclusive Breastfed reported that the mother was sick.

Table-18: Distribution of infants according to continuing breastfeeding:

| Type | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Yes | 89 | 98.9 | 67 | 74.4 | 86.7 13.3 100 |

| No | 1 | 1.1 | 23 | 25.6 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | 90 | 100 | |

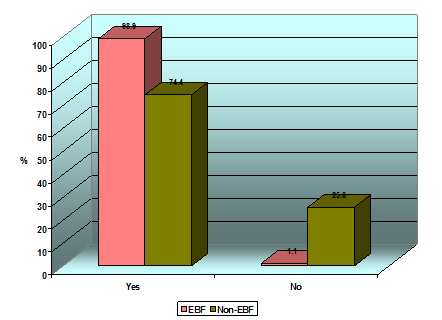

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 23.269, P value =0.001

Table 18 informs that 98.9% exclusive breastfed and74.4% non exclusive breastfed infants was continuing breastfeeding. 1.1% exclusive breastfed and 25.6% non-exclusive breastfed infants was not continuing breastfeeding. There was highly significant difference between two groups.

Figure-13: Distribution of infants according to continuing breastfeeding

Table-19: Cleaning habit of breast before or after feeding:

| Type | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Always washing | |||||

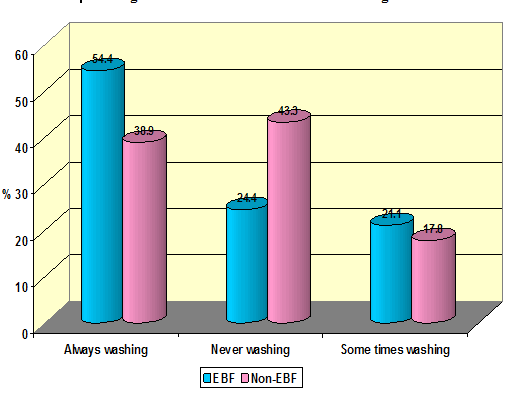

**Chi-Square (χ2) =7.328, P value =0.026

Table 19 informs the washing habit of infant’s mother. The table shoes that 54.4% exclusive breastfed and 38.9% non exclusive breastfed mothers always wash their breast before feeding. Other side 24.4% exclusive breastfed and 43.3% non exclusive breastfed mothers never wash their breast before feeding and 21.1% exclusive breastfed and 17.8% non-exclusive breastfed mothers sometimes wash their breast before feeding. There was a significant difference between two groups.

Figure-14

Cleaning habit of breast before or after feeding

Table-20: Enrolled in any breastfeeding counseling programme:

Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | |||

n | (%) | N | (%) | 6.1 93.9 100 | |

| Yes | 6 | 6.7 | 5 | 5.6 | |

| No | 84 | 93.3 | 85 | 94.4 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | 90 | 100 | |

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 0.97, P value =0.756

Table 20 informs that 6.7% exclusive breastfed and 5.6% non exclusive breastfed mothers enrolled breastfeeding counselor program. 93.3% exclusive breastfed and 94.4% non-exclusive breastfed mothers did not enrolled any breastfeeding counselor program.

Table-21: Receiving advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy:

Type | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Received advice | 61 | 67.8 | 45 | 50.0 | 58.9 41.1 100 |

| Did not receive advice | 29 | 32.2 | 45 | 50.0 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | 90 | 100 | |

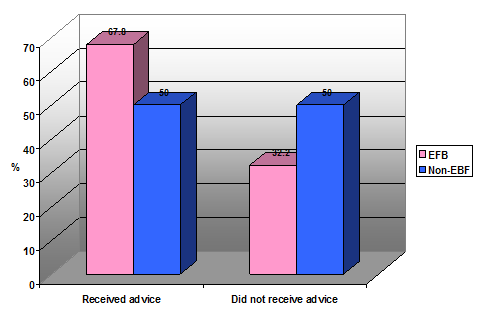

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 5.875, P value =0.011

Table 21 shows 67.8% exclusive breastfed and 50% non exclusive breastfed mothers provide advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy. 32.2% exclusive breastfed and 50% non-exclusive breastfed mothers does not provide any advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy.

Figure-15: Receiving advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy

Table-22: Adviser of the mother about breastfeeding during pregnancy:

Person | Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Doctor | 18 | 20.0 | 15 | 16.7 | 18.3 3.9 37.2 40.6 100 |

| Trained health person | 4 | 4.4 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Relative | 39 | 43.3 | 28 | 31.1 | |

| Nobody advice | 29 | 32.2 | 44 | 48.9 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | 90 | 100 | |

**Chi-Square (χ2) =5.304, P value = 0.151

Table 22 reveals the person who provides advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy of the infant’s mother. The result shows that 40.6% infant’s mother does not provide any advice from others. 43.3% exclusive breastfeed and 31.1% non exclusively breastfeed mother’s provide advice on breastfeeding by relative and 4.4% exclusive breastfeed and 3.3% non exclusively breastfeed mother’s provide advice on breastfeeding by trained health person. Beside that 20% exclusive breastfeed mother’s and 16.7% non-exclusively breastfeed mothers provide advice on breastfeeding by doctor.

Figure-16

Infant’s father appreciation about breastfeeding

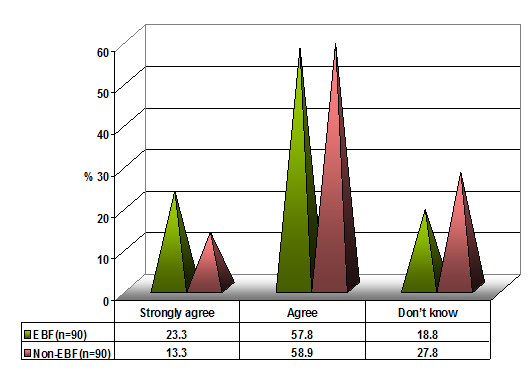

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 3.988, P value = 0.136

Figure 16 informs the husband appreciation about breastfeeding of infant’s mother. The table shoes that 57.8% exclusive breastfed and 58.9% non exclusive breastfed infant’s father agree about breastfeeding. Other side 18.8% exclusive breastfed infant’s father don’t know about breastfeeding and 13.3% non exclusive breastfed infants father strongly agree about breastfeeding.

Morbidity status of the infants

Table-23: Distribution of infants according to their illness over the past two week:

Problems | Exclusive breastfed(n =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(n =90) | P value | ||

n | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Have fever | |||||

Table 23 shows the morbidity status about the infants in our study between two groups. Here we can figure out that fever and flue was the common health problems in EBF and Non-EBF infants. So 64.4% of EBF and 65.6% Non-EBF infants were suffering from fever, 47.8% EBF and 44.4% Non-EBF were suffering in flue. We can also figure out that Non-EBF infants were suffering in different health problems more than EBF infants. EBF infant’s immune system is stronger than Non-EBF infants.

Anthropometry

Table-24: Comparison of the Mother’s anthropometry between two groups:

| Variables | X±SD | P value | |

Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | ||

| Mother’s ht(cm) | 150.6±6.5 | 149.9±5.9 | 0.47 0.29 0.53 |

| Mother’s wt(kg) | 48.6±7.9 | 47.4±7.8 | |

| Mother’s BMI | 21.4 ±3.1 | 21.1±3.4 | |

Table 24 shows that the Exclusive Breastfeed mother’s mean (± SD) height was 150.6±6.5 and mean(±SD) weight was 48.6±7.9. However Non-Exclusive Breastfeed mother’s mean(±SD) height was 149.9±5.9 and mean(± SD) weight was 47.4±7.8.Again, Exclusive Breastfeed mother’s mean (± SD)BMI was 21.4±3.1 Non-Exclusive Breastfeed mother’s mean (± SD)BMI was 21.1±3.4. Between EBF and Non-EBF mother’s there was no significant difference in mean height and BMI. However exclusive breastfeed mother’s weight was better than non-exclusive breastfeed mothers.

Table-25: Comparison of infants between two groups:

| Variables | X±SD | P value | |

Exclusive breastfed(N =90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | ||

| Infant’s ht(cm) | 55.2±6.8 | 55.9±6.4 | 0.42 0.69 |

| Infant’s wt(kg) | 4.9±1.5 | 4.9±1.6 | |

Table 25 shows that the Exclusive Breastfeed infants mean (± SD) height was 55.2±6.8 and mean (±SD) weight was 4.9±1.5. However Non-Exclusive Breastfeed infants mean (±SD) height was 55.9±6.4 and mean (± SD) weight was 4.9±1.6. There was no significant difference between two groups.

Nutritional status of infants

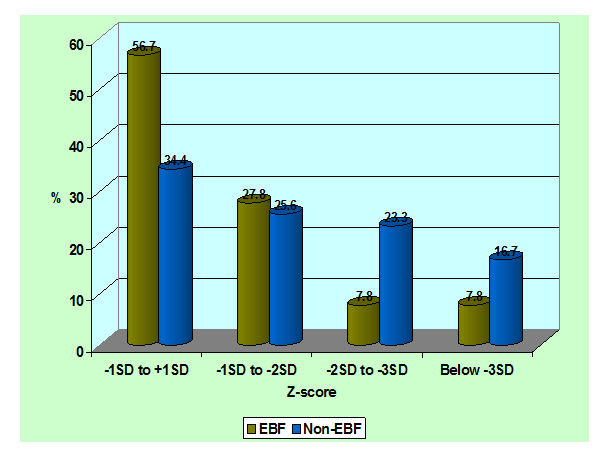

Table-26: Distribution of all infants according to their nutritional status:

Z-Score | Exclusive breastfeed(N=90) | Non-exclusive breastfed(N =90) | (N=180) % | ||

n | (%) | n | (%) | 45.6 26.7 15.6 12.2 100 | |

| -1SD to +1SD | 51 | 56.7 | 31 | 34.4 | |

| -1SD to -2SD | 25 | 27.8 | 23 | 25.6 | |

| -2SD to -3SD | 7 | 7.8 | 21 | 23.3 | |

| Below -3SD | 7 | 7.8 | 15 | 16.7 | |

| Total | 90 | 100 | 90 | 100 | |

**Chi-Square (χ2) = 14.870, P value =0.002

Table 26 informs the nutritional status of infants. The table shows that 56.7% of EBF and 34.4% Non-EBF infants were healthy. However 27.8% of EBF and 25.6% Non-EBF infants were mild malnourished, 7.8% EBF and 23.3% Non-EBF infants were moderate malnourished and 7.8% EBF and 16.7% Non-EBF infants were sever malnourished. We can clearly mention that exclusively breastfeed infants were healthier than non-exclusively breastfeed infants. There was highly significant difference between EBF and Non-EBF infants by their nutritional status.

Figure-17

Distribution of infants according to their nutritional status

4.1: Discussion:

Bringing a new baby into the world is one of the greatest and most profound experiences in life and it is the beginning stage of a lifelong relationship of loving and caring with this new creature. Feeding newborn baby is one of main starting time of relationship, which contributions to his normal growth and well being. Nature has provided with the most advanced, easiest and economic way of feeding new baby and it is called “BREASTFEEDING”. When a baby breastfeed, you providing him with the best possible infant food. But breastfeeding provides more than the best nutrition. It is more than the most convenient and economic method.

The importance and advantage of breast-feeding can barely be over stressed. It seems to have limitless values. Human milk is regarded as the ideal food for the optimum nutrition of human infants during the early months of life. The nutritional, immunological and physiological advantages of breast milk are well documented. It is the mainstay of protein nutrition for the first six months of life and is usually all that is needed for this period. (145) Infant period is the most vulnerable and critical time for human being so at the time of six months the proper feeding is needed for each infant’s growth and development. Breastfeeding has been rediscovered by modern science as a means to save lives, reduce illness, and protect the environment. (44, 45, 46)

The study was carried out among the 180 mother-child pair of three renowned hospitals in Bangladesh namely Institute of Child and Mother Health (44.4%EBF and 31.1%Non-EBF), International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (23.3%EBF and 33.3% Non-EBF) and DhakaShishuHospital (32.2%EBF and 35.6% Non-EBF). In comparison infants who visit to ICMH their EBF rate is higher than other two hospitals (ICDDR,B & DSH). Because ICMH hospital has Breastfeeding counseling opportunity while other two hospitals did not have this opportunity.

In our study majorities of the infants mother age was under 20 years. 63.3% of them feed their infants exclusively and 52.2% non-exclusively. On the other hand 42.3% of them age were grater than 20 years. As well as study shows that 17.8% of mother illiterate and 82.2% of them was educated feed their infants exclusively. On the other side 26.7% illiterate and 73.3% was educated feed their infants non-exclusively (P = 0.151). Here we can say that those mother’s who were literate among all of them EBR comparatively higher than illiterate mothers. So it is clear that there is a strong relation between education and Breastfeeding, and literate mother were more aware about Breastfeeding rather than illiterate mother.

In addition this study highlighted that 56.7% of EBF infants family income level was Tk. 5000 to 15,000 and only 16.7% income was more than Tk. 15,000. Beside that 53.3% of Non-EBF infants families monthly income level was tk.5000 to 15,000 and 13.3% income was more than Tk.15,000( P =0.773). We can figure out that the infants born in high and low economic status families had higher risk of stopping breast-feeding compared to those of middle class families. Because middle class family has sound knowledge about nutrition.

According to our study result, it shows the difference between two groups by their mother’s occupation and main differences observed that 93.3% of house wives feed their infants exclusively and 84.4% non-exclusively. Only 6.7% of service holder mother feed their infants exclusively and 15.6% non-exclusively (P= 0.058). Here those mothers were house wives their EBF rate was higher than service holder mothers. The reason is that house wives can gave more time to their baby as they stay home always. As well as when baby got hungry they can breastfeed while service holder mother was unable to feed their baby. Our analysis showed that mother’s education, occupation and family income were important correlates of exclusive breastfeeding.

In Bangladesh data from a national survey, showed that maternal education and family income were important correlates of exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusively breastfed children were nutritionally better off. Logistic regression analysis showed that the children of illiterate women were nutritionally more vulnerable than children of women who had secondary and higher education (136). In 2004 Giashuddin et al. found that women who had completed at least secondary education were less likely to stop breast-feeding then less or uneducated mothers. Children born to high economic status families had higher risk of stopping breastfeeding compared to those of low economic status families. According to the study result, women with higher education, high economic level and delivery assisted by the health personnel had lower duration of breastfeeding (142). In 2003 another study found that maternal education and family income were important correlates of exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusively breastfed children were nutritionally better off. (144)

Father’s educational level according to EBF and Non-EBF groups shows a significant variations about status of breast feeding (P = 0.035). Here 18.9% of them were illiterate, 23.3% completed primary level and 33.3% accomplished secondary level. Among them 24.4% were completed higher education, they feed their infants exclusively. On the other hand 25.6% of them were illiterate, 22.2% completed primary level, and 43.3% accomplished secondary level. Among them only 8.9% were completed higher education who feed their infants non-exclusively. It is clear that those fathers who were educated among them EBF rate comparatively lower than non educated father’s family. Here we find that infants father whose education level is high they influence their wife to feed their infants breastmilk substitutes.

The breast-feeding tradition in Bangladesh is without a doubt among the strongest in the world. In this study 98.9% of EBF and 74.4% Non-EBF infants were continuing breastfeeding. 1.1% of EBF and 25.6% Non-EBF infants was stopped breastfeeding (P=0.001). The reason of stopping breastfeeding was sickness of mother, not having enough breastmilk, lake of education and proper nutrition knowledge.

In Bangladesh fertility survey (BFS) in 1975/6 found that 98% of infants were breast-feeding and the mean duration was more than 27 months. A large Matlab study in 1985/6, found a mean length of breast feeding of 28.8 months in a project area were maternal and child health services had been introduced.(146,147)

In addition, A study of the Nutritional Knowledge, Food Habits and Infant Feeding Practices among two income groups in Dhaka, shows the opinion on the duration of exclusive breast-feeding, most higher income mother responded correctly (5 months) while about half the lower income mothers advocated five mothers and half seven months. The number of higher income group mothers exclusively breast feed for the correct duration was significantly higher than the number of lower income mothers whom did not. The reasons of not exclusively breast-feeding for the full 4-6 months was work out side the home, shortage of milk, mother’s bad health, etc.(149)

Our study shows that 87.8% of EBF and 94.4% Non-EBF mother’s first marriage age was less than 20 years. However 12.2% of EBF and 5.6% Non-EBF mother’s first marriage age was greater than 20 years (P =0.116).As well as 68.9% of EBF and 81.1% Non-EBF mother’s first child birth age was less than 20 years. However 31.1% of EBF and 18.9% Non-EBF mother’s first child birth age was greater than 20 years (P =0.058). Here that mother’s first marriage age was less then 20 years among them the proportion of Non-EBF rate was higher than that mother’s whose age was greater than 20 years. As well as mother who got their first baby under 20 years among them the proportion of Non-EBF rate was higher than that mother’s who got their first baby after 20 years. The reason is lack of nutrition knowledge and practice and unconscious about Breastfeeding. According to our study three and five month was the risk month of infant’s lifetime. (P =0.011) Because in those months exclusive breastfeeding rate was began to decrease.