Several studies have been undertaken in numerous domains, including psychology, neuroscience, and animal behavior, to investigate how social rank impacts stress reactions. These studies frequently seek to understand how a person’s place in a social hierarchy influences their physiological and psychological responses to stimuli.

According to the researchers, this findings could shed light on stress-related mental diseases, but more research is needed. Can a person’s social position influence their degree of stress? Tulane University researchers investigated this question and discovered that social rank, particularly in females, does alter stress response.

Tulane psychology professor Jonathan Fadok, PhD, and postdoctoral researcher Lydia Smith-Osborne investigated two types of psychosocial stress, social isolation and social instability, and how they manifested themselves dependent on social status in a study published in Current Biology.

We analyzed how these different forms of stress impact behavior and the stress hormone corticosterone (an analogue of the human hormone, cortisol) in individuals based on their social rank. We also looked throughout the brain to identify brain areas that are activated in response to psychosocial stress.

Jonathan Fadok

They studied adult female mice in pairs, allowing them to build a stable social interaction over a period of many days. In each pair, one mouse had a high, or dominant, social rank, while the other was labeled a subordinate with a low social standing. They measured changes in behavior, stress hormones, and neural activation in response to prolonged social stress after establishing a baseline.

“We analyzed how these different forms of stress impact behavior and the stress hormone corticosterone (an analogue of the human hormone, cortisol) in individuals based on their social rank,” said Fadok, an assistant professor in the Tulane Department of Psychology and the Tulane Brain Institute. “We also looked throughout the brain to identify brain areas that are activated in response to psychosocial stress.”

“We found that not only does rank inform how an individual responds to chronic psychosocial stress, but that the type of stress also matters,” said Smith-Osborne, a DVM/PhD and the first author on the study.

She discovered that mice with lower social standing were more vulnerable to social instability, which is analogous to constantly changing or inconsistent social groups. Those at higher positions were more vulnerable to social isolation or loneliness.

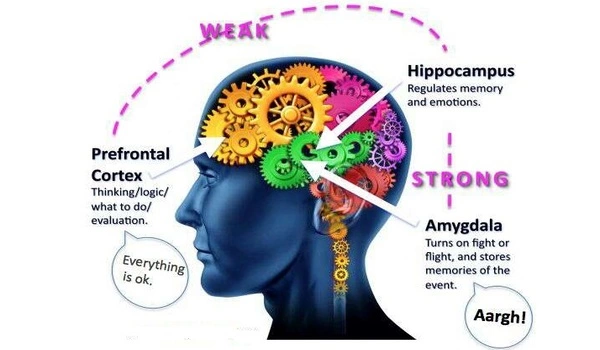

There were also changes in the areas of the brain activated by social contacts based on the social standing of the animal reacting to it and whether or not they had undergone psychosocial stress.

“Some areas of a dominant animal’s brain would react differently to social isolation than to social uncertainty, for example,” Smith-Osborne told the BBC. “The same was true for subordinates.” Rank gave the animals a distinct neurological ‘fingerprint’ for how they behaved to persistent stress.”

Do the researchers believe the findings can be applied to people? Fadok speculated.

“Overall, these findings may have implications for understanding the impact that social status and social networks have on the prevalence of stress-related mental illnesses such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depression,” he added. “However, future studies that use more complex social situations are needed before these results can translate to humans.”