According to a new study led by the University of Bristol and Peking University, emissions of the ozone-depleting chemical dichloromethane from China have more than doubled in the previous decade.

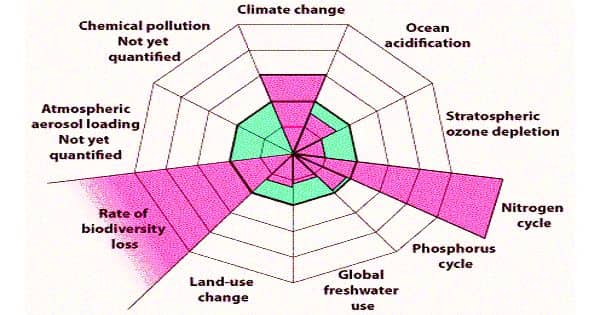

Since the signing of the Montreal Protocol, emissions of the primary chemicals responsible for depleting the stratospheric ozone layer, the layer of the atmosphere that protects us from dangerous solar radiation, have decreased dramatically.

Chemicals that deplete the earth’s protective ozone layer are known as ozone-depleting compounds. They include:

- chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)

- halon

- carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)

- methyl chloroform (CH3CCl3)

- hydrobromofluorocarbons (HBFCs)

- hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs)

- methyl bromide (CH3Br)

- bromochloromethane (CH2BrCl)

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer regulates the production and import of certain substances (the Montreal Protocol). Other ozone-depleting compounds exist, but their ozone-depleting effects are minor, thus the Montreal Protocol does not regulate them.

In comparison to CFCs and other banned ozone-depleting substances, dichloromethane only lasts around six months in the atmosphere. For this reason, unlike longer-lived ozone-depleting chemicals, its manufacture and use are not regulated under the Montreal Protocol.

Dr. Luke Western from the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry said: “International monitoring networks have known that global atmospheric concentrations of dichloromethane have been rising rapidly over the last decade, but until now, it was unclear what was driving the increase.”

Researchers from Peking University, the China Meteorological Administration, and the University of Bristol collaborated to evaluate fresh data obtained in China in order to answer that issue. Their findings were just published in the journal Nature Communications.

International monitoring networks have known that global atmospheric concentrations of dichloromethane have been rising rapidly over the last decade, but until now, it was unclear what was driving the increase.

Dr. Luke Western

The study was led by Minde An, a Peking University postgraduate student and visiting researcher at the University of Bristol.

He said: “China is an important producer and user of compounds such as dichloromethane. Therefore, we wanted to examine measurements within the country to determine its contribution to global emissions.”

“Our calculations revealed that China’s share of total global emissions grew from about one-third to two-thirds over the last decade. The global emissions increase since 2011 is the same size as the rise in emissions from China.”

“We think that emissions of dichloromethane from China have increased because of its use as a solvent in various industrial applications and the expanding chloromethanes industry in China.”

In China, current restrictions on the use of dichloromethane are limited to its toxicity and role in urban air pollution. Dichloromethane levels in consumer products are regulated, and industrial process release rates are limited, but there is no limit on the total amount that can be released into the atmosphere.

Dichloromethane emissions have historically been low enough that experts monitoring ozone layer regeneration haven’t been concerned. However, the recent increase should be closely monitored in the future.

Because no adequate substitute exists, several ozone-depleting chemicals with a significant ozone-depleting potential are nevertheless employed in quarantine and safety applications. As a quarantine fumigant, methyl bromide is particularly effective.

In restricted places such as airplanes and submarines, halon’s immediate fire suppression properties are required. The search for potential replacements is still ongoing.

Dr. Ryan Hossaini from the University of Lancaster, and co-author of the study, said: “If current levels of dichloromethane persist, we could expect to see a delay in ozone layer recovery of a few years. However, if they continue to grow at the rate we’ve seen over the last decade, it could lead to a delay of over a decade, though future emissions are highly uncertain.”

“Of significance is the location of the emissions discovered in this study. Short-lived compounds like dichloromethane are partly destroyed in the lower atmosphere before they reach the ozone layer.”

However, there are areas in Asia where the atmosphere can transport these compounds to the stratosphere very quickly. As a result, emissions from these areas may have a greater impact than emissions from other areas.

Despite these reservations, there are indicators that change is on the way. A draft regulation issued by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment last month identified dichloromethane as a new contaminant whose usage in many industries, including paint stripping and insulating foam production, might be prohibited.

Professor Matt Rigby, also of the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry, expressed optimism that these findings might be replicated in the future to establish the impact of regulatory changes for dichloromethane and other Montreal Protocol-relevant substances.

He added: “One of the most important outcomes of this work is in showing what can be achieved through the close collaboration between scientists from around the world.”

“These measurements from China are highly valuable for researchers and policymakers who are interested in the ozone layer and climate. We’re looking forward to continuing this work in future, to provide the parties to the Montreal Protocol with increasingly accurate information to help ensure that the recovery of the ozone layer stays on track.”