Sri Lanka’s quest to become the world’s first 100 percent organic food producer threatens the country’s prized tea industry and has sparked fears of a larger crop disaster, which could further hamper the country’s already battered economy.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa banned chemical fertilizers this year to kickstart his organic race, but tea plantation owners predict crop failure as early as October, with cinnamon, pepper, and staples like rice also in jeopardy.

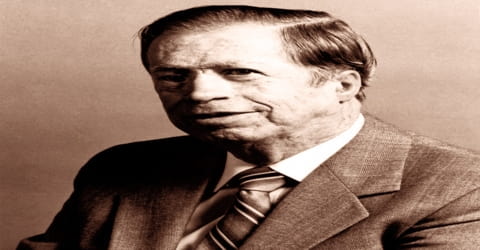

Herman Gunaratne, a master tea maker and one of 46 experts chosen by Rajapaksa to guide the organic revolution, fears the worst. “The ban has thrown the tea industry into disarray,” Gunaratne said at his plantation in Ahangama, which is located in rolling hills 160 kilometers (100 miles) south of Colombo.

The ramifications for the country are unfathomable. The 76-year-old tea farmer fears that Sri Lanka’s average annual crop of 300 million kilograms (660 million pounds) will be cut in half unless the government changes course.

Sri Lanka’s drive to become the world’s first 100 percent organic food producer threatens its prized tea industry and has triggered fears of a wider crop disaster that could deal a further blow to the beleaguered economy.

Sri Lanka is in the grip of a pandemic-induced economic crisis, with GDP falling by more than 3% last year, and the government’s hopes for a return to growth have been dashed by a new coronavirus wave. Fertilizers and pesticides are among a slew of critical imports halted by the government as it battles foreign currency shortages.

Food security ‘compromised’

However, tea is Sri Lanka’s largest single export, bringing in more than $1.25 billion per year and accounting for roughly 10% of the country’s export income. Rajapaksa took office in 2019 promising to subsidize foreign fertilizer but later reversed his position, claiming that agrochemicals were poisoning people.

Gunaratne, whose Virgin White tea costs $2,000 per kilo, was kicked off Rajapaksa’s Task Force for a Green Socio-Economy last month after disagreeing with the president. According to him, the country’s Ceylon tea has some of the lowest chemical content of any tea and poses no risk. The tea crop reached a record 160 million kilos in the first half of 2021 as a result of good weather and old fertilizer stocks, but harvesting began in July.

Sanath Gurunada, who manages organic and traditional tea plantations in Ratnapura, southeast of Colombo, predicts that if the ban remains in place, “the crop will begin to crash by October, and we will see exports seriously affected by November or December.”

He told AFP that his plantation had an organic section for tourists, but it was not profitable. Organic tea is ten times more expensive to produce, and the market is limited, according to Gurunada. Former central bank deputy governor and economic analyst W.A. Wijewardena described the organic project as “a dream with unimaginable social, political, and economic costs.” He stated that Sri Lanka’s food security has been “compromised,” and that the country’s situation is “deteriorating day by day” in the absence of foreign currency.

Jobs at stake

According to experts, the problem with rice is also acute, while vegetable growers are staging near-daily protests over reduced harvests and pest-affected crops. “If we go completely organic, we will lose 50% of the crop, but we will not get 50% higher prices,” Gunaratne explained.

Tea plantation owners claim that, in addition to lost earnings, a crop failure would result in massive unemployment because tea leaves are still picked by hand. “Three million jobs will be jeopardized if tea fails,” the Tea Factory Owners Association said in a statement.

Plantation minister Ramesh Pathirana stated that the government hoped to provide organic compost instead of chemical fertilizers. “Our government is committed to providing something beneficial to the tea industry in terms of fertilizer,” he told AFP. According to farmers, the organic drive will have an impact on Sri Lanka’s cinnamon and pepper exports as well.

According to United Nations figures, Sri Lanka supplies 85 percent of the global market for Ceylon Cinnamon, one of the two leading types of spice. Nonetheless, Rajapaksa remains confident in his strategy, telling a recent UN summit that his organic initiative will provide “greater food security and nutrition” for Sri Lankans. He has urged other countries to take “bold steps” to transform the world food system in the same way that Sri Lanka has.