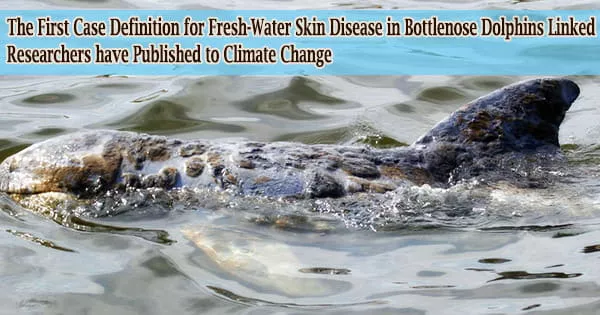

Scientists at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, the world’s biggest marine mammal hospital, and worldwide collaborators have discovered a new skin disease in dolphins connected to climate change.

The research is significant because it is the first time scientists have been able to pinpoint a cause to the sickness that has afflicted coastal dolphin communities around the world since it first surfaced in 2005.

Many aquarium programs feature bottlenose dolphins as intelligent and charismatic stars. Their curved mouths provide the impression of a permanent welcoming smile, and they may be trained to do intricate tricks. The dolphins acquire patchy and elevated skin sores over their bodies as a result of decreased water salinity caused by climate change, which can cover up to 70% of their skin.

Bottlenose dolphins can be found in warm and temperate waters all over the world, with the exception of the Arctic and Antarctic Circles. Dolphins were once heavily hunted for meat and oil (which was used in lamps and cooking), but today only a little amount of dolphin fishing takes place.

Three internationally renowned scientists from California and Australia co-authored the multinational study, which may be accessed here:

- Dr. Pádraig Duignan, Chief Pathologist at The Marine Mammal Center

- Dr. Nahiid Stephens, a veterinary pathologist at Murdoch University (Perth, Australia)

- Dr. Kate Robb, Founding Director, zoologist, and geneticist of the Marine Mammal Foundation (Victoria, Australia)

The study, which was published in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, is the first to give a case definition for fresh-water skin disease in bottlenose dolphins.

As warming ocean temperatures impact marine mammals globally, the findings in this paper will allow better mitigation of the factors that lead to disease outbreaks for coastal dolphin communities that are already under threat from habitat loss and degradation. This study helps shed light on an ever-growing concern, and we hope it is the first step in mitigating the deadly disease and marshalling the ocean community to further fight climate change.

Dr. Pádraig Duignan

This research follows major epidemics in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Texas, as well as Australia, in recent years. An abrupt and significant reduction in salinity in the seas was a common element in all of these places.

Coastal dolphins are used to seasonal salinity fluctuations in their maritime home, but they do not survive in freshwater. Storms like hurricanes and cyclones are becoming more severe and frequent, especially when they are preceded by dry conditions, pouring exceptional amounts of rain that convert coastal waters to freshwater.

Freshwater shortages can last for months, especially in the aftermath of hurricanes Harvey and Katrina. Climate scientists have predicted that as global temperatures rise, catastrophic storms like this will become more common, resulting in more frequent and severe illness epidemics among dolphins.

“This devastating skin disease has been killing dolphins since Hurricane Katrina, and we’re pleased to finally define the problem,” said Duignan. “With a record hurricane season in the Gulf of Mexico this year and more intense storm systems worldwide due to climate change, we can absolutely expect to see more of these devastating outbreaks killing dolphins.”

The research has significant implications for the present outbreak in Australia, which is affecting the rare and endangered Burrunan dolphin in southeast Australia, and might give specialists the knowledge they need to diagnose and treat sick animals.

The long-term outlook for dolphins suffering from skin illness is now bleak. This is especially true for animals that have been exposed to freshwater over an extended period of time.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, researchers discovered the fatal skin illness in about 40 bottlenose dolphins near New Orleans.

“As warming ocean temperatures impact marine mammals globally, the findings in this paper will allow better mitigation of the factors that lead to disease outbreaks for coastal dolphin communities that are already under threat from habitat loss and degradation,” said Duignan.

“This study helps shed light on an ever-growing concern, and we hope it is the first step in mitigating the deadly disease and marshalling the ocean community to further fight climate change.”