Microplastics can be found everywhere, even in the most remote locations. Where do these teeny-tiny shards of plastic come from? According to researchers from the University of Basel and the Alfred-Wegener Institute, precise analysis is required to answer this question.

Microplastics are a problem in the environment because organisms ingest them and can be harmed by them. Even remote areas like Antarctica are affected. A research team from the University of Basel’s Department of Environmental Sciences and the Alfred-Wegener Institute (AWI) at the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research on the island of Heligoland studied water from the Weddell Sea, a region with little human activity, to quantify this type of pollution and determine where the small particles come from.

“This is the first time a study of this scope has been conducted in Antarctica,” says Clara Leistenschneider, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Basel. During two expeditions with the research vessel Polarstern in 2018 and 2019, the researchers collected a total of 34 surface water samples and 79 subsurface water samples. They filtered approximately eight million liters of seawater and discovered microplastics – albeit in very small quantities. The researchers’ findings were published in the journal Environmental Sciences and Technology.

Previous research on microplastics in Antarctica was done in areas with more research stations, shipping traffic, and people. The research team, led by Professor Patricia Holm (University of Basel) and Dr. Gunnar Gerdts (AWI), hypothesized that the remote Weddell Sea would have significantly lower microplastic concentrations. Their measurements, however, revealed that concentrations are only partially lower than in other parts of Antarctica.

This is the first time a study of this scope has been conducted in Antarctica. During two expeditions with the research vessel Polarstern in 2018 and 2019, the researchers collected a total of 34 surface water samples and 79 subsurface water samples. They filtered approximately eight million liters of seawater and discovered microplastics – albeit in very small quantities.

Clara Leistenschneider

Paint and varnish are probably the main sources

It is one thing to establish the presence of microplastics in a specific area. “However, knowing which plastics appear is also important in order to identify their possible origin and, in the best case, to reduce microplastic emissions from these sources,” explains Leistenschneider.

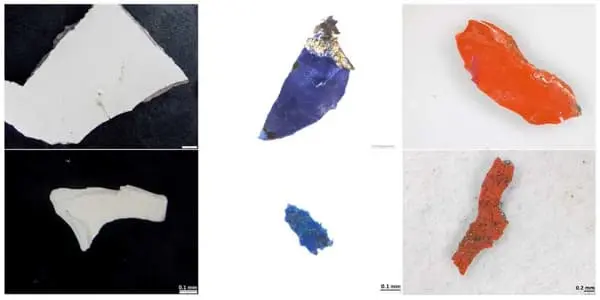

The plastic composition of the particles filtered out of the seawater was first examined by the researchers. They discovered that 47 percent of the microplastic particles were made of plastics that can be used as a binding agent in marine paint. As a result, marine paint and, by extension, shipping traffic are likely to be a major source of microplastics in the Southern Ocean.

Polyethylene, polypropylene, and polyamides were identified as other microplastic particles. These are used in a variety of applications, including packaging materials and fishing nets. Although the different plastics used can be identified, the exact origin or previous application of the microplastic fragments is unknown, according to Leistenschneider.

The additional analysis uncovers new findings

More than half of all sample fragments in this study matched the visual characteristics of the ship painted on the research vessel Polarstern, on which the team was traveling. The researchers at the University of Bremen’s Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (Marum) examined these fragments in greater detail using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to identify pigments and fillers, as the commonly used method, Fourier transform infrared microscopy (FT-IR), failed to identify these substances. They are an important component of paint, along with binding agents, and are analyzed in forensics, along with their plastic content, to identify, for example, cars in hit-and-run accidents. Paint slivers left at the scene of an accident are, in a sense, the vehicle’s fingerprints.

The Bremen analysis revealed that 89 percent of the 101 microplastic particles studied in depth originated from the Polarstern. The remaining 11% was derived from other sources. As a result of this finding, Leistenschneider stated, “A number of comparative methods must be used to determine the origin of paint particles.” This is the only way to tell the difference between paint fragments found in the environment and the contamination caused by the research vessel.

Previous microplastics studies typically excluded particles similar to the paint on their own research vessels as contamination (based on the composition of binding agents and/or visual characteristics) without further investigation.

For several years, shipping traffic in the Southern Ocean has increased, owing primarily to increased tourism and fishing, but also to research expeditions. “Developing alternative marine paint that is more durable and environmentally friendly would allow us to reduce this source of microplastics and the harmful substances they contain,” summarizes Leistenschneider.