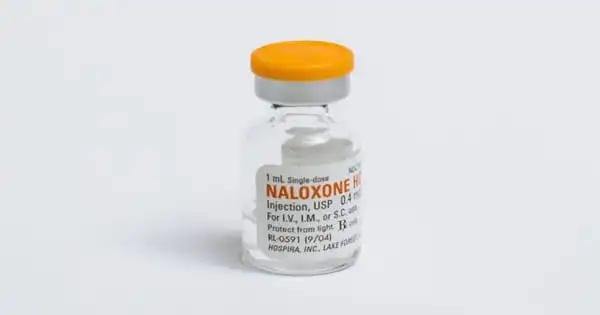

Naloxone is a medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat opioid overdoses. It is an opioid antagonist, which means it binds to opioid receptors and can reverse and block the effects of other opioids like heroin, morphine, and oxycodone.

Because naloxone is so effective at saving the lives of opioid overdose victims, some people are concerned that it will lead drug users to believe that heroin and other similar drugs are no longer dangerous. However, a new study suggests that this is not the case.

Naloxone, a fast-acting medication used to treat respiratory failure, has grown in popularity across the country as a result of the rising number of overdose deaths linked to the drug crisis. Many public health organizations have promoted programs to help people get access to naloxone so they can help people who have overdosed on opioids. However, critics of these programs claim that increasing access to naloxone leads to an increase in drug-related deaths.

It’s really difficult to change people’s perceptions of how dangerous heroin is. Even heroin users are aware that it is dangerous, and access to naloxone hasn’t changed that.

Mike Vuolo

Because naloxone is so effective at saving the lives of opioid overdose victims, some people are concerned that it will lead drug users to believe that heroin and other similar drugs are no longer dangerous. However, a new study suggests that this is not the case. According to the findings, increased access to naloxone did not lead Americans, including drug users, to believe heroin was less dangerous.

“It’s really difficult to change people’s perceptions of how dangerous heroin is,” said Mike Vuolo, study co-author and associate professor of sociology at The Ohio State University. “Even heroin users are aware that it is dangerous, and access to naloxone hasn’t changed that.”

Vuolo collaborated on the study with Brian Kelly, a sociology professor at Purdue University. It appeared in the journal Addiction. Naloxone is a prescription medication that can be used to quickly reverse an opioid overdose by restoring normal breathing in an overdose victim whose breathing has slowed or stopped. It is safe to use because the medication has no effect on people who do not have opioids in their systems.

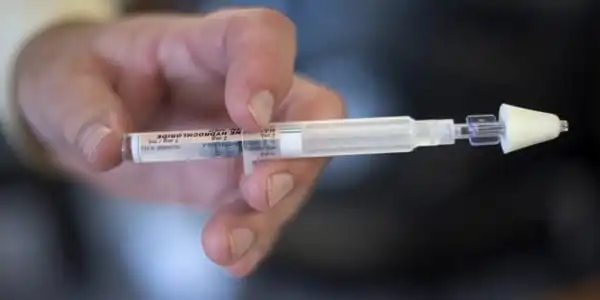

Naloxone is available as a nasal spray, making it simple to use.

The researchers used data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health. They analyzed data from 2004 to 2016, which included 884,800 people aged 12 and up.

On a 4-point scale ranging from “none” to “great risk,” participants were asked to rate the riskiness of heroin use. On the same scale, they were also asked how dangerous they thought regular heroin use was.

The researchers matched people’s responses to naloxone laws in their respective states and counties. During the study period, most states expanded naloxone access beyond healthcare professionals to include other first responders, pain patients, and, in many cases, the general public. Only eight states had expanded access in 2013. By 2017, however, 47 states had enacted some form of naloxone access legislation.

“Expanding public access to naloxone has given regular people hope in their ability to respond to an opioid overdose if they encounter one, especially if they are trained,” Vuolo said.

Some politicians and others have spoken out against the laws, claiming that they will cause drug users to lose fear of using heroin or, worse, encourage young people to start using. However, according to Vuolo, the study found that people’s perceptions of the risks of heroin were consistent in all cases.

Those who lived in areas where easy access to naloxone was required thought heroin was just as dangerous as those who lived in areas where it was prohibited. Those who used drugs, including heroin, did not believe that living in areas with easy access to naloxone made heroin use less risky. Gender, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity had no effect.

And young people’s risk perceptions did not differ based on where they lived. “That suggests that naloxone access laws aren’t encouraging young people to try heroin because they believe it’s less dangerous,” he said.

Fears that naloxone access will lead to increased drug use, according to Vuolo, are similar to concerns that needle exchange programs, which are intended to prevent the spread of diseases from intravenous drug users who share needles, will do the same.

“There was no evidence that these needle exchange programs led to increased drug use, and our study suggests that access to naloxone will not lead to increased drug use,” he said. “We should not be afraid of increasing access to this life-saving medication.” The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the research.