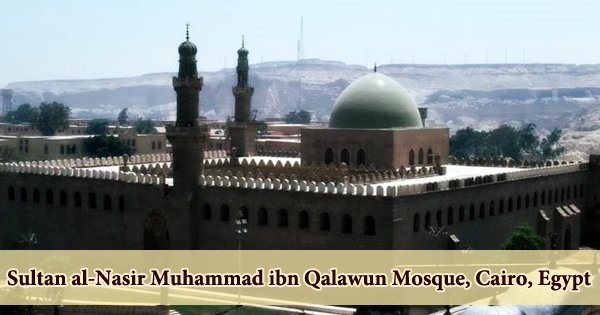

The Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun Mosque, which is located at the Citadel in Cairo, Egypt, is an early 14th-century mosque. The mosque was built as the royal mosque of the citadel by al-Nasir Muhammad in 1318, during his third and longest reign (1309-1340), presumably on the site of the Ayyubid congregational mosque, which al-Nasir Muhammad ordered dismantled and rebuilt. Saladin most likely built the Ayyubid mosque as part of his operations at the citadel.

The mosque is across the street from the Muhammad Ali Mosque’s courtyard entrance. The Sultan also constructed a religious complex in the city’s heart, near to his father’s Qalawun’s. The dome over the prayer niche fell in the 16th century. The mosque was plundered by the Ottoman Turks when they captured Egypt, and most of the marble paneling was taken to Turkey. Until the British took over the government of Cairo in the late 18th century, it remained a neglected construction.

The mosque is a free-standing, rectangular structure with an austere façade that may be explained by the military aspect of its location. It follows the hypostyle plan with a rectangle courtyard with a sanctuary on the qibla side and arcades on the other three sides, as well as the typical pattern of a rectangular courtyard with a sanctuary on the qibla side and arcades on the other three sides. When the mosque was finished in 1318, Sultan al-Nasir utilized it for his daily prayers. The busy sultan had a secluded haven of thought in a side room surrounded by beautiful iron work.

The mosque was built in a hypostyle style, with columns supporting the roof. For the Sultan, there is a side private area surrounded by elaborate ironwork. The armed forces and palace personnel could hear the call to prayer, which was broadcast from the north minaret. The call to prayer was broadcast to the north, where it could be heard by the palace forces. Perhaps for the first time in history, the monies used to construct this mosque exceeded the mosque’s real costs. These revenues were used to expand the mosque’s land and retail space, making it one of the city’s wealthiest institutions.

Marble columns with pre-Islamic capitals support pointed arches with ablaq voussoirs in the sanctuary’s arcades and surrounding the courtyard. A pair of pointed-arched windows are located above each arch. The lower half of the crenellated wall, which was probably erected above the arcades in 1335, is made up of these windows. When the British came in Cairo, the Mosque on the Citadel had outlived its glory days as the Sultan’s preferred site of meditation.

When the Ottomans conquered Cairo, they looted the mosque, removing most of the marble paneling. The walls of prison cells and storage rooms were plastered in the spaces between the massive columns that served as entrances. The structure is square in design and has a central courtyard that can accommodate up to 5000 worshippers. The bulbous sections of the two minarets are beautifully sculpted. Glass mosaics adorn the ceilings, a type of embellishment used widely by Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad in all of the constructions he commissioned. According to Maqrizi, Amir Qawsun commissioned a Tabrizi architect to design his mosque (1329-30), which included two minarets styled after those of Vizier ‘Ali Shah Ghilani’s mosque in Tabriz (none of these exist today).

The Citadel Mosque has been restored to its original state, however various repairs have been undertaken. It is open to the public; however, tourists visit it infrequently. Parts of the structure that rely on plastered walls have been strengthened. There have also been attempts to restore the ceiling’s light-blue tint. Faience mosaics, which are also popular in Ilkhanid Persia, are executed in green, white, and blue on this bulbous top, similar to those on the sabil attached by al-Nasir Muhammad to his father Qalawun’s madrasa (sabil 1326, mosaics probably after 1348), with an inscription band of white faience mosaic around the neck of the bulb.

The mosque is 206 by 186 square feet in size. The center court of the mosque, where prayers are held, is 117 feet 6 inches by 76 feet 6 inches. The crenellations surrounding the base of the eastern minaret’s bulbous top are the first documented use of this technique at the foot of a Cairene dome. The mosque’s principal entrance is a door on the north side. The Sultan’s private entrance would have been the south door, but the eastern and southern entrances were clogged with debris when the British took charge.

The first level of the western minaret’s round shaft has a herringbone or vertical zigzag pattern, while the second level’s round shaft has a horizontal zigzag motif or chevrons. At this mosque, these zigzag designs first occur around the shafts of Egyptian minarets. A message over the doors in flowing Arabic script reads:

“In the name of God the Merciful, the Gracious, He who ordered the building of this mosque, the Blessed, the Happy, for the sake of God, whose name be exalted, is our Lord and Master, the Sultan and King, the conquer of the world and faith, Nasir Mohamed, son of our lord the Sultan Kalaoun es Saleh, in the months and year of Hegira of the Prophet seven hundred and eighteen.”

The western minaret is a continuation of the Cairene practice of building minarets at foundation gates. Its shafts are distinguished from those of the eastern minaret by ornate stone carving due to its location at the western portal, which was the ceremonial entrance facing the sultan’s chambers. The mosque’s walls were built with limestone looted from the pyramids. The mosque’s eleven red granite pillars had also been stolen. In 1335, the mosque’s height was extended, the roof was restored, and a green-tiled wooden dome was erected over the maqsura. It was the Mamluk sultans’ royal mosque where they had their Friday prayers.

According to some scholars, Sultan al-Nasir was friends with the Mongols at the time and may have engaged a master mason from Tabriz to build his mosque’s minarets. It was one of the city’s most impressive mosques until the original tiled wooden dome above the nine-bay maqsura in front of the mihrab fell in the 16th century, and Sultan Selim took the marble dado to Istanbul. The Mosque is exceptional in that the finances available to construct it were greater than the actual cost. It is still used as a place of prayer and is only occasionally visited by visitors.

Information Sources: