Could the existence of the world’s eight billion people have depended on the fortitude of just 1,280 human forebears who nearly went extinct 900,000 years ago?

That is the conclusion of a recent study that employed genetic analytical modeling to discover that our forefathers were on the verge of extinction for nearly 120,000 years.

However, experts who were not part of the study rejected the assertion, with one telling AFP that there was “pretty much unanimous” consensus among population geneticists that it was not compelling.

None denied that human ancestors may have faced extinction at some point due to a population bottleneck.

Experts, however, questioned whether the analysis could be that precise, given the incredibly difficult task of predicting population changes so long ago, and underlined that similar methods had not detected this large population drop.

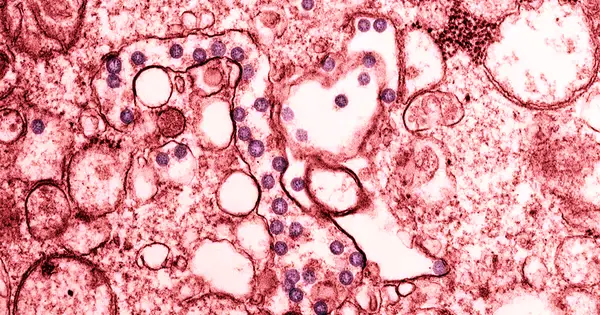

It is incredibly difficult to extract DNA from the few fossils of human relatives dating back hundreds of thousands of years, making it difficult to learn much about them.

Scientists can now evaluate genetic changes in present humans and apply a computer model that works backward in time to estimate how populations changed—even in the distant past—thanks to improvements in genome sequencing.

The study, which was published earlier this month in the journal Science, examined the genomes of over 3,150 modern-day individuals.

The Chinese-led team constructed a model to crunch the figures and discovered that the population of breeding human ancestors decreased to roughly 1,280 around 930,000 years ago.

99 percent annihilation of ancestors?

“About 98.7 percent of human ancestors were lost” during the start of the bottleneck, according to co-author Haipeng Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health.

“Our ancestors almost went extinct and had to work together to survive,” he told AFP.

According to the study, the bottleneck, which was possibly induced by a period of global cooling, lasted until 813,000 years ago.

Then there was a population increase, probably caused by a warming environment and “fire control,” according to the report.

According to the researchers, inbreeding during the bottleneck could explain why humans have a substantially lower amount of genetic diversity than many other species.

According to the study, the population squeeze may have even led to the independent evolution of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans, all of which are assumed to have split from a common ancestor around that time.

It could also explain why there are so few fossils of human ancestors from the time period.

However, archaeologists have unearthed fossils dating from the same period in Kenya, Ethiopia, Europe, and China, suggesting that our ancestors were more widespread than such a bottleneck would allow.

“The hypothesis of a global crash does not fit with the archaeological and human fossil evidence,” said Nicholas Ashton of the British Museum in a statement to Science.

In response, the study’s authors stated that hominins living in Eurasia and East Asia at the time may not have contributed to modern humans’ origin.

“All modern humans are descended from an ancient small population.” “We wouldn’t have the traces in our DNA otherwise,” Li explained.

‘Extremely skeptical’: Stephan Schiffels, population genetics group leader at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told AFP he was “extremely skeptical” that the researchers had accounted for the statistical uncertainty involved in this type of analysis.

Schiffels stated that it will “never be possible” to use genomic study of modern humans to obtain such an exact figure as 1,280 from so long ago, adding that such research typically involves vast ranges of estimates.

Li stated that their range was between 1,270 and 1,300 people, a difference of only 30.

Schiffels further stated that the data utilized in the study has been known for years and that earlier approaches for inferring past population levels had not detected any such near-extinction event.

The study’s authors reproduced the bottleneck using some of these past models, noting their population drop this time.

However, because the models should have detected the bottleneck the first time, “it is difficult to be convinced by the conclusion,” said Pontus Skoglund of the Francis Crick Institute in the United Kingdom.

Aylwyn Scally, a Cambridge University expert in human evolutionary genetics, told AFP that there was “a pretty much unanimous response among population geneticists, people who work in this field, that the paper was unconvincing.”

Our ancestors may have been on the verge of extinction at some point, but modern genomic data’s capacity to infer such an event was “very weak,” he added.