The side effects of large-scale forestation programs could limit CO2 removal advantages by up to a third, according to a groundbreaking study. The study, headed by experts at the University of Sheffield and published in the journal Science, sheds fresh light on the broader effects of forestation on the Earth’s climate, suggesting that its positive impact may be smaller than previously thought.

The IPCC has acknowledged carbon removal tactics such as forestation, as well as initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as critical steps to decrease the risk of disastrous future climate change.

Academics from the University of Sheffield, in collaboration with the Universities of Leeds and Cambridge, as well as NCAR and WWF, discovered that while forestation increases carbon dioxide absorption from the atmosphere, other complex Earth System responses could offset these benefits by up to a third.

Dr. James Weber, principal author of the study from the University of Sheffield’s School of Biosciences, stated: “The public is bombarded with messages about climate change, and the suggestion that you may plant trees to offset your carbon emissions is prevalent. Many companies now offer to plant a tree with each purchase, and some countries intend to increase, maintain, and restore forests.

This study offers a significant contribution by indicating that the combined effects of albedo and atmospheric chemistry from forestation counteract some of the perceived climate-change mitigation benefits of carbon sequestration.

Professor David Edwards

“Trees can help tackle climate change, but we need to be careful about relying on them. We need to evaluate forestation, and other climate change mitigation strategies, in detail. This will help identify limitations and unintended consequences so these can be minimized where possible.”

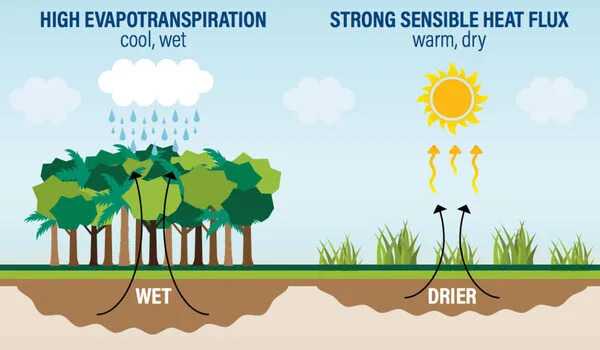

The study, which simulated large-scale forestation under two future scenarios—one with little effort to combat climate change and another with strong mitigation measures in addition to forestation—found that forestation leads to higher CO2 removal. However, it reduces the reflectivity of the land surface (since trees are darker than grassland) and alters the air concentrations of other greenhouse gases (methane and ozone) and microscopic particles known as aerosols. Overall, the indirect consequences partially offset the CO2 reduction gains by up to 30%.

The study also found that when forestation is implemented alongside other strategies to tackle climate change, such as reducing fossil fuel emissions, the negative impacts of these indirect effects are lower. This highlights the importance of combining forestation efforts with complementary climate change mitigation strategies for more effective long-term climate action.

Dr Maria Val Martin, University of Sheffield UKRI Future Leader Fellow and senior author of the study, said: “Drastic CO2 emission reductions along with large-scale removal of atmospheric CO2 are vital to combat climate change effectively. Our study provides a comprehensive analysis of the indirect climate impacts of forestation, revealing that they partially counter the climate benefits achieved through carbon sequestration. Understanding these indirect side effects is essential for developing effective solutions to achieving net-zero emissions.”

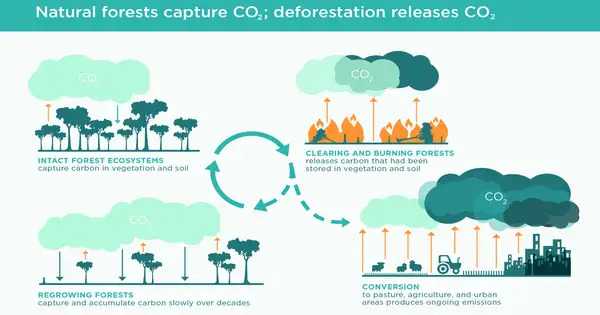

Dr. Stephanie Roe, WWF Global Climate and Energy Lead Scientist, IPCC AR6 Report Lead Author, and co-author of the study said: “We know that forests are critically important for biodiversity, water, ecosystem services, and the climate. What this research shows is that the effectiveness of reforestation for climate mitigation declines significantly in higher latitudes and unless paired with deep emission reductions which reduces air pollution. It underscores the importance of properly planning reforestation efforts and adequately accounting for biophysical and future climate impacts in different latitudes and regions. Importantly, the study finds that preventing deforestation, when compared to reforestation efforts, is a far more efficient way to mitigate climate change.”

Dr Daniel Grosvenor, from the University of Leeds and the Met Office, and co-author of the study said: “What’s interesting about this study is that it examines the side effects of forestation that occur via changes in atmospheric chemistry, aerosol particles and surface reflectivity. It shows that the cooling impact of carbon dioxide removal from an extensive, but feasible, global forest expansion could be considerably reduced due to those side effects. This would make it harder than expected to mitigate climate change and to reach the Paris agreement target.”

Professor David Edwards, Head of Tropical Ecology and Conservation Group at the University of Cambridge, who was not engaged in the study, stated: “Global restoration targets are massive — 350 million hectares by 2030 under the Bonn Challenge alone.” This study offers a significant contribution by indicating that the combined effects of albedo and atmospheric chemistry from forestation counteract some of the perceived climate-change mitigation benefits of carbon sequestration. Critically, the study demonstrates that not all forestation is equal, with more promising prospects in the tropics due to aerosol scattering, which can offset warming caused by reduced albedo, but forestation at higher latitudes may well result in net global warming.”

Professor Dominick Spracklen, Professor of Biosphere-Atmosphere Interactions at the University of Leeds, who was not involved in the study, stated, “This work shows the incredibly intricate role of forests in our climate system. This study, which calculates how forests influence atmospheric composition, provides one of the most complete estimates of the climate implications of large-scale forestation.