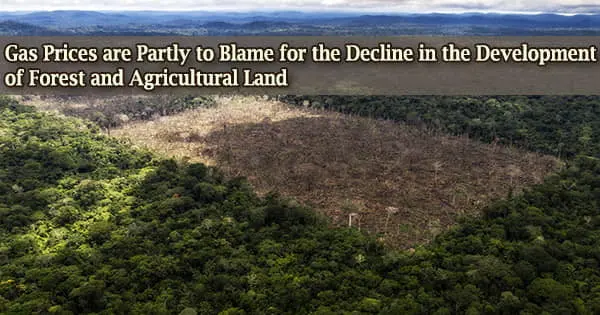

According to a new study, the development of forest and agricultural land decreased dramatically from 2000 to 2015 compared to the previous two decades, resulting in a broad shift toward denser development patterns across the United States. Rising gas prices were a major factor.

Land development was driven by reducing gas prices and, to a lesser extent, growing income levels from 1982 to 2000, according to researchers from Oregon State University, Montana State University, and the United States Forest Service.

Income growth has been static since 2000, but gas prices have risen dramatically. The researchers determined that rises in gas prices, rather than changes in wealth or population, the other two factors they looked at, impacted the current shift toward denser growth the most.

“Increasing gas prices raise commuting costs in areas with longer commutes, which makes land less attractive for housing development in such areas,” said David Lewis, a natural resource economist at Oregon State and co-author of the paper.

In a recently published report in Environmental Research Letters, the researchers called the change in land development patterns as “a remarkable decline” with substantial ramifications for the natural environment, avoiding the development of 7 million acres of forest and agricultural land.

“I think it was surprising that this was occurring partly because it has received hardly any attention,” said Lewis. “It seems to have really flown under the radar that this rate of land development has been declining since the year 2000.”

The speed of land development climbed consistently in the 1980s, peaked in the mid-to-late 1990s, and then began a slow fall around the year 2000, according to the researchers. Around 2010, the pace of development reached a plateau, accounting for less than a fourth of the high rate of the 1990s.

Land development is irreversible, so once land gets developed it generally is not going back to forest or the agricultural use that it was previously. That’s why this is such an important issue to so many people and so many groups because it’s not something that can be undone.

Daniel Bigelow

Land development rates began to decline well before the Great Recession of the late 2000s. This tendency has been confirmed or suggested in other studies, but the causes and effects of the transition have not been thoroughly investigated.

The researchers in the current report conducted a more in-depth look, examining several aspects of land development, with a particular focus on population increase, income fluctuations, and commute costs.

Among their findings:

- The pace of development of the four land categories they analyzed (forest, crop, pasture, and range) in 2015 (0.47 million acres per year) was less than a fourth of the high development rate of 1992-1997. (2.04 million acres per year).

- The transition to denser development patterns happened across the United States, with 83 percent of the 2015 U.S. population living in areas that were denser between 2000 and 2015, compared to 1982 to 2000.

- Over the research period, 90 percent of counties with any developed land area and all but one state (Nevada) had developed areas that became more densely populated.

- Between 2000 and 2015, avoided deforestation amounted to 3.56 million acres, with the majority located east of the Mississippi River or along the Pacific coast.

- The Northeast/Midwest and Southeast regions saw the most avoided farmland loss, totaling 2.06 million acres.

The researchers created a county-level data set of land development patterns for the 48 contiguous US states using data from the US Department of Agriculture’s National Resources Inventory from 1982 to 2015, the most recent year for which data was available. The study did not cover Hawaii or Alaska.

The findings point to a possible link between land development patterns and initiatives to price carbon emissions in order to combat climate change, according to the researchers.

The new research findings indicate how carbon pricing would indirectly conserve forest and agricultural lands by decreasing land expansion since gas prices would rise if carbon emissions were charged.

The study had some flaws, according to the researchers, including the fact that it did not specifically model the impact of land-use rules. They also point out that the findings may not be indicative of a broader worldwide trend in land development.

Perhaps most crucially, they claim that the current lower trend in land development is not a permanent shift. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, has sparked conjecture that it may cause a shift in people’s preferences for living from high-density to lower-density locations, putting further pressure on developers to develop more property in places already characterized by less crowded development patterns.

They hope that this study will pave the way for future research into land development in the aftermath of the pandemic and other major economic shocks.

“Land development is irreversible, so once land gets developed it generally is not going back to forest or the agricultural use that it was previously,” said Daniel Bigelow, a co-author of the paper and a natural resource and agricultural economist at Montana State University. “That’s why this is such an important issue to so many people and so many groups because it’s not something that can be undone.”

Christopher Mihiar with the U.S. Forest Service is also a co-author of the paper. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Agriculture and Food Research Initiative and the U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station helped fund the research.