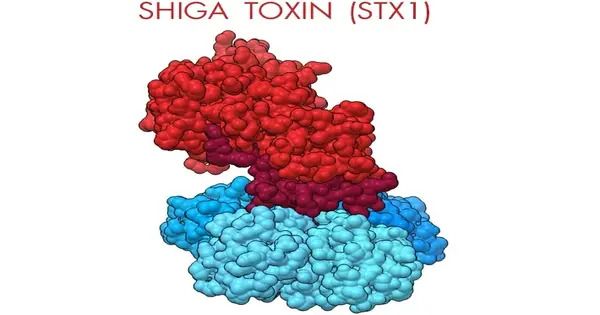

Shiga toxins are a series of similar toxins divided into two primary families, Stx1 and Stx2, which are expressed by genes thought to be found in lambdoid prophages’ genomes. These are strong poisons generated by specific strains of bacteria, particularly Escherichia coli (E. coli). The toxins are named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who was the first to describe the bacterial cause of dysentery, Shigella dysenteriae. These toxins are named after Japanese bacteriologist Kiyoshi Shiga, who discovered them in 1898 while researching the etiology of dysentery.

Shiga toxins are categorized into two types: Stx1 and Stx2. These toxins induce the severe symptoms associated with E. coli infections, particularly serotype O157:H7. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) infections can cause mild diarrhea to serious consequences such as hemorrhagic colitis (bloody diarrhea) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which can be fatal.

Shiga-like toxin (SLT) is a historical term for Escherichia coli toxins that are similar or identical. The bacteria S. dysenteriae and various Escherichia coli (STEC) serotypes, including O157:H7 and O104:H4, are the most common donors of Shiga toxin.

How it Works?

The toxins function by blocking protein synthesis in intestinal cells, causing damage and inflammation. They can also enter the bloodstream and harm other organs, such as the kidneys, resulting in additional difficulties.

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli infections are usually spread through contaminated food or water, notably raw ground beef, unpasteurized dairy products, contaminated fruit, and recreational water sources. Person-to-person transmission can also occur, particularly in childcare institutions and nursing homes.

Prevention

Preventing Shiga toxin-producing E. coli infections involves practicing good food safety measures, such as thorough cooking of meats, proper washing of produce, and avoiding unpasteurized dairy products. Additionally, maintaining good hygiene, especially handwashing, can help prevent the spread of these bacteria.