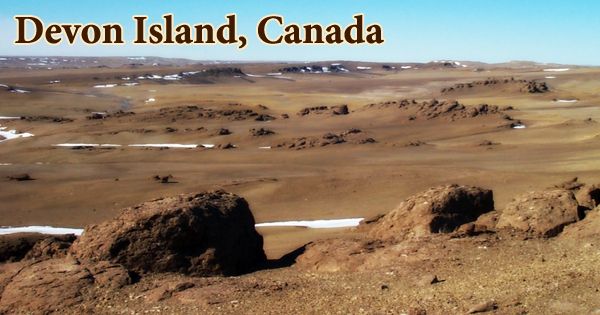

Devon Island (Inuktitut: ᑕᓪᓗᕈᑎᑦ, Tallurutit) is the largest of the Parry Islands in the Arctic Ocean, south of Ellesmere Island and west of Baffin Bay, in Nunavut, Canada. It is the world’s largest uninhabited island (no permanent occupants) and is located in Canada. For good cause, this island in the Baffin Bay, part of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is the world’s largest uninhabited island. The ground is frozen for virtually the entire year, especially in the eastern section of the island, which is perpetually covered by a 500-700-meter-thick ice sheet. It stretches for around 320 miles (515 kilometers), is 80–100 miles (130–160 kilometers) wide, and covers a total area of 21,331 square miles (55,247 square km).

During the height of summer, the ground is snow-free for a brief period of 45-50 days. The average yearly temperature is -16°C, and the summer temperature hardly rises above 8°C. The island is one of the Arctic Archipelago’s largest members, the second-largest of the Queen Elizabeth Islands, Canada’s sixth-largest island, and the world’s 27th-largest island. The island rises from around 2,000 feet (600 meters) in the west to a maximum elevation of 6,300 feet (1,920 meters) in the east, primarily as an ice-covered plateau. Grinnell Peninsula protrudes northwest and has fjordlike inlets on its southern coast.

Robert Bylot and William Baffin discovered the island in 1616, and W.E. Parry called it North Devon after Devon, England. Precambrian, Cambrian, and Ordovician siltstones and shales are found in the east, and Ordovician and Silurian siltstones and shales are found in the west. The Devon Ice Cap, which is part of the Arctic Cordillera, is the highest peak at 1,920 meters (6,300 feet). The Treuter Mountains, Haddington Range, and the Cunningham Mountains are only a few of Devon Island’s tiny mountain ranges. The striking resemblance of its surface to that of Mars has piqued scientists’ interest.

Although there is evidence of Paleo-Eskimo settlement by the Dorset and Thule cultures dating back thousands of years, Devon has only been inhabited twice in recorded history: once in the 1930s by resettled Inuit hunters (who left because it was too cold for them!) and again in the 1940s by Mounties (who left when their harbor got iced in). In 1819–20, William Edward Parry mapped the island’s south shore and named it North Devon, after Devon in England. By the end of the century, the name had been modified to Devon Island. Edwin De Haven sighted the Grinnell Peninsula while sailing along Wellington Channel in 1850.

Devon Island, in other terms, is a desolate wasteland dominated by frost-shattered rocks and devoid of flora and animals. Devon Island, on the other hand, is a fascinating destination for scientists and researchers. Its severe climate and arid terrain are eerily comparable to those on Mars. The Truelove Lowland portion of the island contains diversified vegetation and wildlife, a lot of soil water in the summer due to obstructed drainage, and higher precipitation and summer temperatures (4° to 8°C) than other parts of the island, as well as more clear days.

Temperatures rarely reach 10 °C (50 °F) during the short growing season (40 to 55 days), and can drop to as low as -50 °C (-58 °F) in the winter. Devon Island has a polar desert ecosystem and receives very little precipitation. Since 2001, Devon Island has been home to a group of people working on the Haughton Mars Project (HMP), an international research project that examines how human explorers might live and work on other planetary bodies, particularly Mars. Plants make up the majority of the living species in this system (98.9%), with herbivores and carnivores, soil bacteria, fungus, and invertebrates decomposing the organic matter making up the rest.

Even though it’s cold and frosty, the Canadian Arctic is too frigid for much snow, and Devon Island’s high latitude and high elevation combine to make it a real desert. The black guillemot and northern fulmar concentrations at Cape Liddon make it an Important Bird Area (IBA). Another IBA site, Cape Vera, is known for its northern fulmar population. The lowlands are poorly drained, which encourages the growth of moss, which Musk-Oxen graze all year. Invertebrates such as worms, protozoa, midges, and fly larvae live in the chilly, moist soil.

Devon Island is also known for the Haughton impact crater, which was formed 39 million years ago when a meteorite with a diameter of 2 km (1.2 mi) collided into what were then woods. The impact created a 23-kilometer-wide (14-mile-wide) crater that served as a lake for millions of years. The incident was so powerful that it brought rocks from 1.7 kilometers below the earth to the surface. Weathering is negligible because there is no moving water due to the freezing temperatures. As a result, Haughton maintains many geological features that have been lost to erosion in other craters. The terrain around the Haughton impact crater is thought to be one of the most Mars-like on the planet.

The 15-25 muskoxen that graze in the summer and 60-125 that graze in the winter in this small oasis in the High Arctic are clearly more vital in the operation of this system than the microscopic insects and other soil creatures. The Arctic Institute of North America manages the Devon Island Research Station, which was established in 1960. It is located in Truelove Lowland, on the northeast coast of Devon Island (75°40′N 84°35′W). Plants and animals on the island grow slowly and have a long life cycle due to the island’s short growing season (40-55 days) and low daily summer temperatures (2° to 8°C).

The arid, rocky topography of Devon Island doesn’t support much life, but there’s enough sedge and lichen to support a tiny herd of musk ox, which attract the occasional polar bear onshore. Many invertebrates that take a few weeks to a year or two to complete their life cycle in temperate climates take 2-9 years to finish their life cycle at these latitudes. While the basic ecosystem components of a Saskatchewan grassland or an Ontario hardwood or coniferous forest are similar to those found in the High Arctic, the diversity of species, rates of organismic growth, and levels of ecosystem production are greatly reduced due to the limited solar-energy input into these cold and nutrient-deficient systems near the poles.

Information Sources: