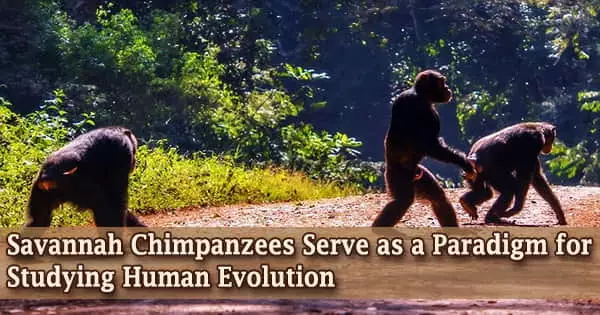

Except for rare populations of chimpanzees that live in savannahs, which have high temperatures and limited seasonal rainfall, most great apes require lush forests in Africa (bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas) or Southeast Asia (orangutans) to thrive.

Adriana Hernández, a Serra Hunter professor at the University of Barcelona’s Faculty of Psychology, was one of the co-leaders of an international team of primatologists who reviewed existing research on savannah chimpanzee behavior and ecology in order to better understand how these apes adapt to extreme conditions.

The study on savannah chimpanzees and what we call the landscape savannah effect have important implications for reconstructing the behavior of the first hominis who lived in similar habitats and therefore, it helps us to better understand our own evolution.

Adriana Hernández

According to the researchers, the environmental conditions in these areas would cause these chimps to engage in specific behaviors and physiological responses, such as resting in caves or digging for water, that are not seen in their counterparts who live in more forested areas and are not exposed to these extreme environmental conditions.

“The study on savannah chimpanzees and what we call the landscape savannah effect have important implications for reconstructing the behavior of the first hominis who lived in similar habitats and therefore, it helps us to better understand our own evolution,” notes Adriana Hernández, who co-led the study, published in the journal Evolutionary Anthropology, together with Stacy Lindshield, from the University of Purdue (United States).

The genetically closest-to-humans evolutionary living relative

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are our closest living cousins, sharing 98.7% of our DNA and sharing a common ancestor that lived between 4.5 and 6 million years ago. Despite their close proximity, they lack some of the biological and cultural characteristics that allow humans to adapt to intense heat, such as abundant eccrine sweat glands, a lack of hair, and the capacity to build artifacts like water containers and sun caps to prevent dehydration and sunstroke.

The chimpanzees that dwell in the savannah are taxonomically interchangeable with other chimps. When a result, behavioral, morphological, and ecological comparisons with chimpanzees living in more wooded areas give critical information for hypothesizing how early humans may have adapted millions of years ago as African forests receded and savannahs took their place.

“We know that early hominins adapted to savannah environments similar to those occupied by chimpanzees today, and researchers think that savannah conditions caused adaptations in our ancestors, such as brain expansion or tolerance to high temperatures,” says Adriana Hernández, who is also the co-director of research at the Jane Goodall Institute Spain.

“Understanding how our genetically closest living relatives adapt to a dry, hot, seasonal, and open environment, similar to those in which early hominins lived, helps us model how our ancestors would have adapted and how the qualities that distinguish us as humans might have arisen, she says.”

Strategies to adapt to high temperatures

Among the many traits of savannah chimps outlined in the paper, their tactics for dealing with extreme heat stand out. “Understanding how they deal with heat can help us better understand what strategies human ancestors may have used to cope with high temperatures. Some strategies are probably the same for chimpanzees and hominins, such as the use of caves or going into water pools to cool down,” notes the researcher.

Another example cited by the researcher is how these chimps attempt to hydrate themselves during the advanced dry season, such as digging for water when this resource is limited to only a few sites throughout the terrain. “Early hominins also had to deal with low water availability during part of the year,” Hernández adds.

Groups distributed over larger areas

The study also found that chimpanzee social groups in the savannah are spread out over abnormally vast regions of over 100 km2, whereas chimpanzees in forested settings had ranges of between 3 to 30 km2. “However, although group sizes are similar in different habitats, chimpanzees in the savannah have a much lower population density, which could be explained by the low availability of food in this habitat.”

Despite the fact that we now know a lot more about savannah chimps than we ever did, their actual numbers are unclear, while the researchers claim that “there are less than those living in forest regions since the overall area they inhabit is significantly smaller.” Furthermore, because they have a lower population density than the forest, there are much fewer people in regions of the same size.

“It should be noted that there are far fewer sites where savannah chimpanzees have been studied, as there are only two study sites where savannah chimpanzees are habituated to humans and their behavior can be observed directly. In contrast, there are many study sites where chimpanzees are fully habituated to researchers in the forest, a habitat where these primates have been studied for decades,” explains Adriana Hernández.

Keys to understanding adaptation to climate change

Another significant addition of this research is that it aids in the comprehension of the possible consequences of climate change on species. “The adaptation of savannah chimpanzees to extreme climates can help us model how chimpanzees that currently inhabit forests might adapt to changes that climate studies project will make their environments drier and warmer. This is important, since the species is categorized as Endangered and the West African subspecies (Pan troglodytes verus) is Critically Endangered,” says the expert.

Given that climate forecasts indicate to “an increase in hotter and drier locations in the future,” the researchers advocate for “further study into the biological and cultural components underpinning the influence of the savannah environment.”