Researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) have discovered a key enzyme that contributes to eczema, which could lead to better treatment to prevent the skin disorder’s debilitating effects. The results of the study were published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Eczema weakens the skin’s protective barrier, making it more vulnerable to foreign entities that can cause itching, inflammation, dryness, and further breakdown of the skin’s protective barrier. Researchers discovered that by genetically modifying Granzyme B or inhibiting it with a topical gel, they could prevent it from damaging the skin barrier and significantly reduce the severity of Alzheimer’s disease.

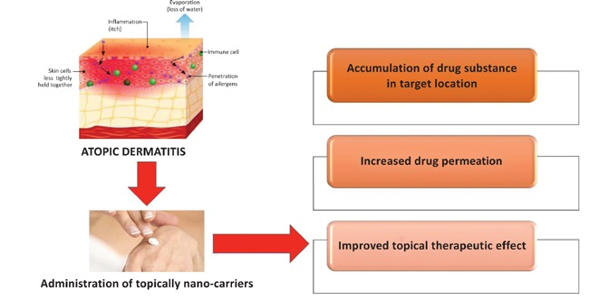

Eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis (AD), weakens the skin’s protective barrier, making it more vulnerable to foreign entities that can cause itching, inflammation, dryness, and further breakdown of the skin’s protective barrier.

Researchers have identified a key enzyme that contributes to eczema, which may lead to a better treatment to prevent the skin disorder’s debilitating effects.

“The symptoms that people frequently experience with eczema make them more likely to avoid leaving their homes or going to work,” says the study’s senior author, Dr. David Granville, a professor in UBC’s faculty of medicine and a researcher at VCHRI. “The annual cost of eczema in North America is estimated to be more than $5.5 billion due to the impact it has on people’s health and well-being.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common cutaneous condition marked by disruption of the epidermal barrier, severe skin inflammation, and pruritus. As we gain a better understanding of disease pathogenesis, the therapeutic arsenal for managing Alzheimer’s disease is rapidly expanding.

In eczema, the Granzyme B enzyme is associated with itching and disease severity. Researchers discovered that Granzyme B weakens the skin barrier by cleaving through the proteins that hold cells together, allowing allergens to pass through.

“Proteins that anchor our skin cells tightly together,” explains Granville. “In some inflammatory diseases, such as eczema, cells secrete Granzyme B, which eats away at those proteins, causing these bonds to weaken and the skin to become more inflamed and itchy.”

Researchers discovered that by genetically modifying Granzyme B or inhibiting it with a topical gel, they could prevent it from damaging the skin barrier and significantly reduce the severity of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Previous research had suggested that Granzyme B levels correlate with the degree of itchiness and disease severity in patients with atopic dermatitis; however, there was no evidence that this enzyme played any causative role,” Granville explains. “Our findings suggest that topical drugs targeting Granzyme B could be used to treat eczema and other types of dermatitis.”

Researchers aim to quell the root cause of eczema symptoms

Approximately 15-20% of Canadians have some form of Alzheimer’s disease, and AD affects 10-15% of Canadian children under the age of five. Around 40% of those will have symptoms of the disease for the rest of their lives.

Alzheimer’s disease is also linked to an increased risk of developing a variety of other inflammatory conditions, such as food allergies, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. Dr. Chris Turner, the study’s lead author and former UBC postdoctoral fellow in Granville’s laboratory, says, “Atopic dermatitis is the leading non-fatal health burden attributable to skin diseases.”

AD is typically characterized by an itch-scratch cycle, in which itchiness is followed by scratching and more itchiness. This cycle typically occurs during flare-ups, which can occur at any time and can occur weeks, months, or years apart. Corticosteroid creams are a common treatment for people with Alzheimer’s disease who have severe itching and rashes. However, if used for an extended period of time, these can thin the skin, making it more prone to damage and infection.

A gel or cream that inhibits or limits Granzyme B, reducing the severity of Alzheimer’s disease, could be a safer and more effective long-term treatment. “A gel or cream that inhibits Granzyme B could have fewer, if any, side effects and avoid the itch-scratch cycle, making flare-ups less severe,” Turner says.

While a commercially available treatment is still a long way off, the researchers see great promise in this area of research and are conducting additional clinical trials on Granzyme B and Granzyme B inhibitors.