Everyone has experienced how dreams can impact our moods and actions at some point in their lives. Putting an idea in someone else’s head while they are dreaming in order to make them do something specific when they wake up, on the other hand, is still science fiction. In the 2010 film “Inception,” Leonardo di Caprio’s character attempts to persuade the heir of a wealthy businessman to dismantle his father’s corporation. To accomplish this, he shares a dream with the heir in which the heir’s ideas about his father are gently altered through skilled manipulation, causing him to forsake his late father’s firm.

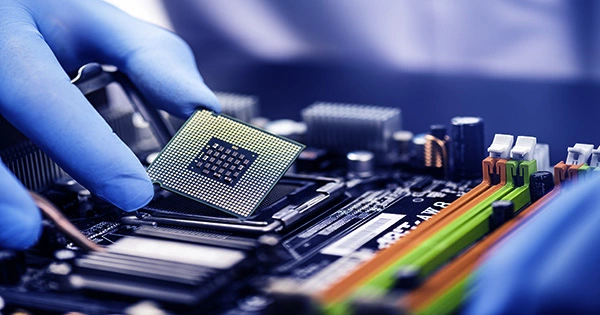

While it is hard to share visions and plant such concepts in reality, something quite similar has just been accomplished in the realm of computers. A team of researchers led by Kaveh Razavi, professor in the Department of Information Technology and Engineering at ETH Zurich, has demonstrated a serious vulnerability of certain CPUs (central processing units) through which an attacker can plant the equivalent of an idea in a victim’s CPU, coax it into executing certain commands, and thus retrieve information. This week, Razavi and his colleagues will report their findings at the USENIX Security 2023 conference.

A complex attack

While the names of Razavi’s study paper are reminiscent of James Bond and disaster movies—”Spectre” and “Meltdown” appear—the majority of it is complex computer science.

“In fact, much like the movie of the same name, the Inception attack is particularly complex and difficult to explain,” explains master’s student Danil Trujillo, who discovered this novel attack while working on his thesis in Razavi’s lab under the supervision of Ph.D. student Johannes Wikner.

“Still,” Wikner continues, “the crux of the matter with all of these attacks is rather simple—namely, the fact that a computer’s CPU has to make guesses all the time, and those guesses can be tampered with.”

Guesses are required in modern computers because the CPU must make hundreds of millions of decisions every second while running a program—say, a game or a web browser. At various times during execution, the following instruction may be dependent on a decision made based on information that must be obtained from the computer’s memory. In recent years, CPUs have become tremendously fast, but the speed at which data can be transported from memory (DRAM) to the CPU has not kept up with that acceleration. As a result, the CPU would have to spend a significant amount of time waiting for new data before making a decision.

Speeding up by guessing

This is where the speculation comes into play: The CPU generates a kind of look-up table based on previous experience and utilizes it to make a guess as to the most likely next step, which it then executes. In the vast majority of cases, the CPU is correct, saving a significant amount of precious computational time. However, it occasionally makes the incorrect guess, which an attacker can use to obtain access to critical information.

“The Spectre attack, discovered in 2018, is based on such miscalculations,” Razavi continues, “but at first it appeared that manufacturers had found ways to mitigate it.” In fact, chip manufacturers have included features for partially deleting the look-up table when switching security contexts (that is, when the computer’s sensitive kernel is accessed) or adding a bit of information that tells the CPU whether or not a prediction in the look-up table was created in the kernel and can thus be trusted.

Planting an idea in a CPU

Nonetheless, Razavi and his colleagues set out to see if an attack could be launched despite the improved protection measures. “It looked as though we could make the CPUs manufactured by AMD believe that they had seen certain instructions before, whereas in reality that had never happened,” Trujillo adds. The researchers could plant a concept in the CPU while it was dreaming, much like in the movie.

As a result, the look-up table—which the CPU constantly generates from previous instructions—could be modified once more. Because the CPU was convinced that the entries in the look-up table came from previous instructions, the security mechanism that was supposed to ensure that only trustworthy predictions were considered was evaded. The ETH researchers were able to leak data from anywhere in the computer’s memory in this manner, including critical information like the hash of the root password.

Serious vulnerability

That is, of course, a very significant security issue, therefore Razavi notified AMD in February to ensure they had enough time to develop a solution before the study article was released (AMD assigned the vulnerability the number CVE-2023-20569).

“We demonstrated the concept of a new class of dangerous attacks, which is especially relevant in the context of cloud computing, where multiple customers share the same hardware,” Razavi says. “It also raises future questions.” For example, he wants to know if there are more, comparable assaults and if a “Inception”-style attack is conceivable on CPUs from other manufacturers.