The researchers compared a new genetic animal model of Down syndrome to the standard model and discovered that the updated version was superior. When compared to a previously studied Down syndrome mouse model, the new mouse model exhibits milder cognitive traits.

Researchers from the National Institutes of Health compared a new genetic animal model of Down syndrome to the standard model and discovered that the updated version was superior. When compared to a previously studied Down syndrome mouse model, the new mouse model exhibits milder cognitive traits. The findings of this study, which were published in the journal Biological Psychiatry, may aid researchers in developing more precise treatments to improve cognition in people with Down syndrome.

The new mouse model, known as Ts66Yah, was discovered to have memory problems and behavioral traits, but the symptoms were not as severe as those seen in the previous mouse model. Scientists frequently use different strains of mice as animal models to study human diseases because most human genes have mouse counterparts.

A mouse model that more precisely captures the genetics of Down syndrome has important implications for human clinical trials aimed at improving cognition.

Diana W. Bianchi

“A mouse model that more precisely captures the genetics of Down syndrome has important implications for human clinical trials aimed at improving cognition,” said Diana W. Bianchi, M.D., director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, senior investigator in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Center for Precision Health Research, and study senior author.

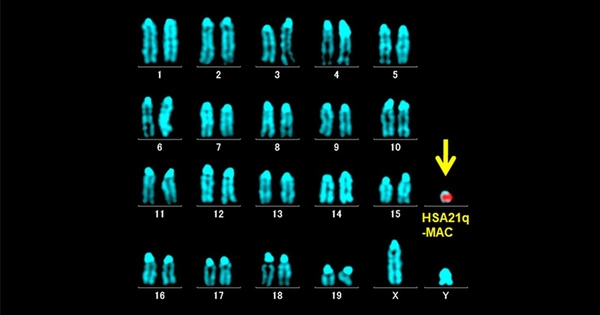

Each year, approximately 6,000 newborns in the United States are diagnosed with Down syndrome. Most of these children have a third copy of chromosome 21. An extra copy of over 200 protein-coding genes is added to that person’s genome, causing difficulties with learning, speech, and motor skills.

For nearly 30 years, a previous mouse model known as Ts65Dn was considered the gold standard for Down syndrome research and was used in preclinical studies. Along with some successful cognitive treatments, such as a recent hormone-based cognitive treatment, some other treatments that worked in mice did not work as well in humans.

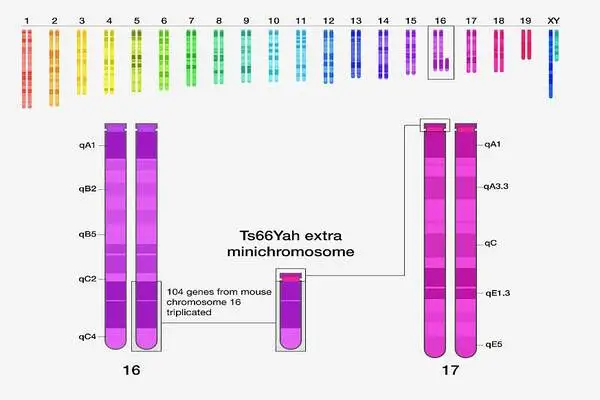

Importantly, the previous mouse model’s genome contains 45 extra genes that are irrelevant to human Down syndrome, as a result of the model’s development process. Humans and mice have very similar genomes, but the chromosomes that comprise those genomes do not exactly align between the two species. Many of the genes found on human chromosome 21 can also be found on mouse chromosomes 16 and 17. The previous mouse model included an extra region of mouse chromosome 17 with 45 extra genes not found on human chromosome 21. Until now, no one has investigated how these 45 extra genes affect the brain and behavior of previous Ts65Dn mice.

To create an enhanced mouse model of Down syndrome, researchers at the University of Strasbourg, France, removed these extra 45 genes using CRISPR gene-editing technology. Dr. Bianchi’s group then compared the two mouse models and found that the extra 45 genes in the previous mouse model were affecting brain development and contributed to more severe difficulties with motor skills, communication and memory.

“These extra genes have significant effects on mouse brain development and behavior,” said Faycal Guedj, Ph.D., a staff scientist in NHGRI’s Center for Precision Health Research and the study’s first author. “What was previously thought to be the best mouse model of Down syndrome has traits derived from genes unrelated to human chromosome 21.”

The Center for Precision Health Research’s researchers hope to foster next-generation healthcare by utilizing cutting-edge genomics tools. Dr. Bianchi’s group hopes to develop more precise treatments for improving cognition in people with Down syndrome using this new and improved mouse model.

“The possibility of treating intellectual disabilities in the context of Down syndrome goes to the heart of changing perceptions about the nature of disability, its medical and clinical aspects, and what we, often pejoratively, consider ‘normal’ and ‘desirable’ in the context of medical care and in society,” says NHGRI senior historian Christopher R. Donohue, Ph.D.

“As cognitive treatments based on genetic models become more feasible in the future, researchers should carefully weigh potential benefits versus drawbacks, such as contributing to ableism in medicine and other forms of stigma, in consultation with disability ethicists, those with Down syndrome, and other healthcare professionals.”