According to a joint study by the Paris-Saclay Neuroscience Institute, Neurospin, and a researcher from the Institute of Psychology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, rats can learn from their prior activities to perfect their skills and timing.

Rats, like humans, can estimate temporal errors in their behaviors. This revelation opens up new opportunities for uncovering the mechanisms and brain structures that underpin the internal representation of time.

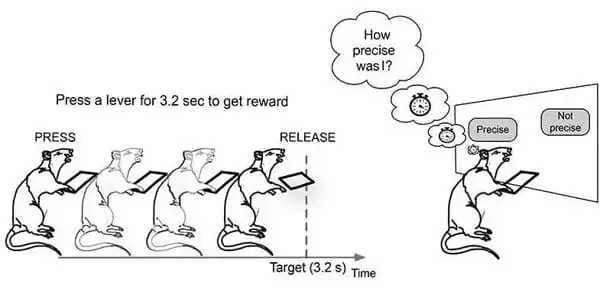

A partnership of French and Polish researchers has proven that rats can assess the passage of time and judge how well they performed while completing a job. Researchers from France’s Institut des Neurosciences Paris-Saclay and Poland’s Academy of Sciences devised a challenge in which rats were taught to press a lever for at least 3.2 seconds in order to obtain a reward.

Humans can estimate the time of their actions due to their capacity for introspection. When they complete a task, especially a timed task, they can evaluate their performance and correct themselves to do better the next time. This talent is not limited to humans: fresh research has been shown for the first time that rats can do it as well!

Rats, like humans, can estimate temporal errors in their behaviors. This revelation opens up new opportunities for uncovering the mechanisms and brain structures that underpin the internal representation of time.

These findings were achieved in a collaborative study conducted by researchers from the Institut des neurosciences Paris-Saclay (CNRS/Université Paris-Saclay), Neurospin (CEA), and a researcher from the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Psychology.

It is not always simple to predict how long a task will take. Unless, of course, you’re a rat. According to a recent multinational study, these rats can evaluate their performance and adjust their behavior to perform better the next time.

Scientists devised a behavioral experiment that required rats to press a lever for at least 3.2 seconds. In a subsequent phase, two feeders delivered a reward based on the animal’s performance: if it performed the task with a tiny error, just over 3.2 seconds, it received food in the left feeder, and if there was a bigger departure, it received food in the right feeder (1). As a result, the rats learnt that the placement of the reward was dependent on their accuracy.

In a third step, the rodents were offered the option of either feeder, but the incentive was only supplied after they chose one. As a result, the rats chose the correct side, i.e. the one corresponding to their temporal error — “precise” for the left-hand feeder or “not precise” for the right-hand feeder, and, sure that they would find food there, they did so even faster.

The researchers explain this behavior by the animals’ previous experience (a track record of rewards obtained), but also by the rats’ analysis of their performance: during each trial, the rodents evaluated the precision with which they had completed the task requested and were able to engage in “error monitoring.”

The researchers discovered that the rats evaluated the precision with which they accomplished the task on each trial. They were even able to calculate their margin of error. Rats, contrary to popular belief, are extremely intelligent animals. Their good episodic memory enables them to recall many different pieces of information from previous encounters. They are even capable of solidarity and generosity, as proven by two distinct investigations undertaken by experts in Japan and academics from the University of Chicago.

The demonstration of this ability in rats opens the door to new types of animal study to better understand these human behaviors. What is the brain’s method for evaluating temporal errors? This important question in neuroscience lies at the heart of the learning process. Future studies will be able to improve fundamental understanding of the mechanisms and brain structures involved in our internal representation of time.

The reward was also placed in a different location based on the rat’s timing accuracy, and they learned to go to one area or another by analyzing how precise their timing had been, which was often within milliseconds of the specified time. The researchers intend to use this knowledge to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms that animals and humans use to assess the passage of time.

Notes

1- Error thresholds were adjusted for each rat, depending on the performance of each animal.