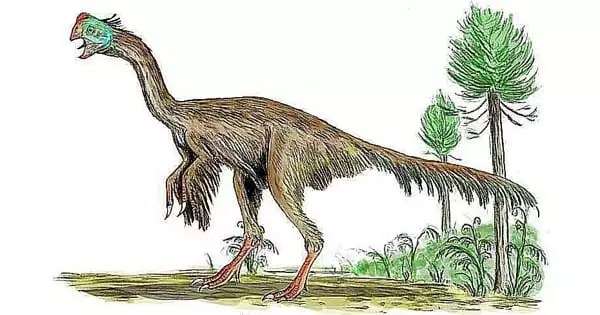

The Regent Honeyeater is a medium-sized, black and yellow honeyeater with a strong, curved bill. Adults weigh 35 to 50 grams, measure 20 to 24 cm in length, and have a 30-centimeter wingspan. It has a black head, neck, throat, upper breast, and bill, and a pale lemon back and lowers breast with a black scalloped pattern. The edges of its flight and tail feathers are bright yellow. Around the eye, there is a distinctive patch of dark pink or cream-colored face skin. Males are larger, darker, and have a larger patch of bare face skin than females.

According to new research from The Australian National University (ANU), unless conservation efforts are stepped up immediately, one of our most beautiful songbirds, the regent honeyeater, may become extinct within the next 20 years. The new analysis shows that existing, already intensive conservation efforts are insufficient and that a massive redoubling of effort is required to save these birds from extinction.

“The regent honeyeater population has been destroyed by the loss of more than 90% of its preferred woodland habitats,” said ANU main author Professor Rob Heinsohn. “It was once one of the most widespread species, with sightings spanning from Adelaide to Rockhampton. It is now on course to go the way of the dodo.”

There are fewer than 300 regent honeyeaters left today, making it one of our most endangered bird species. Because of habitat degradation, they must compete with larger species for the remaining habitat. The ANU team began a large-scale investigation in 2015 to better understand the fall of the regent honeyeater population, but they discovered that they are an exceedingly challenging bird to observe in the wild. They are nomads who travel large miles in pursuit of nectar. After 6 years of extensive fieldwork, the researchers determined that the birds’ nesting success has decreased due to nest predation by species such as pied currawongs, noisy miners, and possums.

The regent honeyeater population has been destroyed by the loss of more than 90% of its preferred woodland habitats. It was once one of the most widespread species, with sightings spanning from Adelaide to Rockhampton. It is now on course to go the way of the dodo.

Professor Rob Heinsohn

The scientists created population models using all available knowledge in their latest article to anticipate what will happen to the wild population. “Our simulations reveal that existing conservation efforts have provided important life support for regent honeyeaters, but they do not go far enough,” stated co-author Dr. Ross Crates. “We were able to define the three essential conservation priorities required to ensure the birds’ long-term survival.”

To begin, the models predict that nest success rates for both wild and released zoo-bred birds must roughly quadruple. This necessitates the protection of nests against predation. Second, the number of zoo-bred birds released into the Blue Mountains must increase and be sustained for at least the next 20 years, in addition to nest protection. The Taronga Conservation Society has been breeding the birds in captivity and is working hard to increase the number of chicks available for reintroduction into the wild. Third, the models emphasize that the regent honeyeater population can only be maintained and recovered if more habitat is protected and restored.

Regent honeyeaters are beautiful bird, but there are only approximately 300 remaining in the wild, and efforts to rescue the species are ongoing. A captive-breeding effort is currently ongoing, with approximately 60 birds released in the Hunter Valley — the largest release in NSW history.

Breeding takes place primarily between August and January, throughout the southern spring and summer. The breeding season appears to coincide with the blooming of important eucalyptus and mistletoe species. In a cup-shaped nest, two or three eggs are placed. Nest survival and productivity of successful nests in this species have been shown to be low, with nest surveillance indicating significant predation by a variety of avian and arboreal mammal species. There is also a male bias to the adult sex ratio, with an estimated 1.18 males per female.

“We know from modeling that in order to keep this species continuing, we have to release zoo-bred birds into the wild every few years,” Mick Roderick, Birdlife Australia’s NSW woodland bird program manager, said.

“Without more habitat, reintroductions and nest protection initiatives will be worthless,” Professor Heinsohn stated, “since flock sizes will never reach the critical mass required for the birds to breed successfully without our protection.” “Our research offers both promise and a grim warning: we can save these birds, but it will take a lot of effort and resources spread out over a long period of time.”

The study was published in the journal Biological Conservation. Members of the Regent Honeyeater Recovery team, including Birdlife Australia and Taronga Conservation Society, collaborated on the paper.