The distribution of great whales in New Zealand waters will be impacted by climate change, according to recent research. The largest mammal in the planet is the whale. New Zealand is home to almost half of the world’s whale and dolphin species.

Under several climate change scenarios, a multi-university study led by Massey University, the University of Zurich, Canterbury University, and Flinders University projected the regional range shift of blue and sperm whales by the year 2100.

The research, which was published in the prestigious international journal Ecological Indicators, demonstrates a southerly shift of habitat that is suited for both species, which shift’s amplitude increases with ocean warming.

The most extreme climate change scenario tested resulted in a 61% loss and a 42% reduction of the current habitat that is suitable for sperm and blue whales, primarily in New Zealand’s northern waters.

Research lead Dr. Katharina Peters of the University of Canterbury says, “Regardless of which of the climate change scenarios will be the reality, even the best-case scenario indicates notable changes in the distribution of suitable habitat for sperm and blue whales in New Zealand.”

Whales are members of the cetacean family of mammals, which also includes dolphins and porpoises. The larger cetaceans are commonly referred to as whales, and the smaller ones as dolphins.

Some of the animals we refer to as whales, however, actually come from the dolphin family. In New Zealand there are five such whales: the killer whale (orca), short-finned pilot, long-finned pilot, false killer and melon-headed whales.

The whale watch industry off Kaikoura may be at potential risk due to fewer and less reliable sightings of sperm whales off that coastline in the future. Such changes in sperm whale distribution would have socioeconomic impacts due to the direct and indirect reliance on the whale watching activities by the local economy.

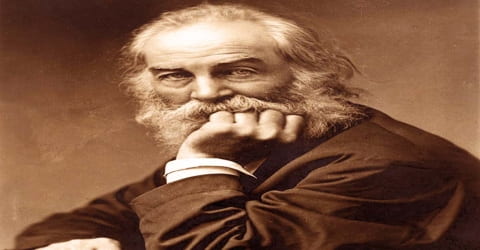

Professor Karen Stockin

Islands like New Zealand are particularly susceptible to the effects of climate change on marine ecosystems due to their close ties to the ocean. For instance, sperm whales in New Zealand are essential to the region’s tourism sector and economy.

Study co-author Professor Karen Stockin, who leads the Cetacean Ecology Research Group at Massey University, says, “The whale watch industry off Kaikoura may be at potential risk due to fewer and less reliable sightings of sperm whales off that coastline in the future. Such changes in sperm whale distribution would have socioeconomic impacts due to the direct and indirect reliance on the whale watching activities by the local economy.”

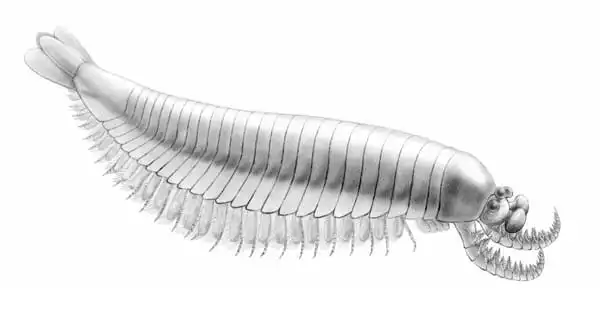

Mammals that live on land gave rise to whales. They eventually evolved into aquatic creatures, yet like all mammals, they continue to breathe air, give birth to live infants, and feed their calves milk. Early baleen whale fossils dating back 35 million years have been discovered in the Waitaki Valley in north Otago, New Zealand.

Blue and sperm whales, among other great whales, are crucial ecosystem engineers. They perform a wide range of duties, including promoting the movement of nutrients from deep waters to the surface and traveling between feeding and calving regions across latitudes.

Their anticipated future southerly shift, brought on by climate change, would affect how ecosystems function and may even destabilize biological processes in New Zealand’s north.

While the detrimental effects of climate change on blue and sperm whales are emphasized in this research, it also highlights potential habitats for both species in the South Island and offshore islands.

Senior author Dr. Frédérik Saltré, co-leader of the Global Ecology Lab at Flinders University says, “Such areas have the potential to serve as climate refugia for both species. Knowing about these areas early on provides an opportunity for their increased protection in the future, particularly when considering the placement of marine protected areas and the legislation of oil and gas exploration.”