According to a major new bioarchaeological study, very few individuals in England ate huge amounts of meat before the Vikings arrived, and there is no evidence that elites ate more meat than others.

Peasants occasionally staged opulent meat feasts for their kings, according to a sister study. The findings challenge long-held beliefs about early medieval English history.

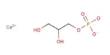

- ‘You are what you eat’ isotopic analysis of over 2,000 skeletons by far the largest of its kind.

- Early medieval diets were far more similar across social groups than previously thought.

- Peasants did not provide food to kings as an oppressive tax; instead, they threw feasts, implying that they were treated with greater respect than previously imagined.

- Surviving food lists are supplies for special feasts not blueprints for everyday elite diets.

- Some feasts served up an estimated 1kg of meat and 4,000 Calories in total, per person.

Royal feasts containing enormous amounts of meat come to mind when you think about medieval England. Historians have long speculated that royals and nobles consumed significantly more meat than the general population and that free peasants were required to give over food to their rulers throughout the year in a system known as feorm, or food-rent.

However, two Cambridge co-authored articles published today in the journal Anglo-Saxon England paint a very different picture, one that has the potential to change our perceptions of early medieval royalty and society.

Bioarchaeologist Sam Leggett presented a talk that piqued historian Tom Lambert’s interest while finishing his Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge (Sidney Sussex College). Dr. Leggett, who is now at the University of Edinburgh, examined the chemical traces of diets preserved in the bones of 2,023 persons buried in England between the fifth and eleventh centuries.

She then compared these isotopic results to indicators of social standing such grave goods, body posture, and grave orientation. Leggett’s research found no link between high protein diets and socioeconomic standing.

The scale and proportions of these food lists strongly suggests that they were provisions for occasional grand feasts, and not general food supplies sustaining royal households on a daily basis. These were not blueprints for everyday elite diets as historians have assumed.

Tom Lambert

Tom Lambert was shocked because several medieval manuscripts and historical studies imply that Anglo-Saxon elites ate a lot of meat. They began collaborating to figure out what was really going on.

They started by reading a food list made during King Ine of Wessex’s reign (c. 688-726) to figure out how much food was recorded and how many calories it contained. They estimated that the supplies totaled 1.24 million kcal, with animal protein accounting for more than half of it.

Because the list comprised 300 bread rolls, the researchers calculated overall quantities based on one bun being served to each diner. 500g mutton, 500g beef, another 500g fish, eel, and poultry, plus cheese, honey, and ale, would have provided each guest with 4,140 calories.

The researchers looked at ten other food lists from southern England and found a strikingly similar pattern: a small amount of bread, a large amount of meat, a reasonable but not excessive amount of ale, and no mention of vegetables (although some probably were served).

Lambert says: “The scale and proportions of these food lists strongly suggests that they were provisions for occasional grand feasts, and not general food supplies sustaining royal households on a daily basis. These were not blueprints for everyday elite diets as historians have assumed.”

“I’ve been to plenty of barbecues where friends have cooked ludicrous amounts of meat so we shouldn’t be too surprised. The guests probably ate the best bits and then leftovers might have been stewed up for later.”

Leggett says: “I’ve found no evidence of people eating anything like this much animal protein on a regular basis. If they were, we would find isotopic evidence of excess protein and signs of diseases like gout from the bones. But we’re just not finding that.”

“The isotopic evidence suggests that diets in this period were much more similar across social groups than we’ve been led to believe. We should imagine a wide range of people livening up bread with small quantities of meat and cheese, or eating pottages of leeks and whole grains with a little meat thrown in.”

Even royals, according to the study, would have eaten a cereal-based diet and considered these infrequent feasts a treat.

Peasants feeding kings

These feasts would have been extravagant outdoor affairs, with whole bulls being grilled in massive pits, as evidenced by excavations in East Anglia.

Lambert says: “Historians generally assume that medieval feasts were exclusively for elites. But these food lists show that even if you allow for huge appetites, 300 or more people must have attended. That means that a lot of ordinary farmers must have been there, and this has big political implications.”

Raedwald, the early seventh-century East Anglian monarch possibly buried at Sutton Hoo, is said to have received food renders from the free peasants of his kingdoms, known in Old English as feorm or food-rent.

It is commonly considered that these were the principal source of food for royal households, with the king’s own holdings serving as a secondary supply. As kingdoms grew larger, it was supposed royal gifts redirected that food rent to support a larger elite, increasing their power over time.

However, Lambert examined the word feorm in other contexts, including aristocratic wills, and concluded that it referred to a single feast rather than this rudimentary tax.

This is significant since food rent required no personal engagement from a king or lord, as well as no acknowledgment of the peasants who were obligated to supply it. The dynamics would have been considerably different if monarchs and lords had attended common feasts in person.

Lambert says: “We’re looking at kings traveling to massive barbecues hosted by free peasants, people who owned their own farms and sometimes slaves to work on them. You could compare it to a modern presidential campaign dinner in the US. This was a crucial form of political engagement.”

This reconsideration has the potential to have far-reaching ramifications for medieval studies and English political history in general. Food renders have influenced theories about the origins of English kingship and land-based patronage politics, and they remain at the heart of ongoing discussions about how England’s once-free peasantry came to be enslaved.

Leggett and Lambert are currently waiting for isotopic data from the Winchester Mortuary Chests, which are believed to contain the remains of Egbert, Canute, and other Anglo-Saxon royals. These findings should provide unprecedented insight into the eating patterns of the period’s most powerful people.