Poliomyelitis (Polio)

Definition: Poliomyelitis, also known as polio and infantile paralysis, is a highly contagious viral infection that can lead to paralysis, breathing problems, or even death. In about 0.5 percent of cases, there is muscle weakness resulting in an inability to move. This can occur over a few hours to a few days. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1 in 200 polio infections will result in permanent paralysis.

Polio can be classified as occurring with or without symptoms. About 95 percent of all cases are asymptomatic, and between 4 and 8 percent of cases are symptomatic.

Poliovirus can be transmitted through direct contact with someone infected with the virus or, less commonly, through contaminated food and water. People carrying the poliovirus can spread the virus for weeks in their feces. People who have the virus but don’t have symptoms can pass the virus to others.

Here are some key points about polio –

- Polio is caused by the poliovirus.

- The vast majority of polio infections present no symptoms.

- Polio has been eradicated in every country of the world except for Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

- Pregnant women are more susceptible to polio.

- Around half of the people who have had polio go on to develop post-polio syndrome.

Polio mainly affects children younger than 5. However, anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated is at risk of developing the disease. Paralytic polio can lead to temporary or permanent muscle paralysis, disability, bone deformities, and death.

The disease may be diagnosed by finding the virus in the feces or detecting antibodies against it in the blood. The disease only occurs naturally in humans. The disease is preventable with the polio vaccine; however, multiple doses are required for it to be effective.

Polio Vaccine: Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio. Both types induce immunity to polio, efficiently blocking person-to-person transmission of wild poliovirus, thereby protecting both individual vaccine recipients and the wider community (so-called herd immunity).

There are two vaccines available to fight polio:

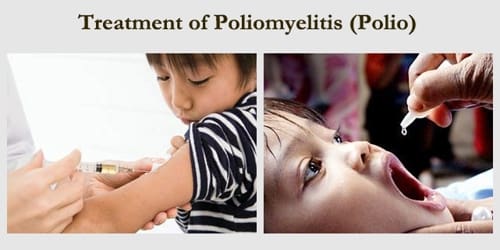

- Inactivated poliovirus (IPV) – IPV consists of a series of injections that start 2 months after birth and continue until the child is 4 to 6 years old. This version of the vaccine is provided to most children in the U.S. The vaccine is made from inactive poliovirus. It is very safe and effective and cannot cause polio.

- Oral polio vaccine (OPV) – OPV is created from a weakened form of poliovirus. This version is the vaccine of choice in many countries because it is low cost, easy to administer, and gives an excellent level of immunity. However, in very rare cases, OPV has been known to revert to a dangerous form of poliovirus, which is able to cause paralysis.

Adults aren’t routinely vaccinated against polio because most are already immune, and the chances of contracting polio are minimal. However, certain adults at high risk of polio who have had a primary vaccination series with either IPV or the oral polio vaccine (OPV) should receive a single booster shot of IPV.

A single booster dose of IPV lasts a lifetime. Adults at risk include those who are traveling to parts of the world where polio still occurs or those who care for people who have polio.

Diagnosis and Treatment: The doctor will diagnose polio by looking at the patient’s symptoms. They’ll perform a physical examination and look for impaired reflexes, back and neck stiffness, or difficulty lifting their head while lying flat.

A laboratory diagnosis is usually made based on recovery of poliovirus from a stool sample or a swab of the pharynx. Antibodies to poliovirus can be diagnostic and are generally detected in the blood of infected patients early in the course of infection. Analysis of the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is collected by a lumbar puncture (“spinal tap”), reveals an increased number of white blood cells (primarily lymphocytes) and a mildly elevated protein level. Detection of virus in the CSF is diagnostic of paralytic polio but rarely occurs.

Because no cure for polio exists, the focus is on increasing comfort, speeding recovery and preventing complications. Supportive treatments include:

- Pain relievers

- Portable ventilators to assist breathing

- Moderate exercise (physical therapy) to prevent deformity and loss of muscle function

Today, many polio survivors with permanent respiratory paralysis use modern jacket-type negative-pressure ventilators worn over the chest and abdomen. Other historical treatments for polio include hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, massage, and passive motion exercises, and surgical treatments, such as tendon lengthening and nerve grafting.

Prevention: The best way to prevent polio is to get the vaccination.

However, other methods of limiting the spread of this potentially fatal disease include:

- avoiding food or beverages that may have been contaminated by a person with poliovirus

- checking with a medical professional that your vaccinations are current

- being sure to receive any required booster doses of the vaccine

- washing your hands frequently

- using hand sanitizer when soap is not available

- making sure you only touch the eyes, nose, or mouth with clean hands

- covering the mouth while sneezing or coughing

- avoiding close contact with people who are sick, including kissing, hugging, and sharing utensils

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends polio vaccination boosters for travelers and those who live in countries where the disease is occurring. Once infected there is no specific treatment. Be sure to receive a vaccination before traveling to an area that is prone to polio breakouts.

Information Source: