A WEHI study could help to address a long-standing mystery: why does a vital immunological organ in our body shrink and lose function as we age? The thymus is an important organ for optimum health because it produces immune cells that fight infections and cancer.

In a world-first, researchers discovered novel cells that drive this aging process in the thymus – crucial findings that could lead to a technique to restore thymus function and prevent our immunity from diminishing as we age.

At a glance

- The thymus is an organ essential for our immune defence but it shrinks and weakens as we get older. The reason for this loss remains a long-standing mystery.

- A new study has been able to visualise, for the first time, how two cell types drive this ageing process and cause the thymus to lose its function and regeneration abilities over time.

- The findings could help uncover a way to stop the thymus from ageing and, critically, develop methods to restore immunity in vulnerable people in the future.

Our discovery provides a new angle for thymic regeneration and immune restoration, could unravel a way to boost immune function in vulnerable patients in the future.

Prof Gray

T cells, commonly known as T lymphocytes, are white blood cells that play an important function in the immune system. T cells are responsible for recognizing and responding to pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, as well as removing contaminated or malignant cells.

The thymus is a small, yet powerful, organ located beneath the breastbone. It is the only organ in the body that produces T lymphocytes. The thymus, however, is the first organ in our body to diminish as we age. As a result, the T cell development regions in the thymus are replaced with fatty tissue, resulting in decreased T cell production and a compromised immune system.

While the thymus is capable of regenerating from damage, to date researchers have been unable to figure out how to unlock this ability and boost immunity in humans as we age. WEHI Laboratory Head Professor Daniel Gray said the new findings, published in Nature Immunology, could help solve this mystery that has stumped researchers for decades.

“The number of new T cells produced in the body significantly declines after puberty, irrespective of how fit you are. By age 65, the thymus has virtually retired,” Prof Gray said.

“As we age, the thymus weakens, making it more difficult for the body to fight new infections, malignancies, and manage immunity. This is also why adults with weakened immune systems, such as those resulting from cancer therapy or stem cell transplants, recover significantly slower than children. These people require years to recover their T cells, and often never do, putting them at a heightened risk of catching potentially fatal infections for the rest of their lives.”

“Exploring ways to restore thymic function is critical to finding new therapies that can improve outcomes for these vulnerable patients and find a way to ensure a healthy level of T cells are produced throughout our lives.”

The new study, an international collaboration with groups at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center (Seattle) and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (NYC), provides crucial new insights that could help achieve this goal.

“Our discovery provides a new angle for thymic regeneration and immune restoration, could unravel a way to boost immune function in vulnerable patients in the future,” Prof Gray said.

Scarring effects

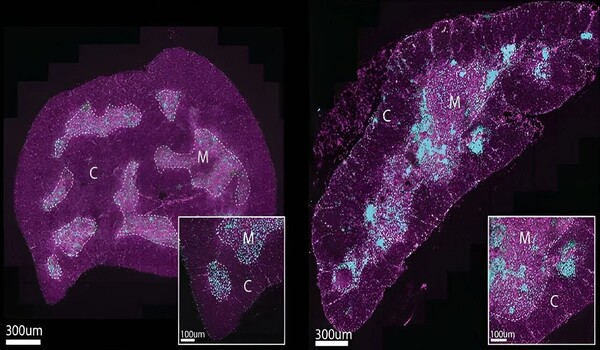

Using advanced imaging techniques at WEHI’s Centre for Dynamic Imaging and animal models, the research team discovered two new cell types that cause the thymus to lose its function. These cells, which appeared only in the defective thymus of older mice and humans, were found to form clusters around T cell growth areas, impairing the organ’s ability to make these important immune cells. In a world-first, the researchers discovered these clusters also formed ‘scars’ in the thymus which prevented the organ from restoring itself after damage.

Dr. Kelin Zhao, who led the imaging efforts, stated that the results revealed for the first time how this scarring process functions as a barrier to thymic regeneration and function. “While a large focus of research into thymic loss of function has focused on the shrinking process, we’ve proven that changes that occur inside the organ also impact its ability to function with age,” Dr. Zhao claimed.

“By capturing these cell clusters in the act and showing how they contribute to loss of thymic function, we’ve been able to do something no one else has ever done before, largely thanks to the incredible advanced imaging platforms we have at WEHI. This knowledge enables us to investigate whether these cells can be therapeutically targeted in future, to help turn back the clock on the ageing thymus and boost T cell function in humans as we get older. This is the goal our team is working towards.”