When and why does type 1 diabetes manifest in children? For the first time, researchers studied newborns and young children who had a higher genetic risk of developing type 1 diabetes over an extended period of time. The results have now been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Diabetes type 1 is a chronic illness also referred to as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes. The pancreas produces little or no insulin in this situation. Our cells cannot operate without insulin because the glucose is kept from entering. Food-derived glucose consequently builds up in the circulation. Blood sugar levels increase as a result of too much stored glucose, which ultimately results in symptoms.

The POInT study is uniquely poised to study blood sugar levels during the development of autoimmunity

Within the framework of the Global Platform for the Prevention of Autoimmune Diabetes (GPPAD), the clinical primary prevention study POInT (Primary Oral Insulin Trial) is conducted multicentrically at seven clinical sites in five countries. POInT aims to prevent the formation of islet autoantibodies, and thus the induction of type 1 diabetes.

People with type 1 diabetes lose their pancreatic beta cells, which produce insulin, due to an immunological response that is misdirected. It was once believed that the pancreatic beta cells are damaged by the autoimmune process and that metabolic alterations take place just before clinical illness manifests.

Nobody had, however, really examined what transpires when the autoimmunity first begins. As a result, the POInT trial followed up often with over 1,000 kids who had a 10% genetic risk of developing type 1 diabetes in the first four months of life, commencing at age four. The time of islet autoantibody formation might then be precisely correlated with changes in blood glucose levels.

The dynamic changes in glucose metabolism in the first years of life were a surprise to us. They very likely reflect changes in the pancreatic islets and signal that we need to study glucose metabolism and the pancreas in early life more intensely.

Katharina Warncke

“Our results change our understanding of the development of type 1 diabetes. We show that metabolic changes occur in an earlier phase of the disease than previously anticipated,” explains Anette-Gabriele Ziegler, Director at the Helmholtz Munich Institute of Diabetes Research (IDF).

Together with an international team of researchers, she conducted the POInT study. The researchers looked at the children’s pre and post-prandial blood sugar levels as well as their islet autoantibodies.

Results provide new approaches for research

First, the findings demonstrated that blood sugar levels soon after delivery are not steady, contrary to the presumption. Instead, they fall during the first year of life before rising once more at about 1.5 years old.

“The dynamic changes in glucose metabolism in the first years of life were a surprise to us. They very likely reflect changes in the pancreatic islets and signal that we need to study glucose metabolism and the pancreas in early life more intensely,” says Katharina Warncke, Chief Physician for Paediatric Endocrinology / Diabetology at the Department of Pediatrics and scientist at the IDF.

Importantly, the researchers discovered that blood sugar levels after meals were greater two months prior to the development of islet antibodies in children who acquired autoimmunity compared to those who did not. Following the treatment, pre-meal levels increased and this difference maintained.

Puzzle around the key event inducing the autoimmune reaction

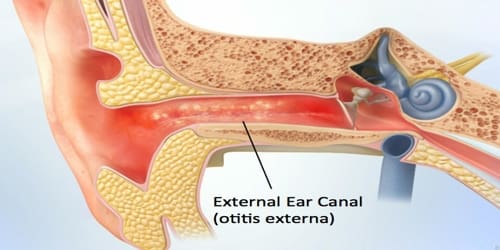

The blood sugar levels of infants and young children exhibit dynamic behavior and reflect the concentration peak of islet autoantibodies, according to the researchers, which denotes a stage of activity and susceptibility of the islet cells.

“The change in post-meal blood sugar levels shortly before the initial detection of autoantibodies points to the likelihood that there is an event impairing the function of the islets preceding and contributing to the autoimmune reaction. As glucose values further increase after seroconversion, the impairment or damage seems to be sustained leading to further glucose instability,” explains Warncke.

“The observed changes in blood sugar levels in relation to autoantibody formation are exciting. Now we know that the start of the disease process is likely to be acting at the pancreatic islets and we can focus our research to find the cause of this chronic illness,” says Ezio Bonifacio, Professor at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden at the Technische Universität Dresden.

In conclusion, the researchers found that metabolic changes might happen concurrently with or even before autoimmunity, which is a far earlier stage of the disease than previously thought. The researchers hypothesize that a change in islet cell activity is related to the excessive rise in blood sugar levels after eating and just before the production of antibodies.

The goal: prevention of new cases

“Changes in glucose levels could thus serve as an indicator of islet cell dysfunction and a potential onset of autoimmunity against beta cells in the future,” summarizes Ziegler.

However, this necessitates extensive additional research on early childhood biomarkers and glucose metabolism. In the end, researchers hope to lower the number of new instances of type 1 diabetes. Four out of every 1,000 children in Western, industrialized nations are currently affected.