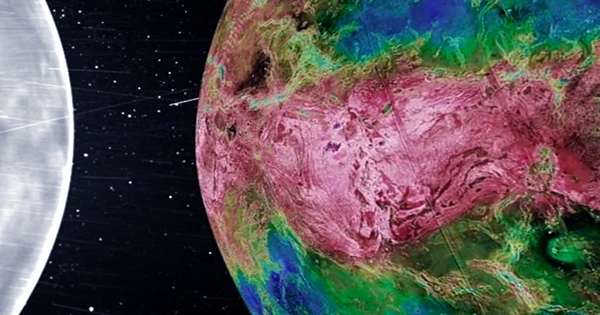

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has obtained the first visible-light photographs of Venus’s surface, demonstrating how the planet’s rocky innards glows red hot. The Evening Star’s surface had never been seen with optical equipment before, hidden beneath a thick layer of unbroken cloud, and scientists expect to learn about Venus’ geology and development by analyzing the probe’s photographs. The Parker Solar Probe is on a mission to study the Sun, and it has made a series of flybys of Venus in order to use the planet’s gravitational field to enhance its trajectory towards our star.

NASA scientists report in a new study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters that the probe’s Wide-Field Imager (WISPR) “unexpectedly penetrated [Venus’] thick atmosphere, detecting thermal emission from the surface” on two of those flybys, which took place in July 2020 and February 2021. “Venus is the third brightest object in the sky, but we haven’t got much knowledge on what it looks like on the surface until recently since our view of it is obstructed by a thick atmosphere,” research author Brian Wood said in a statement. “Now, for the first time from space, we can view the surface in visible wavelengths.”

While the probe’s imaging software was designed to detect aspects of the solar atmosphere, NASA scientists thought they might be able to utilize WISPR to examine Venus’ clouds as Parker went past. The probe’s orbit happened to line up in such a way on the fourth flyby on February 20, 2021, that the imager was able to record the entire nightside of Venus before transmitting the photographs back to Earth. Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that surface features could be seen peering through the planet’s usually dense clouds.

Although most visible light wavelengths are unable to permeate the planet’s thick atmosphere, the study authors state that some of the planet’s longest visible wavelengths are capable of passing through on the planet’s nightside. “Even at night, the surface of Venus is roughly 860 degrees [F, 460°C],” Wood added. “It’s so hot on Venus that the stony surface glows like a piece of iron plucked from a forge.”

The light from these glowing surface features is lost in the intense sunlight reflected off the clouds on the planet’s dayside, but WISPR was able to record the glow radiating from the planet’s super-hot surface on the planet’s nightside. The researchers were able to discern between characteristics like the continental region Aphrodite Terra, the Tellus Regio plateau, and the Aino Planitia plains because higher altitude parts are slightly cooler than lowland ones. The study authors add, “The WISPR images also indicate a brilliant rim of emission near the limb, corresponding with nightglow emission from molecular oxygen, somewhat akin to auroral emissions reported on Earth.”

“There have actually been several reports of feeble emission from the Venusian night side from trustworthy amateur and professional astronomers, dating back to the 1600s,” they go on to say. Scientists had disregarded the so-called “ashen light” phenomena as an optical illusion because it had never been successfully imaged. The photographs from the Parker Solar Probe show that the planet does, in fact, have a noticeable nightside glow, and they allow astronomers to learn more about the planet’s crust composition.

Scientists may be able to identify the minerals there and glean information as to how the planet became such an inferno by analysing the wavelengths of this surface glow, for example. During the probe’s upcoming Venus flybys, the last of which is scheduled for November 2024, more observations will be made.