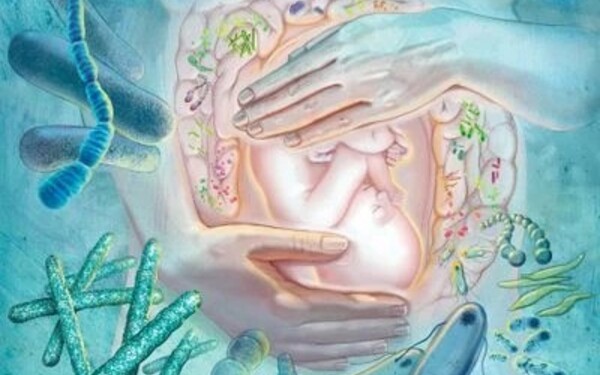

A study on mice discovered that the bacteria Bifidobacterium breve in the mother’s intestines during pregnancy promotes good brain development in the fetus. Researchers compared fetal brain development in mice whose mothers had no bacteria in their gut to those whose mothers received Bifidobacterium breve orally during pregnancy but had no other bacteria in their stomach.

Nutrient transfer to the brain increased in fetuses of women who received Bifidobacterium breve, and positive alterations were also observed in other cell processes related to growth. Bifidobacterium breve is a ‘good bacteria’ found naturally in our stomach and available as a supplement in probiotic drinks and tablets.

Obesity and prolonged stress can change pregnant women’s gut microbiomes, often leading to baby development problems. Up to 10% of first-time mothers’ newborns are born with low birth weight or fetal growth restriction. If a kid does not develop properly in the womb, he or she is more likely to have conditions such as cerebral palsy as an infant, as well as anxiety, depression, autism, and schizophrenia later in life.

Our study suggests that by providing ‘good bacteria’ to the mother we could improve the growth and development of her baby while she’s pregnant. This means future treatments for fetal growth restriction could potentially focus on altering the gut microbiome through probiotics, rather than offering pharmaceutical treatments – with the risk of side effects – to pregnant women.

Dr Jorge Lopez-Tello

These findings imply that consuming Bifidobacterium breve supplements while pregnant can help improve fetal development, specifically fetal brain metabolism, and hence support the formation of a healthy infant.

The findings were published in the journal Molecular Metabolism.

“Our study suggests that by providing ‘good bacteria’ to the mother we could improve the growth and development of her baby while she’s pregnant,” said Dr Jorge Lopez-Tello, a researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Trophoblast Research, first author of the report.

He added: “This means future treatments for fetal growth restriction could potentially focus on altering the gut microbiome through probiotics, rather than offering pharmaceutical treatments — with the risk of side effects — to pregnant women.”

“The design of therapies for fetal growth restriction are focused on improving blood flow pathways in the mother, but our results suggest we’ve been thinking about this the wrong way — perhaps we should be more focused on improving maternal gut health,” said Professor Amanda Sferruzzi-Perri, a researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Trophoblast Research and senior author of the report, who is also a Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge.

She added: “We know that good gut health — determined by the types of microbes in the gut — helps the body to absorb nutrients and protect against infections and diseases.”

The study was conducted in mice, allowing the effects of Bifidobacterium breve to be studied in a way that would not be conceivable in humans: the researchers were able to precisely regulate the mouse’s genetics, other microbes, and environment. However, scientists suggest the impacts they saw are likely to be comparable in humans.

They now intend to do additional research to track offspring brain development after delivery and to better understand how Bifidobacterium breve interacts with other gut bacteria found in natural environments. Previous research by the same team discovered that giving pregnant mice Bifidobacterium breve improves the structure and function of the placental. This also allows for a greater delivery of glucose and other nutrients to the growing fetus, which promotes fetal growth.

“Although further research is needed to understand how these effects translate to humans, this exciting discovery may pave the way for future clinical studies that explore the critical role of the maternal microbiome in supporting healthy brain development before birth,” said Professor Lindsay Hall at the University of Birmingham, who was also involved in the research.

While it is well known that the health of a pregnant mother is important for a healthy baby, the effect of her gut bacteria on the baby’s development has received little attention.