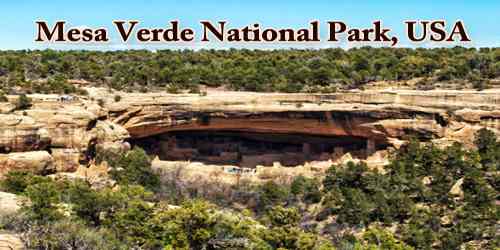

Mesa Verde National Park is an American national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978, which is located in southwestern Colorado, U.S., established in 1906 to preserve notable prehistoric cliff dwellings. The park protects some of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites in the United States.

Occupying a high tableland area of 81 square miles (210 square km), it contains hundreds of pueblo (Indian village) ruins up to 13 centuries old. The most striking are multistoried apartments built under overhanging cliffs. Besides the ruins, the park has some spectacular and rugged scenery. Mesa Verde’s canyons were created by streams that eroded the hard sandstone that covers the area. This resulted in Mesa Verde National Park elevations ranging from about 6,000 to 8,572 feet (1,829 to 2,613 m), the highest elevation at Park Point. The terrain in the park is now a transition zone between the low desert plateaus and the Rocky Mountains.

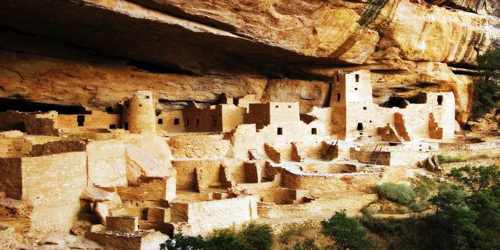

Established by Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the park occupies 52,485 acres (21,240 ha) near the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. With more than 5,000 sites, including 600 cliff dwellings, it is the largest archaeological preserve in the United States. Mesa Verde (Spanish for “green table”) is best known for structures such as Cliff Palace, thought to be the largest cliff dwelling in North America.

The park occupies part of a large sandstone plateau rising more than 8,500 feet (2,600 meters) above sea level that slopes gently to the south. Stream erosion during the past two million years cut deep canyons into the plateau, leaving narrow strips of high tableland, or mesa, between the canyons. Water erosion formed niches and alcoves of various sizes in the sandstone of these canyon walls (where the cliff dwellings are located). On top of these mesas there are windblown deposits of fertile reddish soil (loess). The climate is semiarid and, according to the examination of tree rings, has changed little during the past 600 years. The area’s plant life is adapted to the semiarid climate: piñon-juniper forest is the dominant vegetation on the mesas, and sagebrush is the characteristic vegetation on the canyon floors. Elk are the most common large animals, and there are a few bears and mountain lions and many smaller mammals in the park. Snakes and lizards also abound, as do birds.

The park also offers visitors 8,500 acres of federally designated wilderness that support a wide variety of animal species, including 74 species of mammals, 200 species of birds, 16 species of reptiles, five species of amphibians, six species of fishes and over 1,000 species of insects and other invertebrates.

The Ancestral Puebloans inhabited this area of what is now Colorado for hundreds of years, living on top of the plateau between the 6th and 12th centuries and then in the cliff dwellings until the late 13th century. The drive up to the site is along a gently twisting road to the top of the mesa, where you can tour the sites on the plateau by car to see pit houses and other ruins, and enjoy stunning views of the dwellings in the canyon walls.

About 550 CE, Basketmaker peoples, direct ancestors of the region’s later Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) peoples, moved into the Mesa Verde area. They made pottery and built clusters of semi-subterranean pit houses on the mesa tops at an elevation of 7,000 feet (2,000 metres), where they also cultivated corn (maize), beans, and squash. There was usually sufficient rainfall for their crops, and springs and seeps provided drinking water. About 750 CE, surface dwellings began to be constructed, consisting of houses with vertical walls and flat roofs, all joined together in long rows; archaeologists designate this as the Pueblo I period. Sandstone began to be more commonly used in house construction, and one or more subterranean pit rooms (kivas), probably used for ceremonial purposes, were dug in front of these row houses. Houses with more than one story and round towers also began to be built.

Mesa Verdean farmers increasingly relied on masonry reservoirs during the Pueblo II Era. During the 11th century, they built check dams and terraces near drainages and slopes in an effort to conserve soil and runoff. These fields offset the danger of crop failures in the larger dryland fields. By the mid-10th and early 11th centuries, protokivas had evolved into smaller circular structures called kivas, which were usually 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) across. These Mesa Verde-style kivas included a feature from earlier times called a sipapu, which is a hole dug in the north of the chamber and symbolizes the Ancestral Puebloan’s place of emergence from the underworld. At this time, Mesa Verdeans began to move away from the post and mud jacal-style buildings that marked the Pueblo I Period toward masonry construction, which had been utilized in the region as early as 700 but was not widespread until the 11th and 12th centuries.

Between 1150 and 1200 the Ancestral Pueblo peoples shifted their dwelling sites from the mesa tops into the alcoves in the canyon walls, where they began to build the cliff houses, with rooms averaging 6 by 8 feet (1.8 by 2.4 metres) in size, using sandstone and the construction methods developed earlier. Crops continued to be cultivated on the mesa tops; dry-farming techniques were used. The alcoves under the canyon rims that face south-southwest were preferred for cliff dwellings, probably because of the warming effect of winter sunshine. The largest cliff dwelling in the park is Cliff Palace, which housed as many as 250 people in its 217 rooms and 23 kivas. Long House, the second largest cliff dwelling, has 150 rooms and 21 kivas, where some 150 people lived. However, of the approximately 600 cliff dwellings in the park, most have only one to five rooms each. The population of Mesa Verde probably peaked at about 5,000 persons.

Many other archaeological sites, such as pit-house settlements and masonry-walled villages of varying size and complexity, are distributed over the mesas. Non-habitation sites include farming terraces and check dams, field houses, reservoirs and ditches, shrines and ceremonial features, as well as rock art. Mesa Verde represents a significant and living link between the Puebloan Peoples’ past and their present way of life.

Evidence of violence and cannibalism has been documented in the central Mesa Verde region. By 1285, following a period of social and environmental instability driven by a series of severe and prolonged droughts, they abandoned the area and moved south to locations in Arizona and New Mexico, including Rio Chama, Pajarito Plateau, and Santa Fe. The archaeological record indicates that, rather than being isolated to the Mesa Verde region, violent conflict was widespread in North America during the late 13th and early 14th centuries, and was likely exacerbated by global climate changes that negatively affected food supplies throughout the continent.

By 1300, following the Great Drought (1276-99), most of the people had left Mesa Verde, moving south, according to archaeological evidence, into what is now New Mexico and Arizona. These people are among the ancestors of the present-day Pueblo Indians. Several of the cliff dwellings, including Cliff Palace, are open to visitors; camping is available, and a lodge is open in the park in the summer.

Within the boundaries of the property are located all the elements necessary to understand and express the Outstanding Universal Value of Mesa Verde National Park, including habitation and non-habitation archaeological sites and features, as well as settlement patterns. Excavated sites have been stabilized and undergo routine monitoring, condition assessment, and preservation treatment, based on continuing research and consultation. The property is of sufficient size to adequately ensure the complete representation of the features and processes that convey the property’s significance and does not suffer from adverse effects of development and/or neglect. There is no buffer zone for the property.

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mesa Verde National Park has a Warm Summer Humid continental climate (Dfb). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters at 6952 ft (2119 m) elevation is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -0.1 °F (-17.8 °C). The region’s precipitation pattern is bimodal, meaning agriculture is sustained through snowfall during winter and autumn and rainfall during spring and summer. Water for farming and consumption was provided by summer rains, winter snowfall, and seeps and springs in and near the Mesa Verde villages.

At 7,000 feet (2,100 m), the middle mesa areas were typically ten degrees Fahrenheit (5.5 °C) cooler than the mesa top, which reduced the amount of water needed for farming. The cliff dwellings were built to take advantage of solar energy. The angle of the sun in winter warmed the masonry of the cliff dwellings, warm breezes blew from the valley, and the air was ten to twenty degrees warmer in the canyon alcoves than on the top of the mesa. In the summer, with the sun high overhead, much of the village was protected from direct sunlight in the high cliff dwellings.

Mesa Verde National Park is authentic in terms of its forms and designs, materials and substance, location and setting, and spirit. Large portions of the sandstone and mud-mortar multi-storey buildings have survived intact in form and materials, a tribute to the engineering skills of these early peoples as well as the dry environment of the mesa’s alcoves. These architectural remains reflect the range of ancient Pueblo construction techniques as well as settlement patterns. Extensive research on both the structures and many artifacts has provided a wealth of information about the lifestyles of the former occupants.

In 1966, as with all historical areas administered by the National Park Service, Mesa Verde was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1987, the Mesa Verde Administrative District was listed on the register. It was designated a World Heritage Site in 1978. In its 2015 travel awards, Sunset magazine named Mesa Verde National Park “the best cultural attraction” in the Western United States.

Information Sources: